The latest COVID-19 vaccine trial results have been the most promising by far, but the enormous macro challenges going into 2021 must not be downplayed. The pandemic-induced lockdowns have created unprecedented humanitarian and economic crises for emerging market (EM) and developed market (DM) countries alike. Most governments are rightfully concentrating their efforts on stemming the viral spread. Market expectations are now looking for growth to rebound from this year’s severe contraction, an outcome that is obviously welcome. Nevertheless, careful attention must be given to lasting damage beyond the economic recovery. Of note, budget deficits globally have widened as sharp declines in tax revenues are accompanied by expenditure spikes to mitigate the economic blow to households and corporations.

While policy responses to the pandemic have varied across EM countries, we believe that the coronavirus will weigh heavier on the Latin American region while Asia is expected to fare better. For example, China was successful in arresting its first wave of COVID-19 infections. Further, the low reservoir of active cases, and the use of non-pharmaceutical interventions in China (e.g., intensive testing, contract tracing, quarantine and mobility restrictions) was effective in arresting the second wave of flare-ups as well; this has allowed China’s economic recovery to pick up steam, in turn supporting the Asia region more broadly. This is in contrast to Latin America where the leadership in Mexico and Brazil was not able to contain the virus effectively and where economic activity levels remain depressed.

The key differentiating factor between EM and DM countries is the capacity for debt financing. Despite larger fiscal deficits, DM countries are much better positioned—given ample fiscal space to issue debt in their own currencies—and typically at minimal cost. In addition, their central banks have actively used quantitative easing (QE) programs to facilitate the monetization of government debt. To be sure, the QE tool has been similarly deployed by a handful of EM countries (including Hungary, Indonesia and Poland). But the majority of EM countries would have to rely on sovereign bond issuance as a supplement to official aid programs. In fact, US dollar debt issuance in EM countries so far this year has surpassed the levels seen over the same period in 2019 and 2018. Dominated by higher-rated countries, new debt issues this year have been met with strong investor sponsorship. Indeed, even lower-rated issuers have joined the festivities by issuing debt at historically low yields with lengthened maturities.

Yet at the same time, the pandemic has laid bare EM vulnerabilities. Distressed countries such as Ecuador, Lebanon and Zambia have defaulted on their debt in a bid to alleviate pressure on their fiscal positions. Other weak single-B countries remain on the hook, particularly for those with policymakers unwilling to be subject to the macro discipline tied to International Monetary Fund (IMF) programs. Investment-grade-rated countries have not been spared either as this year’s slew of debt issuance did not go unnoticed by ratings agencies, which have placed numerous EM governments on negative outlook while downgrading others. Low BBB rated sovereigns should take heed of early warning signals by ratings agencies and bond investors alike in order to avoid becoming “fallen angels.”

Still, there are nascent signs of economic healing, most notably in external balances. EM current account deficits have narrowed, and in some instances, turned into surpluses. The pandemic-induced shock in domestic demand has translated into an instantaneous plunge in imports, and was exacerbated further by a depreciation of exchange rates (since foreign goods become more expensive in local currency terms). Although global demand for EM exports has fallen as well, the reduction of imports more than offset the compression of exports, thereby benefiting the trade balance. This improvement cannot be overstated, since it is coming at a time when overseas remittances and tourist receipts—which are important sources of hard currency for many EM countries—are considerably lower for the most part (e.g., Mexico continued seeing strong remittances coming from the US.). As economic normalcy resumes, this positive dynamic sets forth a virtuous cycle of asset price recovery as external funding needs decline.

Indeed, the experience of economic crises in the past decades underscores the resilience of EM countries. In many cases, sovereign fundamentals have improved with structural reforms, enhanced governance and policy prudence. Large EM countries have taken advantage of their rich resources and/or favorable demographics to improve their balance sheets, which now helps them to withstand exogenous shocks such as the pandemic. Most monetary authorities have departed from exchange rate pegs, allowing their currencies to float within acceptable ranges and act as a relief valve during times of stress. Importantly, as local debt markets grow in depth and breadth, many are now included in global benchmarks, thus making them more mainstream and less exotic. There are at least two benefits. The first is the emergence of captive participation by banks, insurers and pensions. The second is reduced risk of currency mismatch between assets and liabilities.

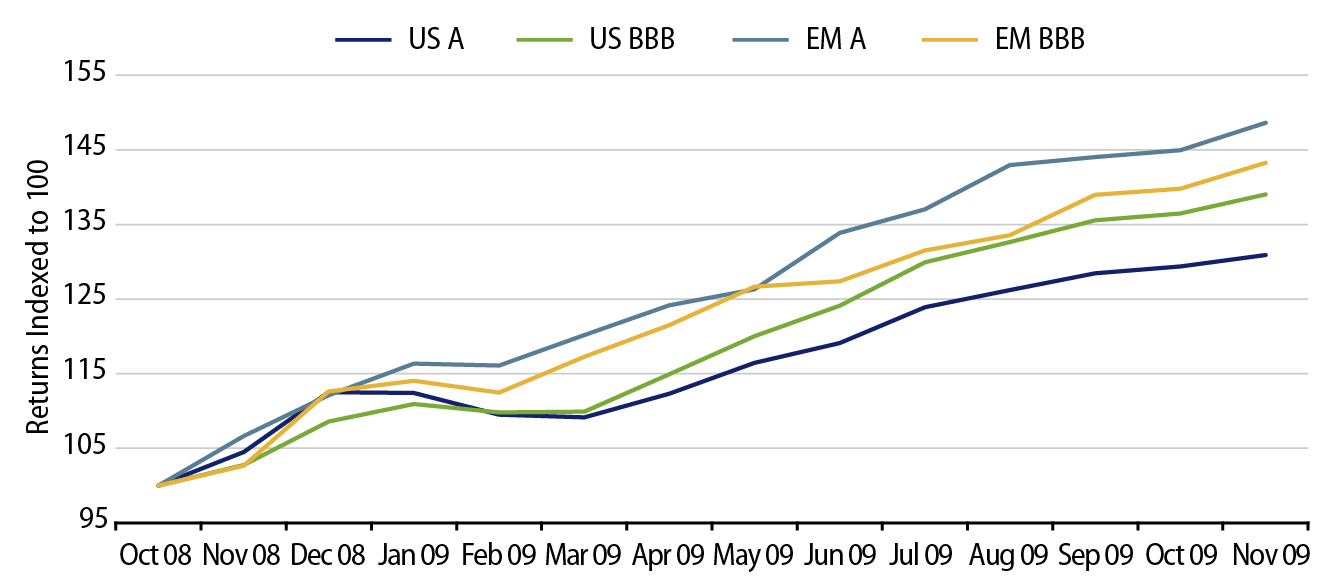

If history serves as a guide, EM performance tends to be strong during periods of global recovery. For example, after the global financial crisis (GFC), EM bond spreads rallied and retraced most of the loss within the subsequent year, with higher-rated bonds generally outperforming. As you can see in Exhibit 2, A rated EM debt securities outperformed during the post-GFC period. In comparison to the current episode, although EM debt has rallied sharply since the depths of the selloff in March 2020, we’re still off the tights of pre-pandemic levels. We therefore see ample room for spread compression and attractive relative returns.

Even assuming a constructive backdrop, the recovery in EM asset prices is likely uneven, if not K-shaped. By definition, EM is a highly heterogeneous asset class. While some countries will emerge from the coronavirus crisis stronger, others may face new challenges ahead on the sociopolitical front, reflecting unpleasant consequences of the pandemic. It is entirely possible that more defaults and restructurings lie ahead. We believe active management with a focus on credit differentiation will be the key to navigating the vagaries of the asset class, even during the best of times. At Western Asset, our investment philosophy for EM continues to be centered on a long-term value discipline, with a strong emphasis on diversified strategies. We believe this is in line with our objective to seek consistent risk-adjusted returns over full market cycles.