It has been a busy two days, with the Commerce Department providing benchmark revisions to GDP, personal income and consumer spending data covering the last five years or so, with these data rebased from a 2012 to a 2017 base year, and with new data on August consumption and Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) inflation announced today.

Net of the rebasing, the benchmark revisions to data were not earthshaking. GDP growth is now estimated to be a little slower over the last year than previously estimated and ditto for consumer spending. That is, real GDP is now estimated to have grown 2.4% from 2Q22 to 2Q23, rather than the 2.5% previously estimated, and real consumer spending is now estimated to have grown 2.7% from July 2022 to July 2023, rather than the 3.0% previously estimated.

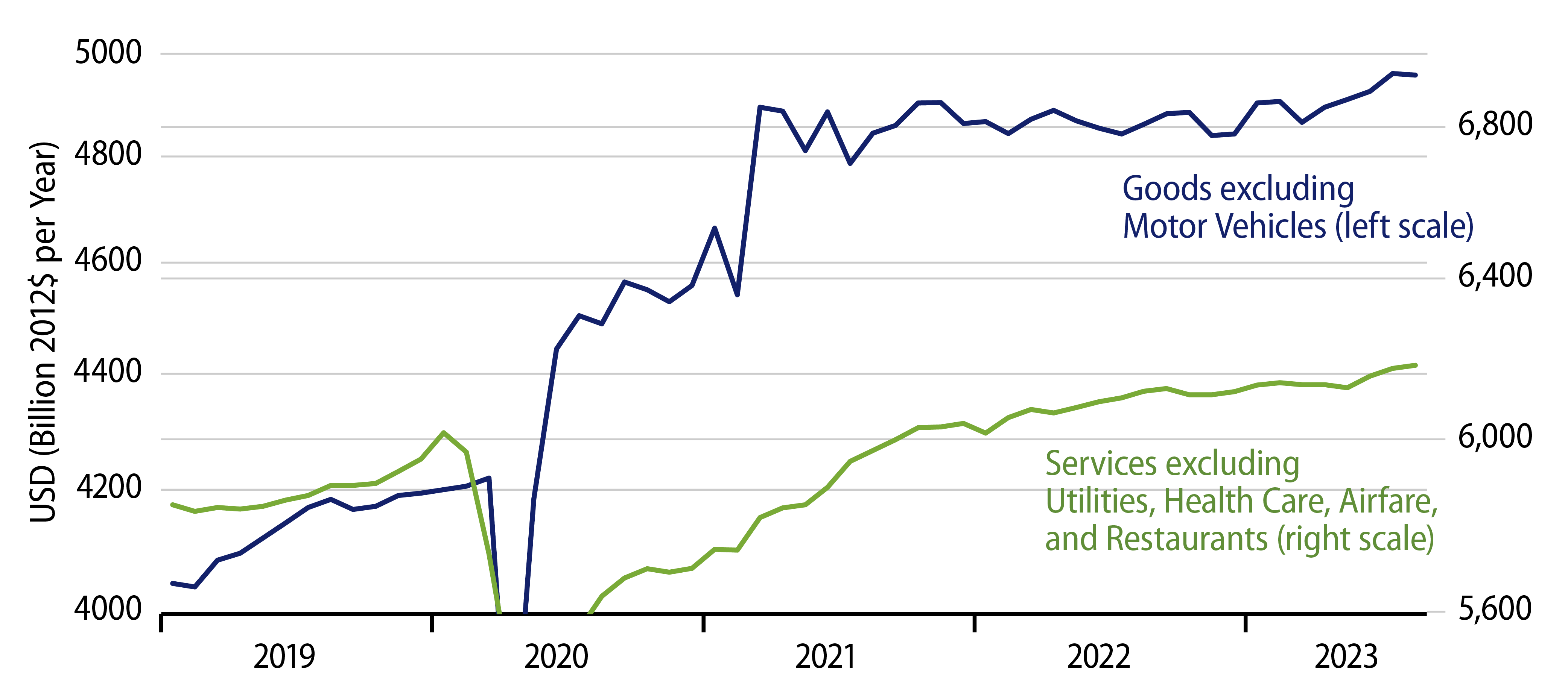

For August developments, real consumer spending is estimated to have grown less than 0.1%, as services spending growth moderated and goods spending declined. Exhibit 1 shows our take on “underlying” trends in consumer spending. As you can see there, goods spending improved noticeably over May-July, before the August decline, and services spending picked up in June and July, before the August moderation.

The improvements through July in these measures comprise the lion’s share of the improvement in the economy that many Wall Street analysts have been touting and that was reflected in the Federal Reserve’s (Fed) latest economic projections. This improvement caught us by surprise, our thinking being that low saving rates, rising interest rates, sinking stock prices and decelerating job growth would restrain consumption.

Maybe the softer spending growth in August is a first sign of consumers coming back into line with our story. Maybe it is a random blip. As usual, we will have to await further data to know for sure.

(As you may have noticed, the goods and services aggregates in Exhibit 1 exclude various components. We do this to provide smoother series, not to hide developments in the excluded components. And, in fact, none of the excluded components participated in the aforementioned May-July spending pickup, so our exclusions do not change the story in favor of our conclusions.)

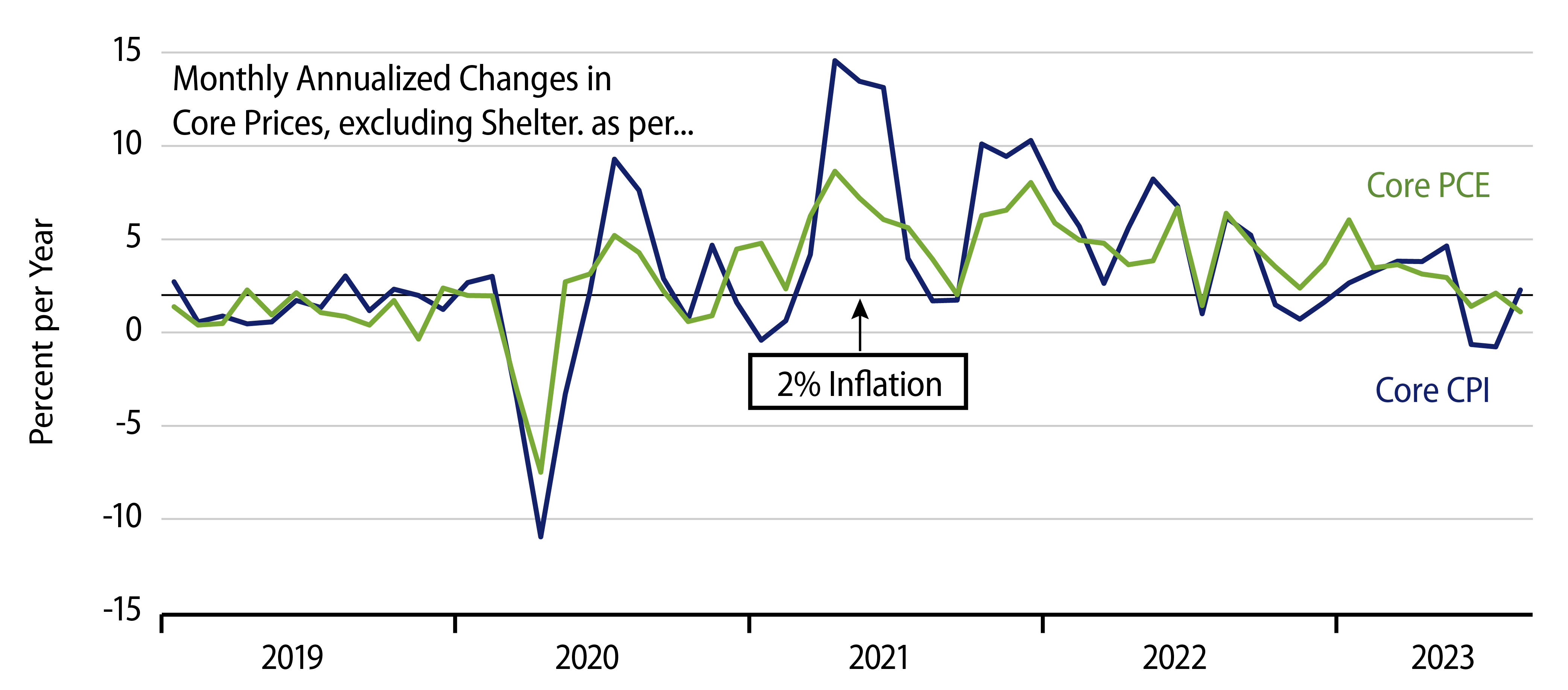

On the inflation front, the news was favorable, at least it was upon looking past the 10.7% rise in gas prices. Excluding food and energy prices, core PCE inflation moderated to a 1.8% annualize rate of increase in August. The Fed has acknowledged that reported shelter prices are still reflecting months-ago realities rather than current market conditions.

Excluding those shelter prices, core PCE inflation was at a 1.1% annualized rate in August. Shelter prices are indeed moderating, and we would assert that the core excluding shelter change cited here is an indicator of where overall core PCE inflation could be headed.

Economists—and the Fed—exclude gas prices from the core measure partly because of their extreme volatility but also partly because they are determined largely outside domestic markets. Yes, high gas prices are hurting American consumers, but should the Fed be hiking policy—piling onto the pain—because of the actions of OPEC and Russia? The general conclusion is no, especially with other prices in the economy starting to behave themselves.

Meanwhile, yes, we are focusing on one-month inflation rates rather than the 12-month inflation rates so popular in the press. As we argue in a forthcoming paper, fixating on 12-month inflation rates tells one what inflation was doing six months ago, not what it is doing now. Yes, one-month inflation rates will have to be sustained at current levels for a few months more to placate the Fed, but that is a different proposition from asserting that current inflation rates need to fall further. Meanwhile, as seen in Exhibit 2, core inflation rates excluding shelter for both the CPI and PCE have been hovering around the Fed’s 2% target for the last three months, so the August data are looking less and less like an aberration and more and more like an emerging trend.

To repeat, we’ll have to sustain recent inflation rates a while longer for the Fed to declare victory over inflation. And a drop in gas prices wouldn’t hurt either. But a careful look at the recent data gives the lie to those asserting that a 2% inflation rate is unattainable.