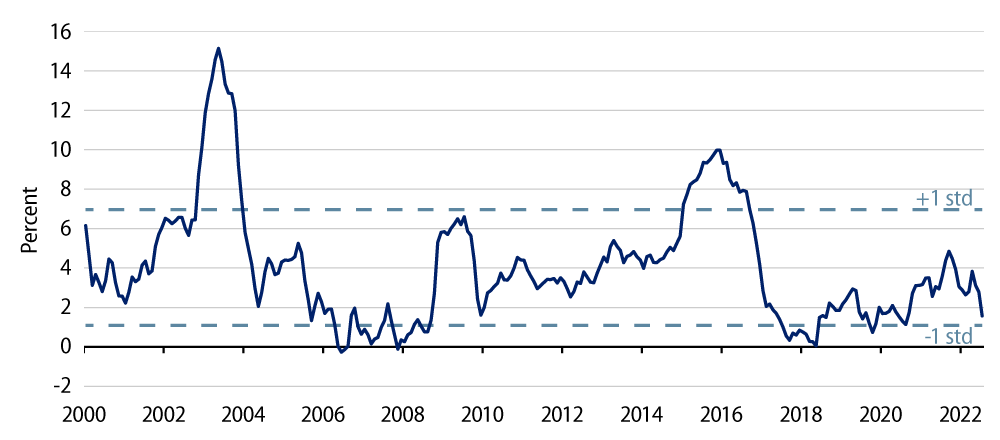

Back in 1Q21, Brazil’s Central Bank (BCB) became the first monetary authority to reverse the uber-loose (Exhibit 1) policy that had prevailed during the pandemic era, starting to move it to a significant contractionary stance. At that time, BCB not only recognized that the so-called transitory supply shocks were not so transitory, but also became vocal in saying that there was a component related to global demand that would put pressure on inflation in the short term. By March 2021, BCB started to hike the overnight rate, moving rates from 2.0% to 2.75%. One and a half years later, we now see rates at 13.75%. After such aggressive moves, we believe that BCB has ended the tightening cycle despite the current inflation and inflation expectations are still trailing above the inflation target ceiling. Most likely, rates will be kept “on hold” until mid-2Q23.

Brazil has a long history of high and persistent inflation that usually forces the central bank to rapidly react to shocks whenever they occur, and that was what drove BCB to reverse the monetary stimulus much earlier than any other major central bank. Additionally, it was very clear that the Brazilian authorities had, at the time, a different assessment of the economic scenario (that proved to be correct as time went on), which has also played an important role in this process. BCB perceived that global demand was running well above supply and that it would lead to rising and persistent inflation in the medium term, which would translate into higher domestic inflation. Initially, BCB assumed that it would have to just reverse the excess of monetary stimulus, but soon recognized that it would have to move to contractionary territory to curb current inflation and keep inflation expectations under control. Adding insult to injury, the Russia-Ukraine war materialized and presented an unexpected adverse shock on an already very high CPI, forcing BCB to extend the tightening cycle further to control rising inflation expectations.

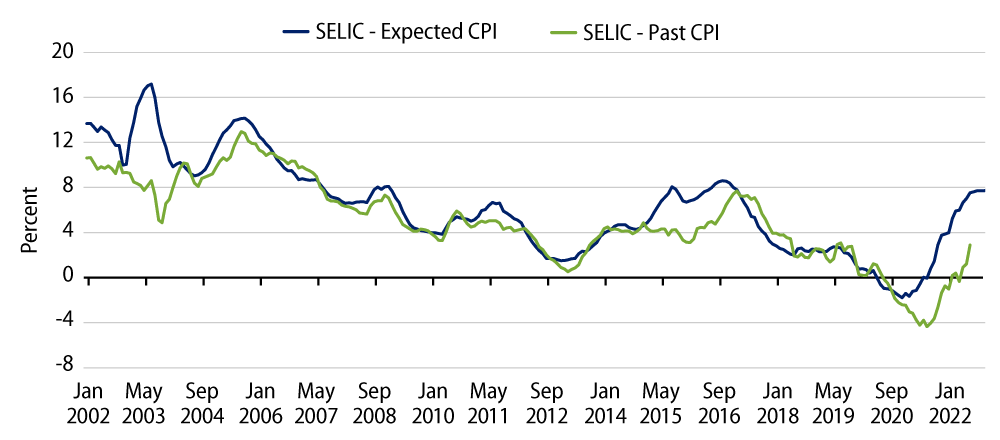

Looking ahead, we anticipate some moderation in growth for 2H22, at 1.7%, on a seasonally adjusted annual rate (saar) basis, down from 4.2% in 1H22, and a contraction in 1H23. This contraction is a consequence of the maintenance of rates at very restrictive level for some time. Our Monetary Condition Index (Exhibit 2) shows loose monetary conditions until 1Q22, shifting to contractionary territory in 2Q22, tightening further in 2H22 and remaining at this level for most of 2023.

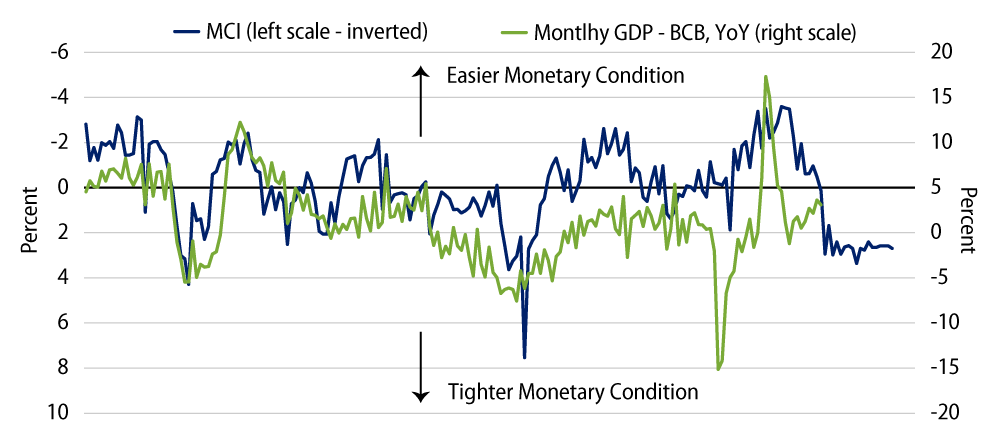

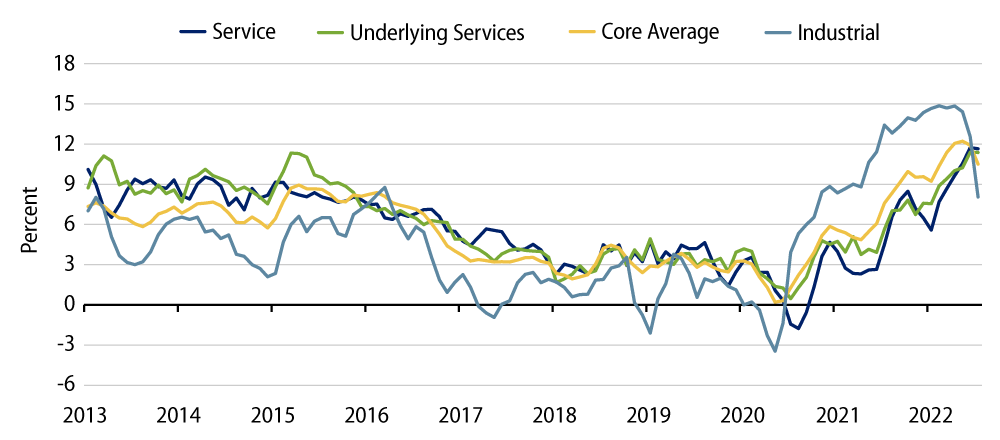

As mentioned earlier, even though we expect BCB to “pause” the tightening cycle now, we do not anticipate any cut in rates until 2Q23, because inflation is still high and above the inflation target. CPI has moderated in July and August on the back of lower taxation on gas, telecom and electricity; however, core inflation did not decelerate and service inflation continues to move up (Exhibit 3). We foresee IPCA, the Extended national Consumer Price Index, at 6.2% year-over-year (YoY) in December, well below the recent peak of 12.1% in June 2022. However, bringing IPCA back to the target will demand a sharper contraction on service inflation, which depends on a lower growth rate and a higher unemployment rate.

All in, BCB has correctly read the global inflationary shock, which together with the lagged effect of the uber-loose monetary and fiscal policies in response to the pandemic pushed Brazil’s CPI to its recent highs, and began to reduce its monetary stimulus efforts prior to those of other central banks. However, new shocks, such as the Chinese supply chain disruption (2H21) and the Russia-Ukraine war (2Q22) have pushed inflation even higher, forcing BCB to tighten more and to communicate a “high for longer” guidance regarding policy rates to push inflation back down to its target.

Even though a large portion of current inflation could be attributed to a global adverse scenario (Exhibit 4), we believe BCB has the tools to bring inflation back to its target in the monetary policy horizon (2024), even if this leads to a mild recession in Brazil in 2023.