The first print on 1Q22 real GDP growth released today showed a -1.4% annualized rate of decline. Like others, we had been looking for a slight growth rate of around 1% until March foreign trade data were released yesterday, showing a huge increase in the trade deficit in March. On the “strength” of that data, we revised our 1Q forecast to -0.7%; the actual number came in still lower.

Wall Street analysts have blamed the decline on the foreign trade swing, and this was indeed a big part of the picture. What we haven’t heard elsewhere as yet is that consumer spending also disappointed substantially, with total real consumer spending showing only a 1.8% rate of growth, compared to Street forecasts in the 3% to 4% range. Within that total, spending on goods actually declined, which accounted for most or all of the consumption shortfall.

No, the consumer is not dropping off the table. However, the 1Q declines in goods consumption continue the trend we have discussed for some time. Spending on goods has been flat for the last year, with paltry increases in one quarter offset by similarly paltry declines in other quarters. Consumers are widely touted as spending freely on merchandise, but that description has not been apt for over a year. Since then, spending has been shifting from goods to services, and the latter is still depressed relative to pre-Covid trends. Overall real consumer spending is growing right on or slightly below pre-Covid trends, hardly the excess demand story some are telling.

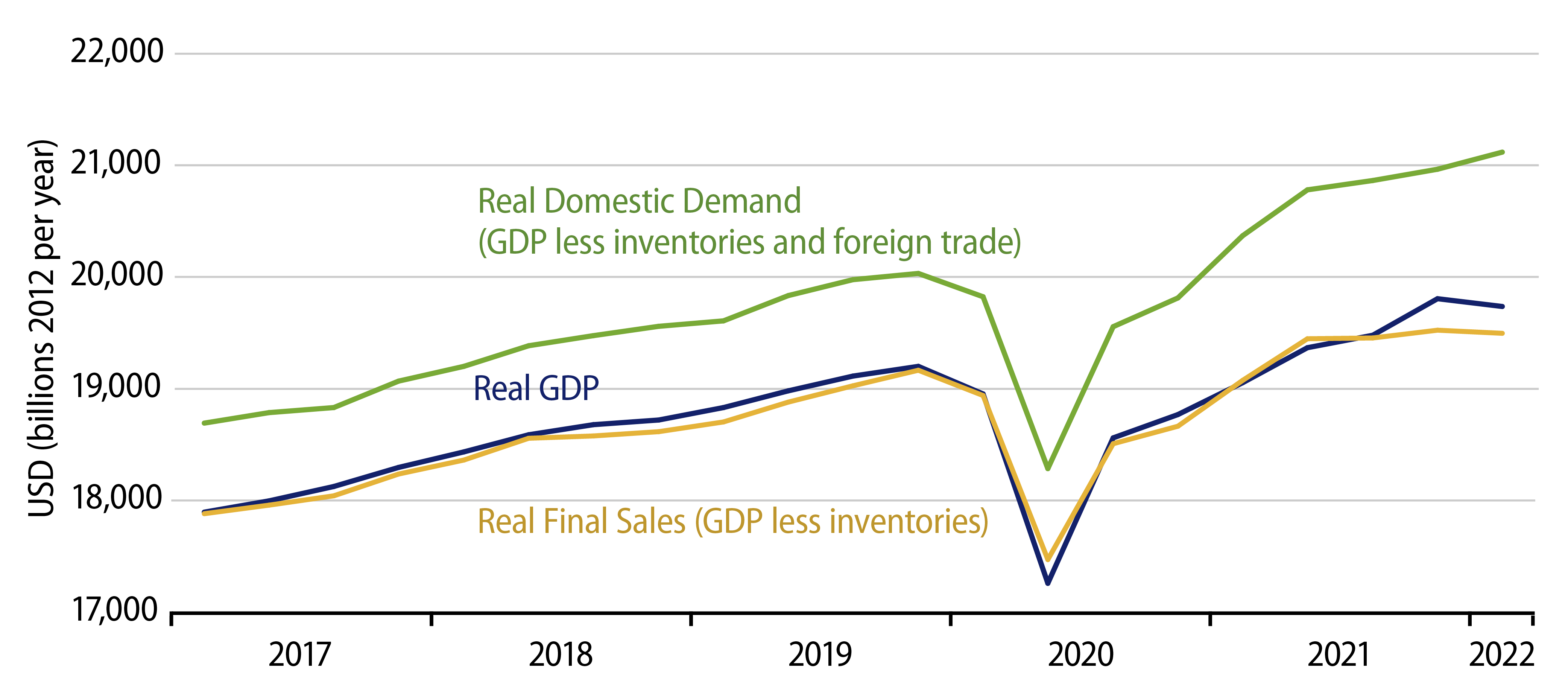

As for GDP, no, the economy is not dropping into recession, at least not presently. With the distortions from foreign trade, the 1Q print is an understatement of “true” growth in the quarter. By the same token, however, the 4Q GDP growth rate of 6.9% was vastly overstated by extremely sharp increases in inventories and only a slight deterioration in the trade balance.

Imports and inventories of goods have both been rising dramatically in recent months, and this rise reflects two sides of the same phenomenon, as supply constraints are easing and the supply of goods is catching up with demand. In a perfect world with perfect data, the increases in inventories and imports would exactly offset each other, with little or no net impact on GDP. In the world of imperfect data in which we actually live, reported inventories were much stronger than imports in 4Q, while the reverse was true in 1Q.

Average 4Q and 1Q together, and GDP has grown at a 2.7% rate over the last six months, about the same rate as seen in 3Q, before all the inventory/import kerfuffle. This is a good description of “underlying” growth rates at present. Whether the Fed’s latest turn to hawkishness and the markets’ response to that drive still-lower growth is now becoming the question at hand.