China’s bond market has been making headlines lately due to the high-profile credit woes of a few highly leveraged property developers such as Evergrande and Fantasia. Western Asset’s Desmond Soon, Portfolio Manager and Head of Investment Management, Asia (ex-Japan), and Jie Peng, Research Analyst, answer questions about the latest developments regarding the credit woes of high-yield developers in China, its impact on the rest of the Chinese economy, the strength of the yuan, power shortages and high-quality China bonds.

What is the fallout resulting from the credit woes of high-yield property developers such as Evergrande on China’s economy?

Concerns over the viability of a highly leveraged Chinese property developer Evergrande have escalated since the beginning of September. The rapid deterioration of the developer’s credit woes and increasing fears of potential contagion have sent shockwaves through the Chinese property sector, impacting China homebuilders’ equities and bonds. This development is occurring amid a cyclical soft patch in China’s growth cycle in the third quarter and a likely acceleration in the implementation of property taxes in pilot cities, sparking fears of a significant decline in China’s property sector and the Chinese economy overall. Some analysts expect the Evergrande situation to be China’s “Lehman moment”—a comparison with the US investment bank’s collapse that precipitated the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2008. While we believe that a shakeup of China’s property homebuilders will have a meaningful supply-chain impact on China’s economy, we believe that the fallout will be contained, manageable and real estate prices in China and China’s overall economy will remain resilient for the following reasons:

First, the real estate development industry in China is highly fragmented and geographically dispersed, in stark contrast to the dominance of a handful of players in the case of Hong Kong. The top 10 property companies in China account for just about one-quarter of the market share, compared with roughly half in developed market (DM) countries. For example, Evergrande accounts for 4.5% of China’s homebuilders market on a contracted sales basis.

Second, unlike the “no questions asked, no money down” subprime mortgages that were dished out prior to the GFC, the loan-to-value (LTV) ratio of mortgage loans made to Chinese homebuyers is very conservative at 50%-60% LTV, with significant homebuyer equity and banks having full recourse to the borrower. Further, the financial nexus from the “zero-down” subprime mortgages that were repackaged into complex financial derivatives (e.g., CDOs and CDO2) and distributed to global investors prior to the GFC is not present in the China situation.

Third, Chinese banks, which are mostly state-owned are generally prohibited from lending to property developers for land purchases (their main expenditure). Hence, Chinese developers fund their land bank acquisitions via issuing domestic bonds/wealth management products and tapping the offshore USD-denominated Asia bond market (China homebuilders constitute 50% of the JP Morgan Asia Credit High Yield Index). Hence, even in the case of Evergrande, the Chinese banking system’s exposure is about 0.1% of the country’s total banking system assets and slightly over 5.0% of the total banking system’s bad debt reserves. From the perspective of Chinese policymakers, letting some highly leveraged homebuilders like Evergrande fail in an orderly fashion may allow the authorities to exercise more control over the housing market, by facilitating the consolidation of its better-capitalized competitors through taking up its market share.

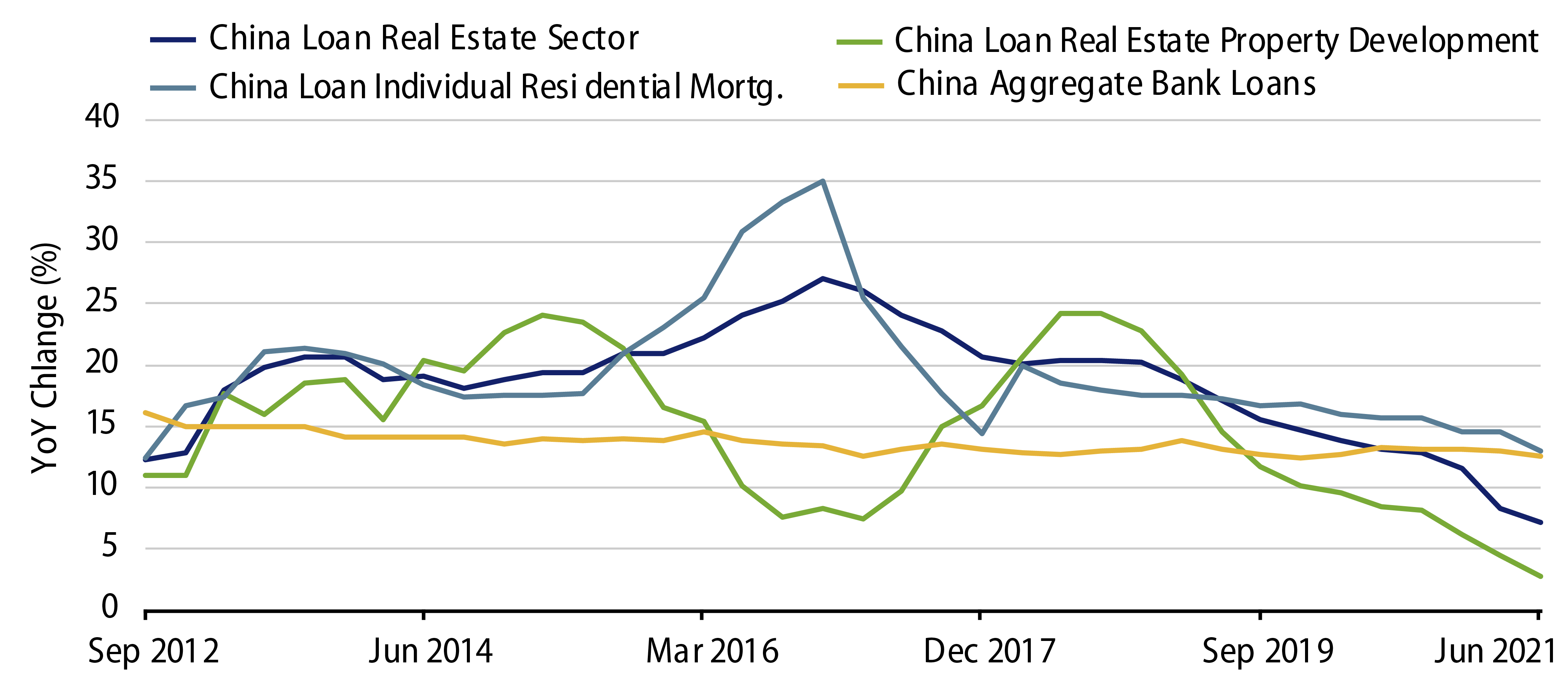

That said, the key risk for the Chinese economy stems not from the collapse of a few highly indebted homebuilders such as Evergrande and Fantasia, but from a drastic tightening of lending/loans for the entire sector (Exhibit 1). This would significantly impact its long economic supply chain (e.g., construction companies, subcontractors, steel makers, etc.). In this regard, we believe that the Chinese authorities are highly cognizant of the fallout risk and have macro levers to pull should there be a need for countercyclical measures. These measures could include additional cuts to the bank reserve requirement to spur lending to the property sector and an easing of the policy rate. State-owned Chinese banks can be directed to extend credit to homebuyers and to shorten approved mortgage disbursement wait times to help ease cash flow pressures at the developers. The upshot of our assessment is that the ability and willingness of Chinese policymakers to navigate the vagaries of GDP growth is strong.

On the growth outlook, activity should rebound from the current soft patch to post a full-year GDP expansion of about 8% in 2021, a decent outcome in the context of the COVID-19 challenges. We expect the authorities to remain committed to achieving a stable growth path over the long term.

What about the sharp fall in Chinese stock prices following the regulatory crackdown across a wide range of sectors?

The Chinese government’s recent regulatory tightening covered a wide range of sectors such as after-school tutoring, fintech, e-commerce and online gaming.

We have seen a sharp selloff in Chinese equities listed in the US and Hong Kong stock exchanges on the back of the regulatory crackdown. For context, the Hang Seng Tech Index, which contains the largest tech stocks from China, is down over 20% year to date (YTD). Chinese education stocks listed in the US are down over 90% YTD. However, we do not believe that recent regulatory moves will have a material impact on the Chinese economy in the near term. Stocks from the new economy sectors, which are in the crosshairs of the regulatory crackdown, are mainly listed in the US and Hong Kong stock exchanges with a small representation in the onshore A-share market. Hence, the onshore Shanghai A-Share Composite is little impacted, and in fact up 3% YTD. Furthermore, the wealth effect from a decline of the stock market in China has historically not been meaningful as equity holdings accounted for less than 20% of Chinese households’ net assets. In the domestic bond/wealth management product markets, Chinese new technology and school tutoring companies have issued very few bonds and wealth management products (WMPs). As a result, domestic investors largely are not impacted by the regulatory crackdown.

What is your view on the recent power shortage in China and its impact?

The recent power shortage in China reflected a supply/demand imbalance driven by a rapid increase of power consumption due to strong export demand, tight supply of thermal coal and surging coal prices, alongside a lack of incentives for Chinese power generators to increase capacity as power tariffs are regulated and low. The Chinese central government’s target to lower energy intensity and carbon emissions under the dual-control policy also played a role.

China’s power sector has a heavy reliance on coal-fired power, which accounts for 65% of its overall power generation. In tackling the situation, the government has requested local coal mines to ramp up production, and is seeking to boost coal imports. The government is also encouraging power generators to sign long-term contracts with suppliers to ensure supplies heading into the winter peak season. Furthermore, to improve power generators’ ability to pass through higher coal costs, in October the authorities announced they would allow the prices of coal-fired electricity to rise by as much as 20% above the government-set benchmark, compared with the previous 10% cap. This should incentivise power generators to increase power generation. Thus, we expect the power shortage to be eased to some degree in the coming months due to the slew of policy measures. In the medium to longer run, as part of the government’s green initiatives, we think the Chinese government will continue focusing on boosting supply of renewable power and power storage infrastructure, and reduce the country’s reliance on coal-fired power.

In terms of implications, first, the energy crunch is temporary and is expected to reduce China 2021 GDP by 0.6% with the most severe impact felt in 4Q21. Importantly, the recent energy crunch is not confined to China. Globally, Covid-impacted supply bottlenecks and the rapid push for clean and renewable energy has unleashed the unintended consequence of raising prices and creating shortages in traditional energy sources like oil, gas and coal (heavily used by China’s power plants and steel mills). In fact, natural gas, the low-emission key transitionary fossil fuel has seen its price more than double in Europe. With the global reopening of economies and the onset of winter, we are likely to see the impact of rising energy prices spread to DM economies such as Japan, the EU and the US.

Second, we have observed that China’s Producer Price Index (PPI), which represents factory gate prices, has risen sharply this year while its Consumer Price Index (CPI) has remained benign. China’s CPI comprises 20% food prices including a significant portion in pork prices, where the supply of hogs has been successfully micro-managed by the Chinese authorities. However, we have to be watchful of how long this unusual situation can persist and its impact on factory profit margins. Besides the domestic impact, we should also be very thoughtful of the global impact of rising China factory prices. Given China’s position as the world manufacturing centre and recovering global demand, Chinese manufacturers should be able to pass on their input price increases globally.

Why is the Chinese yuan so strong amid the negative news?

Some analysts have argued that the Chinese yuan (CNY) has not priced in slowing Chinese growth and the selloff seen in Chinese equity and USD China high-yield credits. In our view, the resilience of the CNY is simply the result of China’s strong balance of payments position offsetting growth differentials and offshore investors selling Chinese equities.

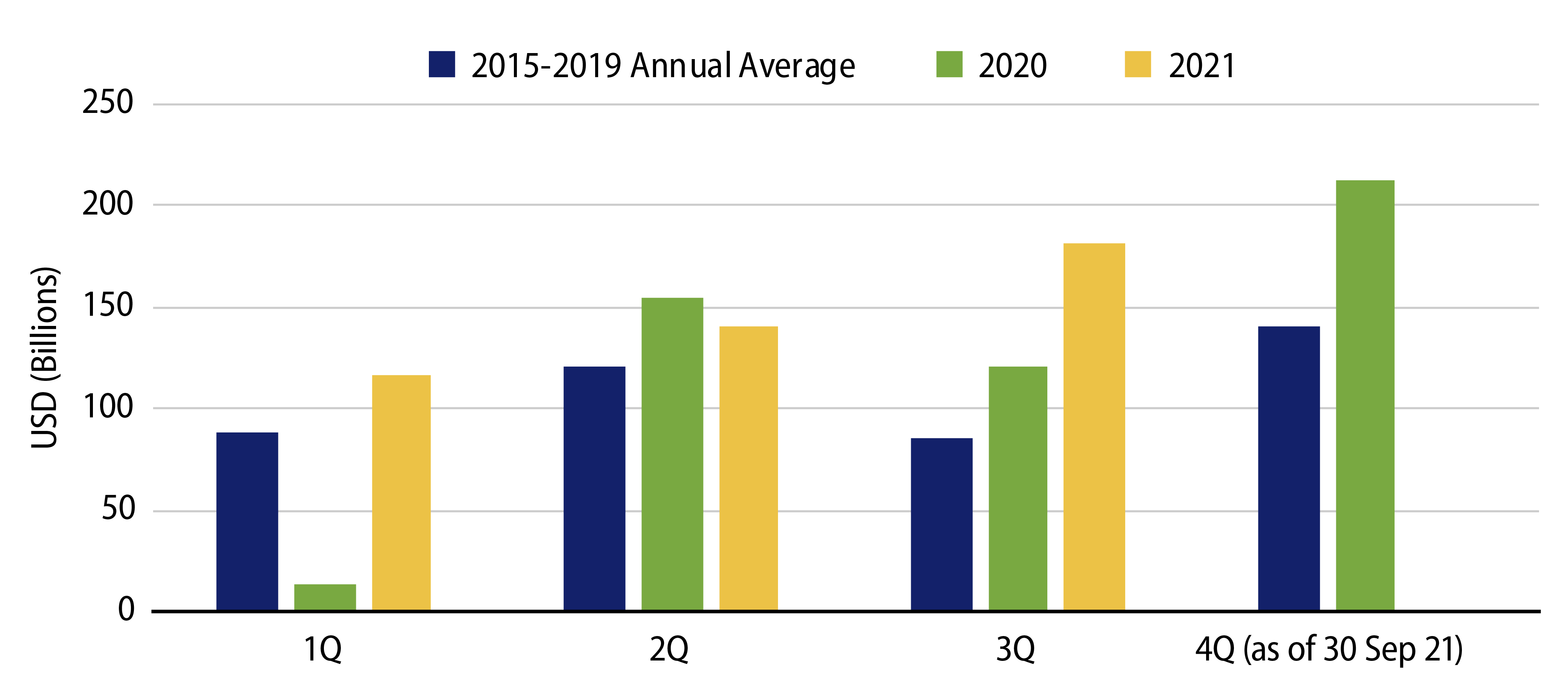

First, China’s trade surplus is strong and the services deficit is small. The trade surplus in 2021 is even stronger than 2020 when China exported medical and IT equipment to the rest of the world which was crippled by the Covid pandemic. The current run rate for China’s trade surplus is higher than it was in 2020 and higher than the 2015-2019 average (Exhibit 2). Seasonally, China’s trade surplus tends to be strong in 4Q due to the Western holiday season and FX conversion of exporters/corporates is at historical ratio of 60%. With little foreign currency loan demand, the stock of US dollars deposits held by exporters and corporates in China’s onshore banking system has risen to an estimated $1 trillion.

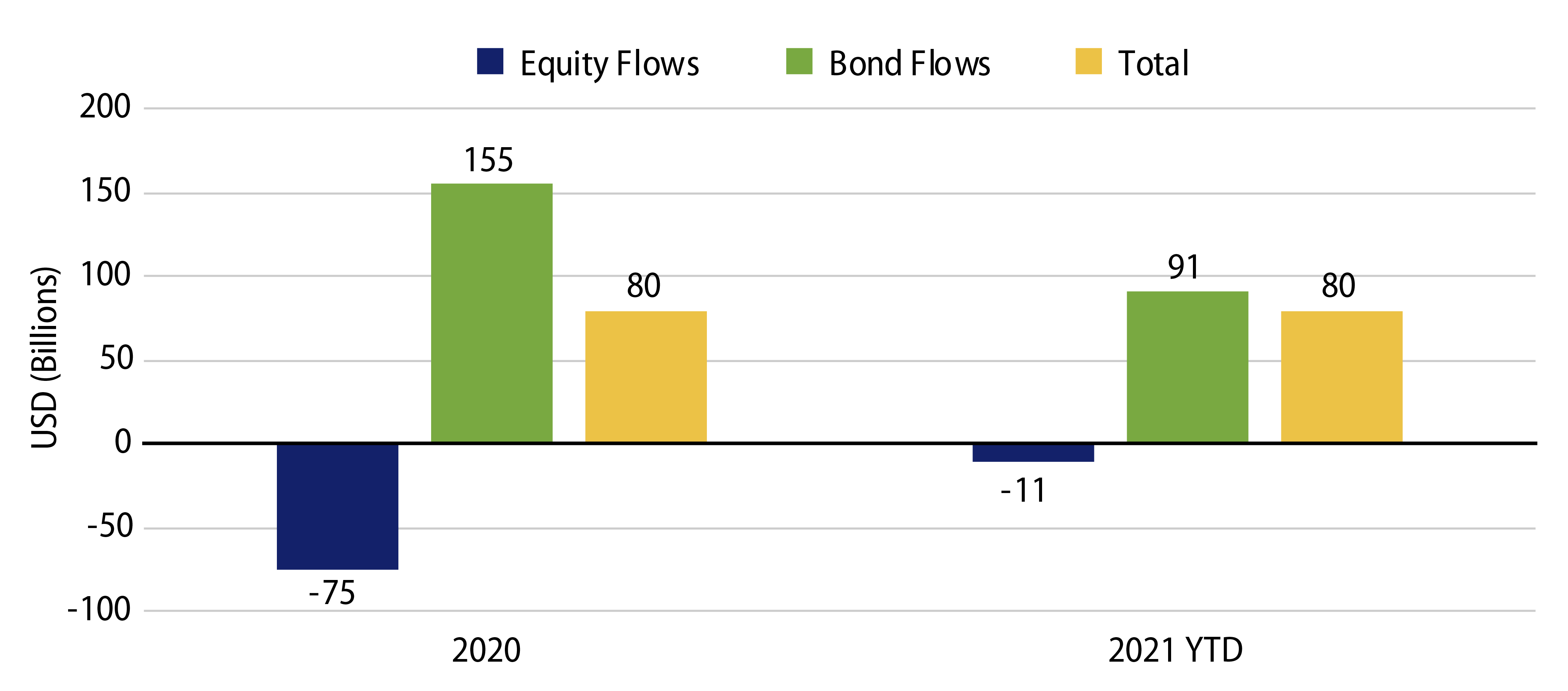

Second, since the onset of the pandemic, China’s capital outflow picture has changed dramatically. International travel, a traditional conduit for capital outflows and offshore M&A activities, has virtually ceased (Exhibit 3). This, coupled with the strong trade balance and portfolio flows into onshore Chinese government and quasi-government bonds due to major bond index inclusion, has largely offset foreign selling of Chinese equities, driving the CNY stronger despite a slew of negative news (Exhibit 4). That said, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) is unlikely to allow a large unmanaged appreciation of the CNY trade basket from current 100 levels (the strongest in the last five years) and we expect measures to slow its rise (e.g., further opening up of South-Bound Bond Connect and increases in QDII quotas). However, with strong external accounts and foreigners already significantly underweight Chinese equities, we expect that the CNY will be resilient and likely to continue to outperform most emerging market (EM) FX.

How have the Chinese high-quality bonds such as Chinese government, quasi-government and USD-denominated China investment-grade bonds performed this year?

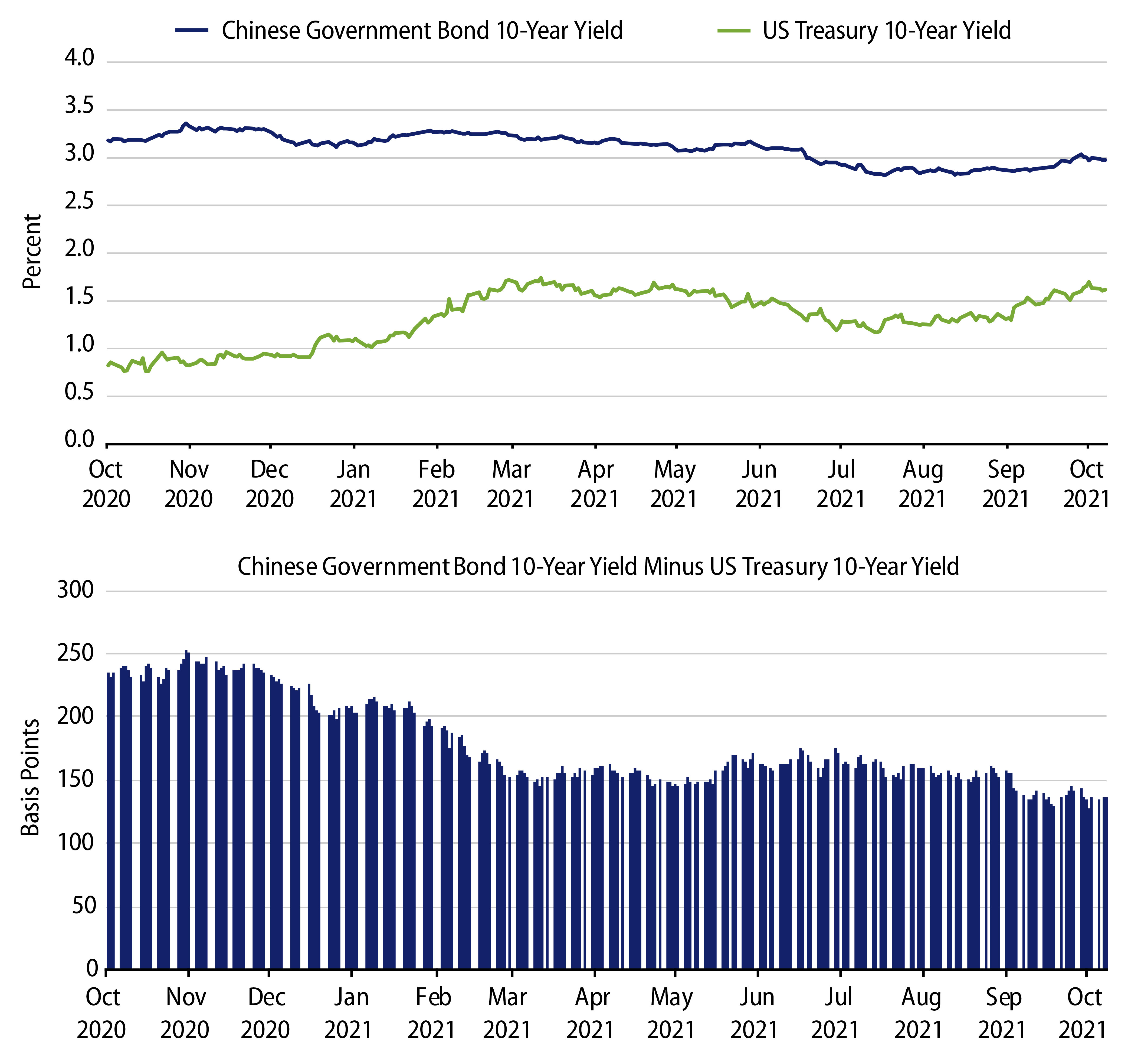

High-quality Chinese bonds have continued to perform well this year with onshore Chinese government bond (CGB) and quasi-government bond yields declining for much of 2021, and decoupling from the selloff in DM bonds due to reflation fears in 1H2021. Offshore USD-denominated Chinese investment-grade bonds have also seen credit spreads tighten despite the China Huarong problem and the turmoil in high-yield property developer bonds.

We think onshore 10-year CGBs will remain range-bound between 2.8% and 3.2%. The expected increase of local government (LG) bond issuance due to weaker land sales will likely lead to a modest rebound in CGBs and LG bond yields in 4Q21. However, we believe the rise in yields will not be significant or sustained, due to the accommodative monetary policy stance amid downward pressure on growth. Offshore USD-denominated China investment-grade funds continue to receive modest retail inflows on the back of captive technical support from large USD deposits in China and Hong Kong. We advocate for investors to conduct due diligence and credit research to avoid idiosyncratic issuer risk.