Private-sector payrolls rose by 189,000 in March, with the February jobs level revised downward by 32,000. Average workweeks declined by 0.1 hours, so that total hours worked (jobs time hours) declined -0.1% on the month. Finally, average hourly wages rose 0.27%, or at a 3.3% annualized rate.

Mr. Powell and friends have stated they want labor market growth to slow, but they have never professed to want a recession. Well, the labor markets in March were barely above stall speed: anything slower would be recession. If the Fed is serious about not actually wanting a recession, it should be more than satisfied with what we are seeing in the March data, and the same conclusion holds even if you fold in the results for all of the last five months.

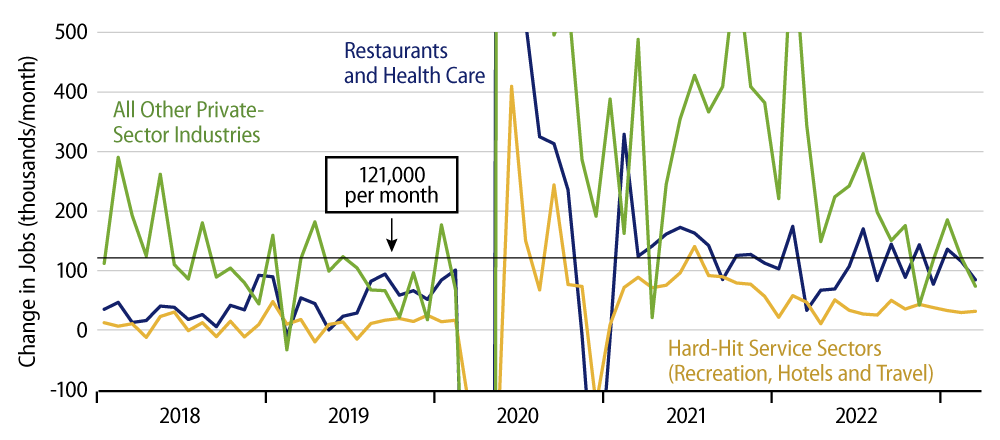

Take the jobs total. As we have stated previously, five service sectors were especially hard hit by the Covid shutdown, and none of those sectors has yet re-attained pre-shutdown jobs levels, let alone pre-Covid growth trends. Well, those sectors accounted for the bulk of the March private-sector gains, 116,000 out of the 189,000 total.

In other industries where recovery from shutdown has been more complete, March jobs gains were only 73,000, and the average gains for the last five months—including that supposedly strong January print—is only 108,000. Both of these rates are below the 121,000 per month pace of gains we were seeing prior to the Covid shutdown. And remember: both economic growth and inflation were stable prior to Covid.

We emphasize private-sector payrolls to reflect what market forces are doing in the economy. However, the fact is that government payrolls also remain quite depressed, 200,000 jobs (1%) below the level seen in late 2019, before the shutdown and before hiring for the 2020 Census commenced. So, while government jobs rose by 47,000 in March, that made only a small dent in the net decline in government employment since Covid.

The recent jobs gains mark ongoing recovery in shutdown-stricken sectors and less-than-normal job growth elsewhere. Meanwhile, when workers were scarce, employers sharply boosted workweeks for the staffers they actually had. As staffing has been addressed, workweeks have pulled back, partially offsetting the jobs gains. Well, in March, that offset was more than total. Again, workweeks declined enough to reduce total hours worked in March. Total hours worked have grown at only a 1.4% annualized rate over the last five months, about equal to what we were seeing prior to Covid.

Ultimately, the Fed looks to wage growth within the payroll data when it gauges signs of inflationary pressure. Here too, recent data have been benign. We’ve mentioned the 3.3% per year rate of growth in hourly wages in March. For the last five months, said growth has averaged 3.9% per year, right in line with what we were seeing in the non-inflationary, pre-Covid economy. Mr. Powell has stated that it is in the service sectors where remaining inflation pressures need to subside. Well, service-sector wages have grown even more slowly, at a 3.6% rate over the last five months.

Granted, these recent rates need to be sustained in order to subdue inflation. However, they have been sustained for the last five months now, and the pace of jobs, workweek and wage gains in recent months suggests further slowing, if anything. Short of recession, it is hard to imagine a more inflation-friendly payroll report than what we saw in March. We’ll see if Powell et al are perspicacious enough to notice.