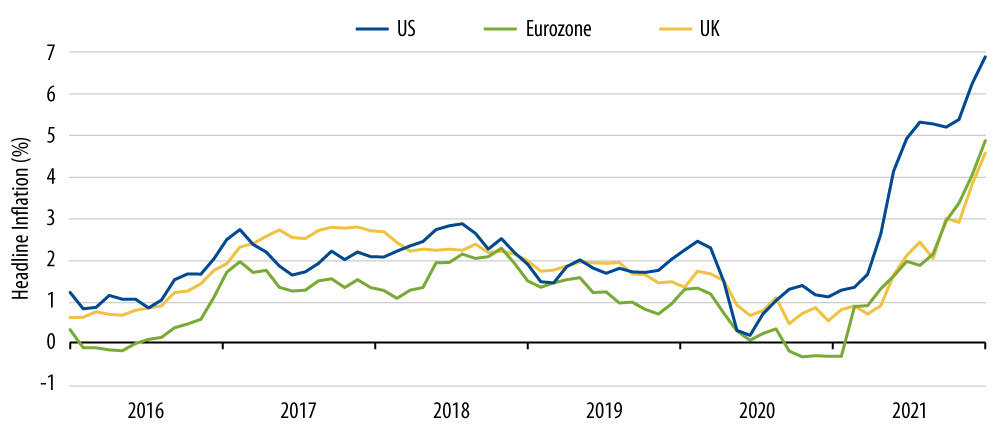

With headline inflation remaining elevated globally (Exhibit 1) we revisit the specific inflation drivers in three major economies: the US, eurozone and UK. We highlight differences in recent inflationary impulses, our expectations for inflation trajectories over the coming months and the potential implications for bond yields.

US

US inflation has run much higher in 2021 than either Western Asset or the Federal Reserve (Fed) projected just a year ago. This upside surprise has been driven primarily by three key factors: 1) Energy prices have risen approximately 50% over the last 12 months; 2) the switch in demand from services to goods during the Covid pandemic continued in 2021, and 3) bottlenecks in goods production continued to push goods prices higher.

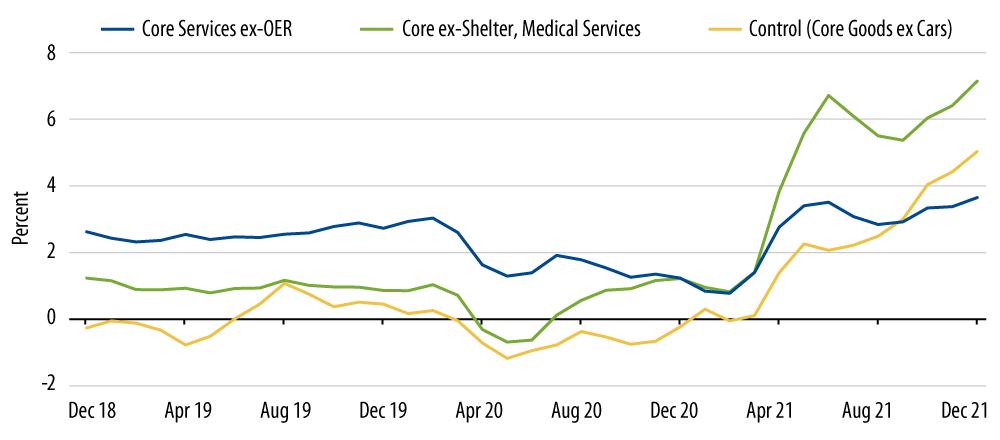

This sudden increase in goods demand put a strain on production and delivery systems already impacted by the pandemic. Prices surged across goods that had seen little inflation, and even deflation, for the past two decades (Exhibit 2). Service inflation, which had run above headline inflation for the past two cycles, declined at first but has since recovered and is now close to average levels. A major component of service price inflation, which has only recently exceeded prior trends, is the cost of shelter.

The strength in rents and home prices we have seen since late-2020 will push shelter inflation to around 5% for at least the first half of 2022, keeping core inflation elevated over this period. However, more recently we are starting to see signs of slowing in terms of increases in rents, prices and house-buying activity.

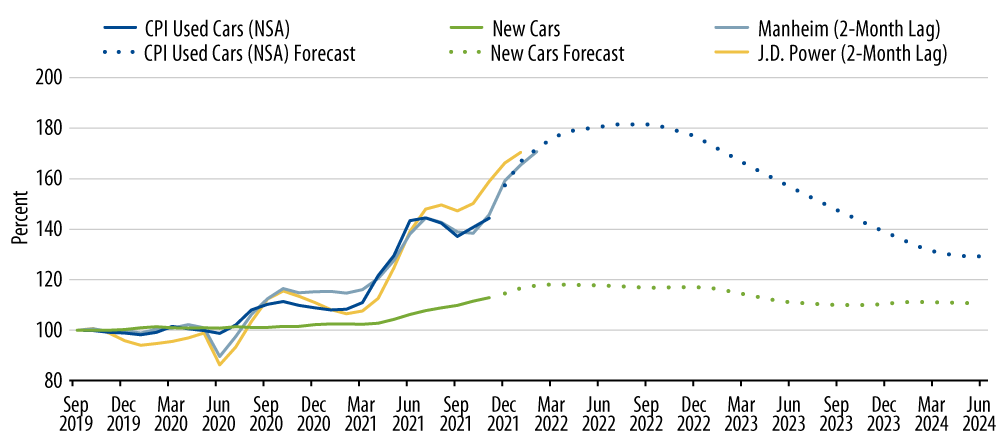

The poster child for bottleneck pricing is used cars, which are up 50% over the last year driven by higher demand for autos due to the pandemic migration from cities to suburbs combined with globally constrained production that has yet to fully recover. While used car auction prices are still at their highs, monthly gains have subsided recently and we anticipate them peaking in 1Q22 as new car production comes back on line (Exhibit 3).

Despite the initial pandemic impacts on both demand and supply lessening, inflation should continue to remain high through the first two or three months of 2022. While housing inflation will likely persist, energy prices have already begun to turn lower and some goods prices, such as used cars, should also fall. This will likely lead to inflation dropping sharply into the latter half of the year. This, combined with the Fed ending TIPS-supportive asset purchases at the end of 1Q22, and the potential for higher policy rates thereafter should push real yields higher, especially in the 5-year tenor.

EUROZONE

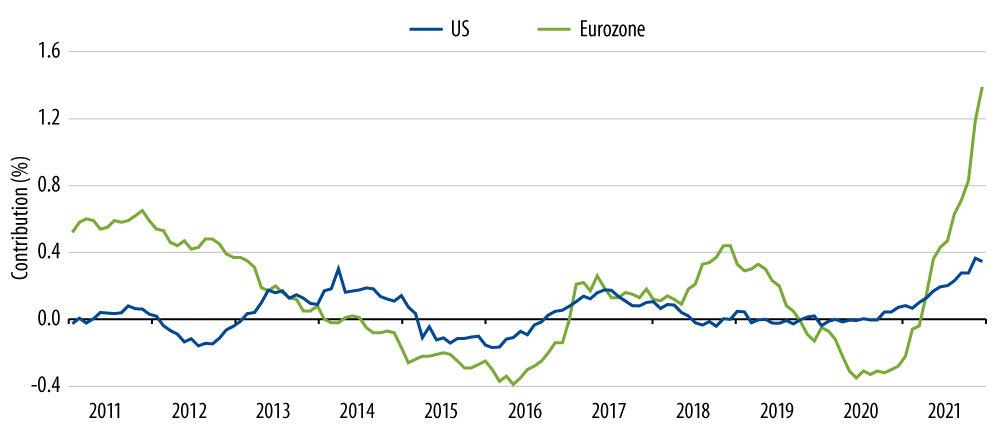

Inflation in the eurozone has likely peaked, but over the next three months the risks are that it does not fall back as much as expected on the headline measure. This stems from energy services which is a combination of electricity and heating costs. Exhibit 4 illustrates that this is a much bigger part of the inflation story in the eurozone than in the US.

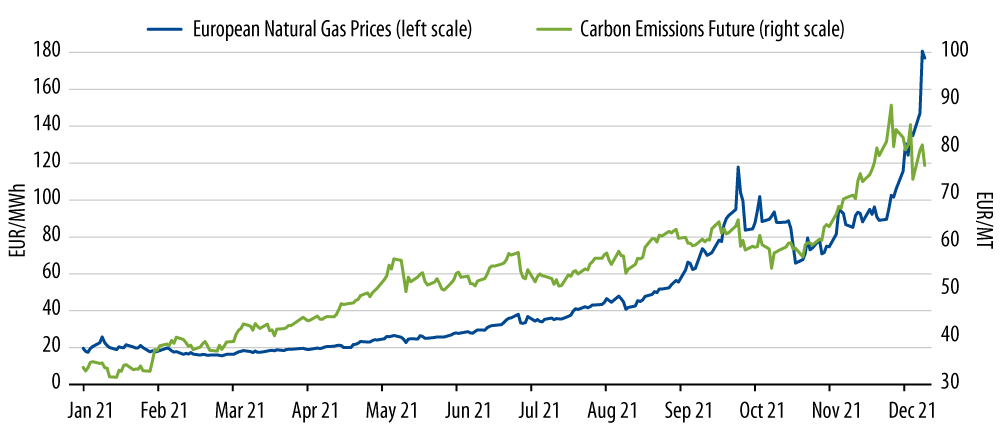

The rise in energy service inflation is a combination of rising natural gas and carbon prices in Europe. Natural gas prices have been rising as storage levels are low after a cold winter last year; flows from key supplier Russia have been lower than average as have electricity generation from both wind and solar. On the carbon side (which at current prices is around 60% of the wholesale electricity price), some electricity producers have switched from natural gas to less expensive coal, which has increased the demand and prices for CO2 emissions quotas. The scale of these increases is highlighted in Exhibit 5.

In the last forecast round, the European Central Bank (ECB) raised its annual inflation forecasts for 2022 to 3.2% and to 1.8% for 2023 and 2024, respectively. This is broadly in line with current market pricing, in contrast to the US and UK, both of which have market expectations for inflation higher than their respective central banks’ forecasts. With ECB asset purchases falling, net supply rising and the potential for sticky headline inflation in 1Q22, this should keep pressuring nominal yields higher.

UK

Inflation in the UK rose more than expected in 2021, driven by the dynamics described earlier for the US and eurozone: supply-chain disruption, bottlenecks amid supply and demand shocks during the course of the pandemic, and significantly higher energy prices. While the effects of the pandemic clearly dominated, another factor to consider is the impact from the UK’s withdrawal from the European Union, particularly since the end of the Transition Period, which concluded at the end of 2020.

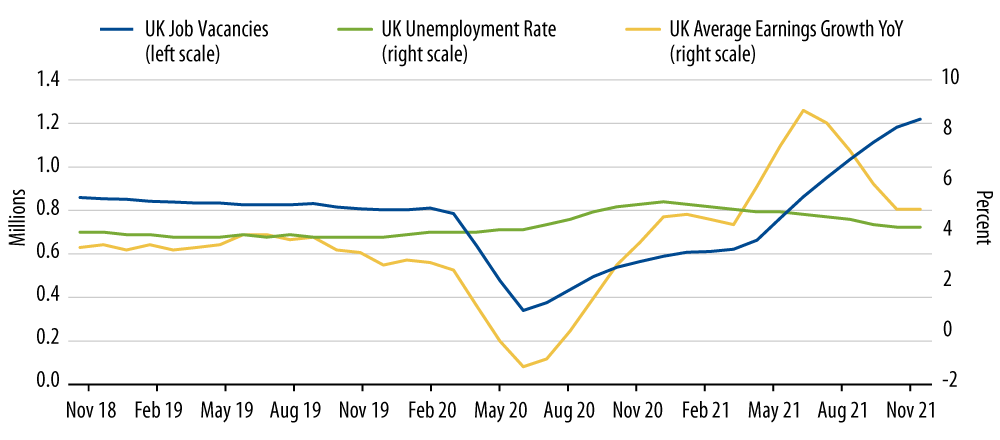

As the fog of the pandemic clears, there are two main ways that we expect the “post-Brexit” effects on inflation to become clearer. The first relates to the labour market, which a large number of European nationals left the UK during the Covid pandemic. Consider for example a European national that had moved to the UK in recent years, worked in hospitality and lived in rented accommodation—if pandemic rules meant that their job was lost or furloughed and there were heavy restrictions on any social interactions, returning to live with family in their home country would likely be an appealing option. Post-Brexit visa rules make it much more difficult for EU nationals to work in the UK and employers have reported significant difficulties in hiring. Against this backdrop, the Bank of England (BoE) is concerned that the tight labour market (the unemployment rate is 4.2%in the UK, and there are a record 1.2 million job vacancies, per Exhibit 6) will continue to exert upward pressure on wage growth, which could combine with the current high inflation to cause medium- and longer-term inflation expectations to become entrenched. Against these concerns, in December 2021 the BoE became the first G-7 central bank to raise interest rates since the outbreak of the pandemic.

The second way we expect inflation to be affected is due to greater trade frictions post-Brexit. While there are hopes that businesses will adjust to the new rules and requirements, there are costs associated with doing so and these could feed through into higher consumer prices.

The BoE expects inflation to peak around 6% in April 2022 before falling back in the second half of the year. Given the backdrop described, we expect the BoE’s concern over higher inflation becoming entrenched to persist, which should lead to further policy-rate normalization and an underperformance of nominal and inflation-linked gilt yields.