The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released its Sixth Assessment Report last month. Unsurprisingly, the report warns that global temperatures are almost certain to rise by more than 1.5 degrees Celsius by the year 2040—a direct result of the human impact on climate change. While the report calls on policymakers, corporations and citizens around the world to take action, its conclusions also increase the pressure on countries to strengthen their national emissions commitments ahead of this November’s UN Climate Change Conference (COP26).

As investors in sovereign debt, the effects of climate change are already apparent. Longer and more frequent heatwaves, drought, flooding and other examples of extreme weather have materially impacted a number of countries in recent years.1 The range of potential climate-change scenarios and the variable impact those changes will have across countries2 point toward the need for a country-specific approach to assessing physical climate risks. Yet, from a collective standpoint, it’s also clear that any deviation from the targets set forth in the Paris Agreement will have a pronounced negative impact on countries around the world.3

Our sovereign ESG framework provides an important lens through which to view these challenges. The framework considers two distinct sets of factors, both climate risk and sustainability. In so doing, we’re able to consider country-specific and collective risks concurrently. This allows us to scale our research efforts more effectively, better identify engagement touchpoints and also align with key regulatory requirements that are set to reshape fixed-income markets in the years ahead.4

Assessing physical climate risk has always been a cornerstone of our sovereign ESG process. However, our approach to quantifying these risks has evolved in recent years, and now focuses more closely on the intertemporal dimensions of climate vulnerability. By considering climate risks from a cyclical, structural and secular perspective we are able to map climate factors to growth paths in a way that deepens our understanding of economic risks.

Equally importantly, this bucketing of risks helps highlight country-specific climate adaptation needs, as well as a country’s stake in mitigating longer-term global temperature rise. We view this as important for three reasons:

- First, it helps identify capital investment needs. This is an important consideration when we assess a country’s “green bond” framework, and the potential use of proceeds from any issuances that flow from that framework.

- Second, it shapes our broad environmental engagement strategy. This can include encouraging governments to prioritize and articulate climate adaptation needs, define environmental objectives in the budgeting process, and adopt additional policies—such as green taxonomies—to catalyse green investment in the domestic economy.

- Third, having a clear understanding of the long-term risks stemming from climate change facilitates focused dialogue around Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and emissions reduction—an area where progress still meaningfully lags targets.5

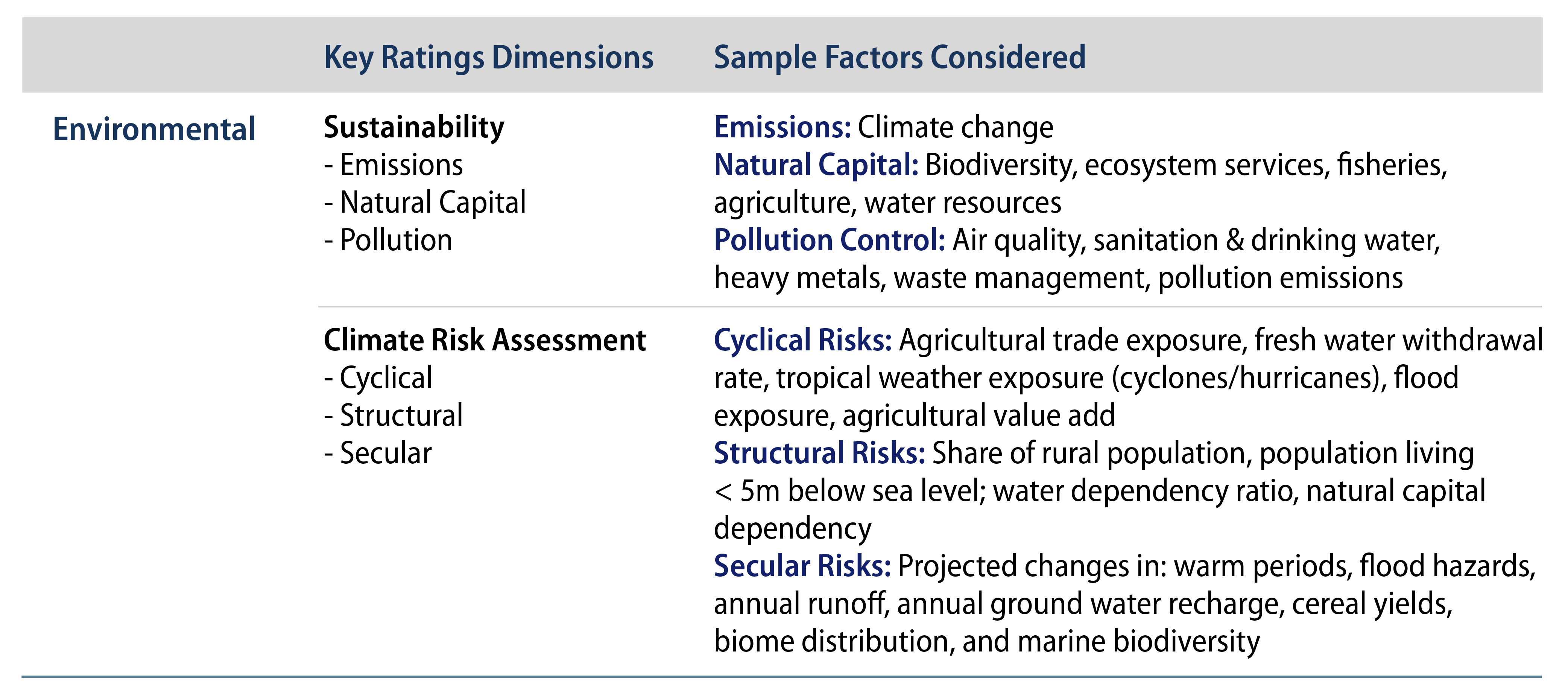

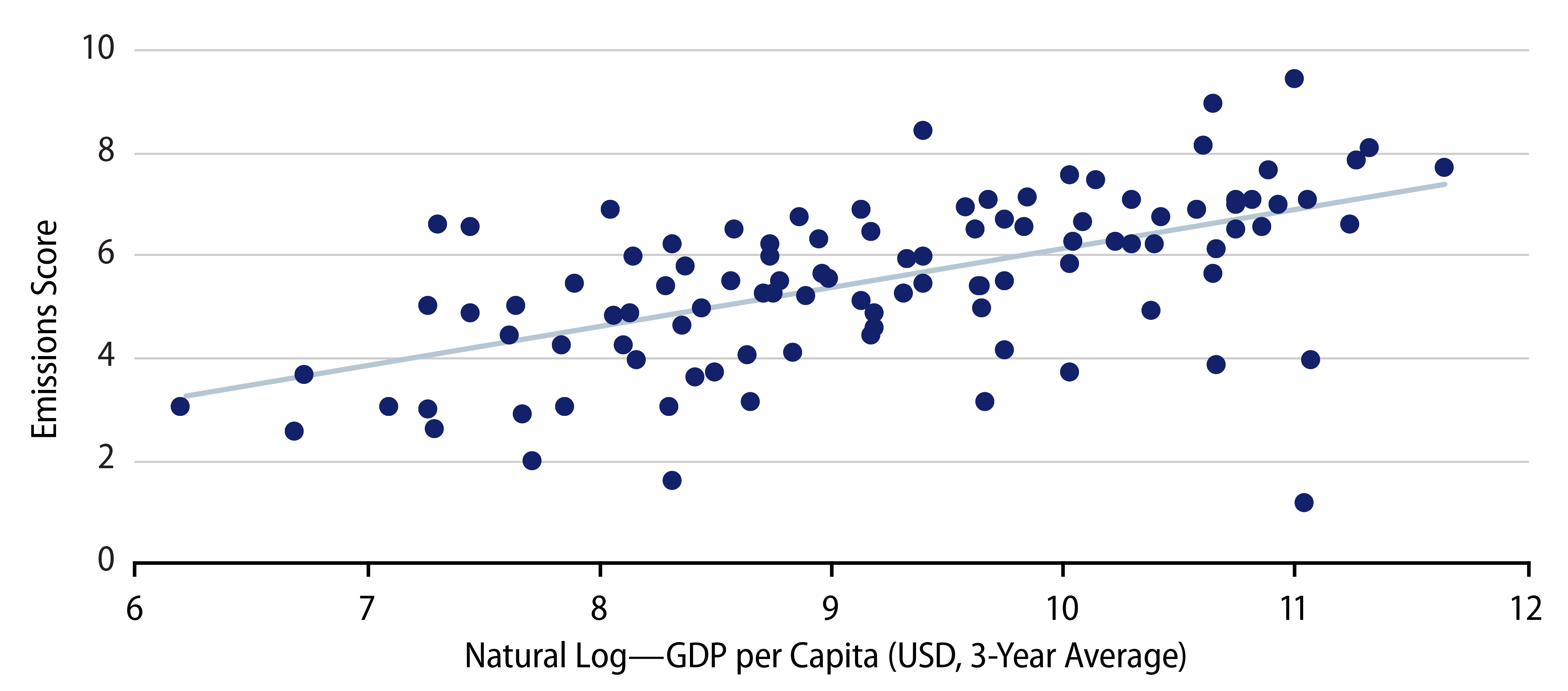

An effective engagement strategy also requires us to understand how countries currently compare to one another from a sustainability perspective. Our environmental framework (Exhibit 1) provides us with a broad view of sovereign performance across 27 climate-related indicators, including emissions trends, effective management of natural capital and pollution control. Using data from the Yale Environmental Performance Index (EPI), we’re able to assess countries’ performance on emissions objectives, and benchmark each sovereign’s performance against those at a similar level of economic development, providing a clearer picture of which countries are over-/under-performing on global decarbonization objectives (Exhibit 2).

Western Asset has long considered ESG factors, including climate risk and opportunities, in its investment process. As the connection between financial returns and sustainability factors has grown more apparent, climate and other ESG risks have become a central concern for other investors as well.6 In our proprietary sovereign ESG framework, we focus on the unique contributions that ESG brings to sovereign economic growth and sustainability. By applying this framework in conjunction with macroeconomic and financial analysis, our investment team seeks to identify the best opportunities across the diverse sovereign bond universe.

ENDNOTES

1As an example, Argentina’s 2018 drought played a major role in the country’s eventual balance-of-payments crisis, the reverberations of which are still being felt today.

2See for example: https://interactive-atlas.ipcc.ch/

3ME Khan, et al. “Long-Term Macroeconomic Effects of Climate Change: A Cross-Country Analysis.” IMF. October 2019. Accessed, 24 Sep 2021. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2019/10/11/Long-Term-Macroeconomic-Effects-of-Climate-Change-A-Cross-Country-Analysis-48691

4While there isn’t a single approach to “green” regulations globally, our framework is generally consistent with the environmental categories and bucketing laid out by the EU Taxonomy regulation.

5See for example: https://unfccc.int/news/full-ndc-synthesis-report-some-progress-but-still-a-big-concern

6See, e.g., A Practical Guide to ESG Integration in Sovereign Debt (UNPRI), Selected Academic Research, p. 56.