What’s the difference between emerging markets (EM) and “frontier markets”?

Frontier markets are a subset of EM. There’s not necessarily a uniform definition. They tend to be a mix of countries that are at an earlier stage of economic development, that have lower credit ratings, or that are smaller economically, with shallower and less developed capital markets. It’s a diverse mix of countries with a lot of different “economic archetypes.” But one factor that’s common across frontier market countries is that they tend to fly under the radar to some extent, even within the mainstream EM investor community. And there are typically some nuances, as well, that make them more challenging to analyze—politics tend to matter quite a bit more.

What’s the default experience for investors regarding frontier markets and how does one manage this risk?

Every sovereign default experience is unique in some way. The decision to default is ultimately a policy choice, and every policy choice is inherently political in nature, in that it reflects an attempt to balance competing interests across economic, political and popular/social interests. So there’s certainly a political dimension to defaults, and that implies that the politics that shape a sovereign’s political and economic context also shape decisions with respect to debt repayment. This is essentially the “willingness to pay.” Managing default risk requires us to understand each country’s economic situation through this lens. To illustrate this, we can look at Jamaica and Argentina. Jamaica’s debt burden peaked north of 120% of GDP 10 years ago. It was a pretty clear-cut candidate to default on external debt, and its credit ratings reflected that risk. But the political response went in the opposite direction, and the country committed itself to sustained fiscal consolidation. The debt burden is now around 78% of GDP. In a situation like that of Argentina, we’ve seen almost the exact opposite response. Bondholders provided the country’s authorities with fiscal breathing room in the heart of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Fernandez administration, in turn, used that space to spend on unsustainable, politically motivated objectives. So, it’s absolutely critical to understand a country’s political incentives when we’re thinking about default.

But there are also some common factors across defaults. It’s fairly straightforward to identify elevated external vulnerabilities in sovereign balance sheets, and to assess the extent to which a country needs access to external sources of capital to avoid liquidity issues. Many of the defaults in 2020 (Covid pandemic) and 2022 (Russian invasion of Ukraine, Fed liftoff, China retrenchment) involved a country with elevated external vulnerabilities encountering an external shock (or series of external shocks). So sovereign defaults do tend to be infrequent but “lumpy,” given elevated sensitivity to commodity prices and global financial conditions.

What assessments do you make to identify balance sheet vulnerabilities?

Assessments that our EM Team make and that we believe are critical to measure and mitigate default risk in the frontier markets space include the following:

- Fiscal. Examining gross financing needs (GFNs) help investors understand the public sector’s vulnerability to external financial conditions, local financial sentiment and the evolution of public sector revenues and expenses.

- External. We look at external financial requirements (EFRs) to assess a country’s exposure to current account shocks, financial flow reversals and broader fluctuations in the availability of US dollar liquidity.

- Financial. An analysis of the domestic financial system helps identify potential contingencies that can impact public finances.

Economic and political capacity assessment

- Economic strength. Countries with higher levels of GDP per capita, and better baseline trajectories for economic growth, are typically better-equipped to respond to economic, financial or balance-of-payments shocks. We also consider economic buffers, including FX reserves and financial system liquidity, in this assessment.

- Institutional strength. We rely on a detailed assessment of governance and social factors to assess a government’s technical and political capacity to respond to shocks.

Debt sustainability analysis (DSA)

- Standard DSA. Examines the evolution of public debt levels as a function of growth, the primary fiscal balance and real-interest rates.

- Economic structure, reform needs and potential growth. We consider a country’s DSA in the context of its economic structure, the stability of political equilibria and expected reform needs to assess potential development paths.

Environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors

- Climate risk and climate change. Can dramatically impact economic cycles, helps identify material structural risks that must be addressed over the medium and long term.

- Sustainability, natural and human capital. Underpins the viability and quality of longer-term growth.

- Social factors. Condition the governance context, determine the envelope of “acceptable” policy options.

- Governance. Public finances are a policy choice; good outcomes require good governance.

What’s your investment thesis behind having an allocation to frontier markets?

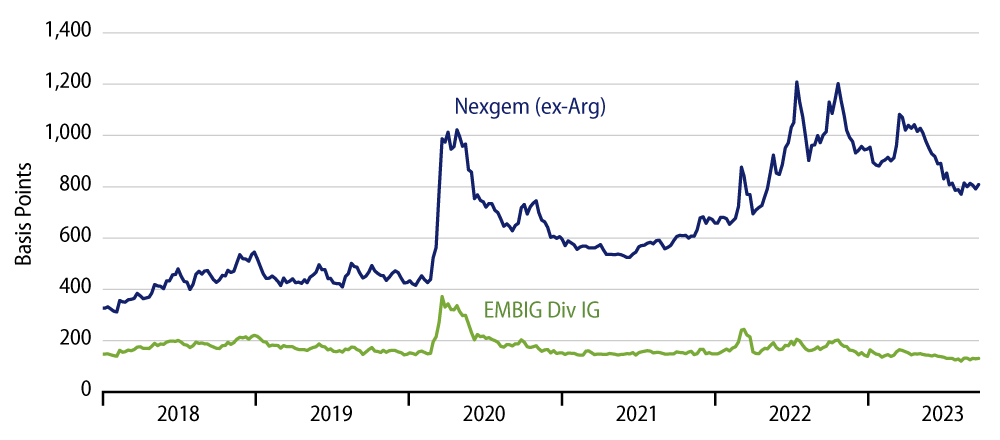

We believe global central banks are nearing the end of their hiking cycles, that US growth will remain relatively resilient and that China will provide (just) enough support to avoid being a headwind. So our base case remains broadly aligned with the macro scenario we outlined in early May. And, in that context, EM debt looks compelling on both an absolute and relative value basis. Turning to frontier markets, specifically, we see the risk/reward asymmetry relative to other sectors within the broader EM universe as quite attractive. Valuations remain historically wide, and both idiosyncratic and event-driven opportunities offer an opportunity to reduce “beta” to global macro factors and benefit from less-correlated, fundamentally driven credit inflection points.

Bear in mind that frontier markets is a total return market that harks back to the way in which EM was initially viewed in the early 1990s. With today’s more sizable universe of frontier debt, an asset manager such as Western Asset can construct a portfolio or sleeve reflecting several diversified, idiosyncratic investments. Bringing these elements together creates an investment return profile that is less of a beta play on macro factors and can result in a better total return distribution.

With that said, in a scenario of eventual loosening of global financial conditions, we’d expect frontier markets to be one of the primary beneficiaries.