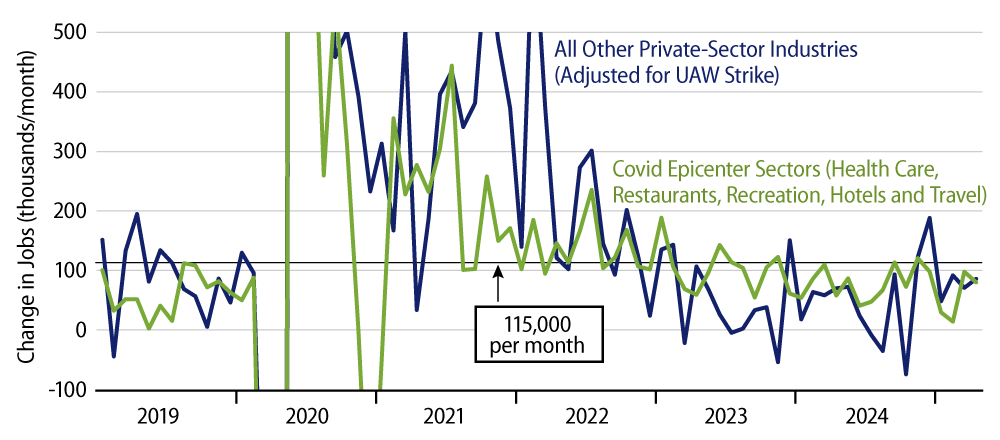

Private-sector payroll employment rose by 167,000 jobs in April, although that was partially offset by a -47,000 revision to the March employment tally. Job gains have been pretty steady lately and evenly distributed between sectors hard hit and less hard hit by the Covid shutdown of 2020. As you can see in Exhibit 1, both of these segments of the economy have been showing generally slower recent job growth than the 115,000 per month gains seen prior to the pandemic. Then again, the less hard-hit sectors have shown better job growth in each of the last six months, after job growth there slowed nearly to a halt in mid-2024.

Meanwhile, workweeks held steady, so that total hours worked rose modestly. Average wages increased a scant 0.2% in April or at an annualized rate of 2.0%. This is well below the 3.5% annual wage growth that is thought to be consistent with the Federal Reserve’s (Fed) 2.0% inflation target. This continues a trend of the last six months, over which hourly wage growth averaged a 3.3% annualized rate. Other data released today show a similar slowing in the Employment Cost Index, which adjusts the hourly wage data for inter-industry job shifts inter alia.

The jobs data indicate a generally steady labor market, and both the modest pace of job growth and the slowing pace of wage change are right in line with the Fed’s designs for inflation.

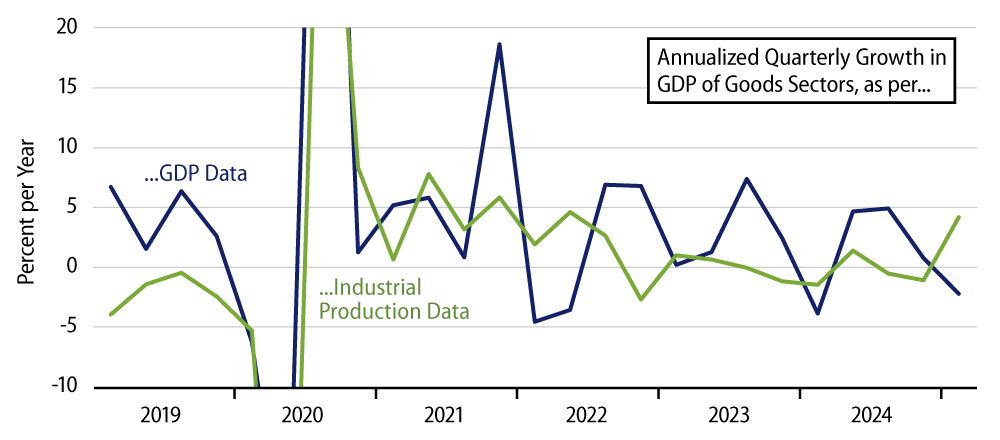

In data released Wednesday, the Commerce Department reported a -0.3% rate of decline in real GDP in 1Q25. We believe this is a case of bad data, as it is quite inconsistent with what production indicators for the economy suggest for 1Q. GDP is reported as declining solely because of a drop in goods-sector output. Yet, as Exhibit 2 shows, Fed data on industrial production (IP) for these same goods sectors show not just positive, but accelerated 1Q growth.

Yes, it was a big increase in imports that drove the 1Q goods GDP decline, but those imported goods went somewhere—either into inventories or into spending. Within the GDP data, consumer spending on goods, business spending on equipment and increases in goods inventories all rose in 1Q, but their combined rise was much less than the increase in imports; hence the decline in goods GDP. If this were really true, goods output indicators should have shown an accompanying 1Q decline. Instead, they showed accelerated growth.

As is clear from Exhibit 2, these indicators often (usually?) provide very different portrayals of goods sector activity. The differences are especially notable for 1Q25, in that the goods GDP data give rise to a decline in overall GDP even while other goods-sector data indicate an improvement in growth.