The Japanese yen hit a 20-year low of around ¥130 versus the US dollar late in April for the first time since April 2002. More importantly, its real effective rate is at its lowest level since the early 1970s (Exhibit 1).

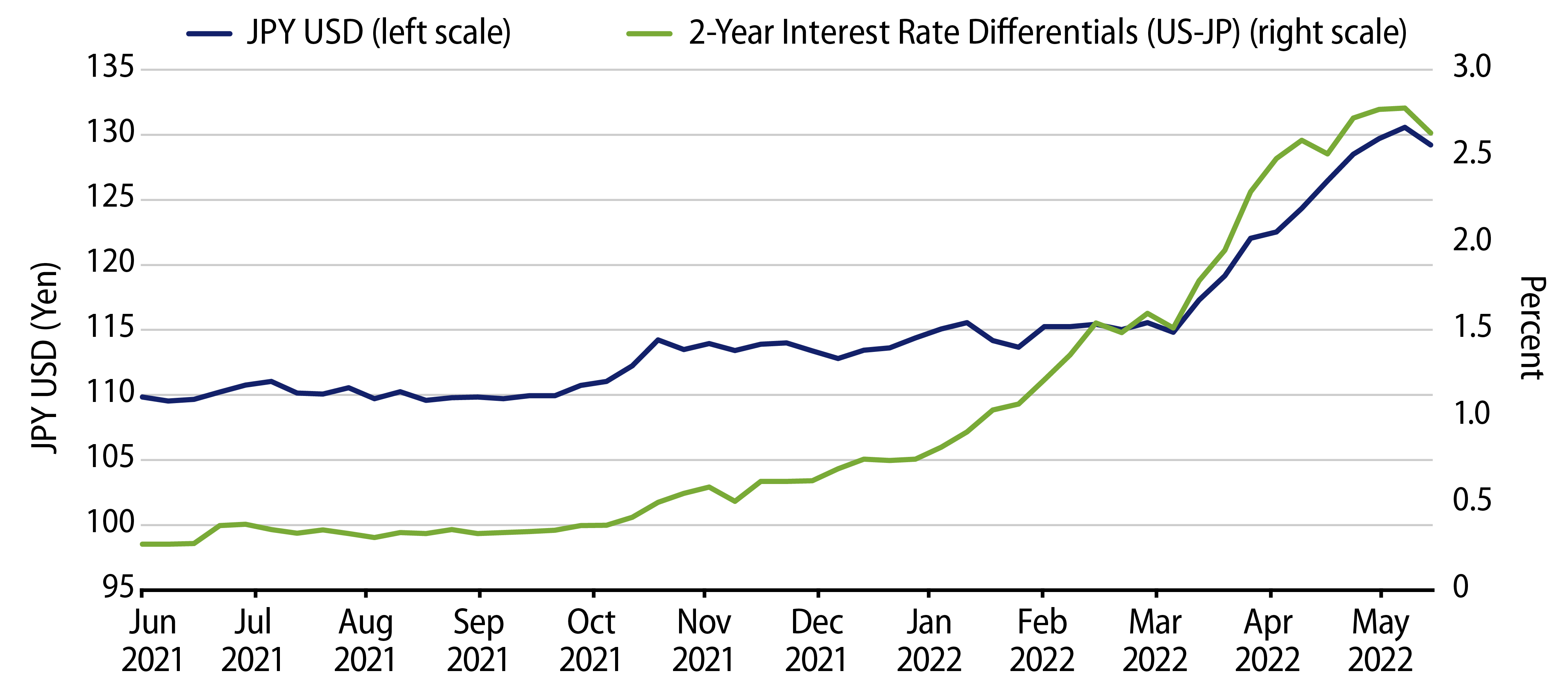

The yen weakness accelerated after the Bank of Japan (BoJ), in its April monetary policy committee meeting, reinforced its commitment to the Yield Curve Control (YCC) framework to maintain low interest rates. Meanwhile, central banks in the US and Europe instead are moving toward monetary tightening due to rapidly rising inflation. In addition, the reinforced YCC (whereby the BoJ will offer to purchase 10-year JGBs at 0.25% every business day with no quantitative limits) may well lead to quantitative easing (QE) when interest rates rise outside Japan, whereas other central banks are preparing for quantitative tightening (QT). In other words, the stance of the BoJ is in sharp contrast with that of many other central banks (Exhibit 2). Why and to what extent is the BoJ currently so different?

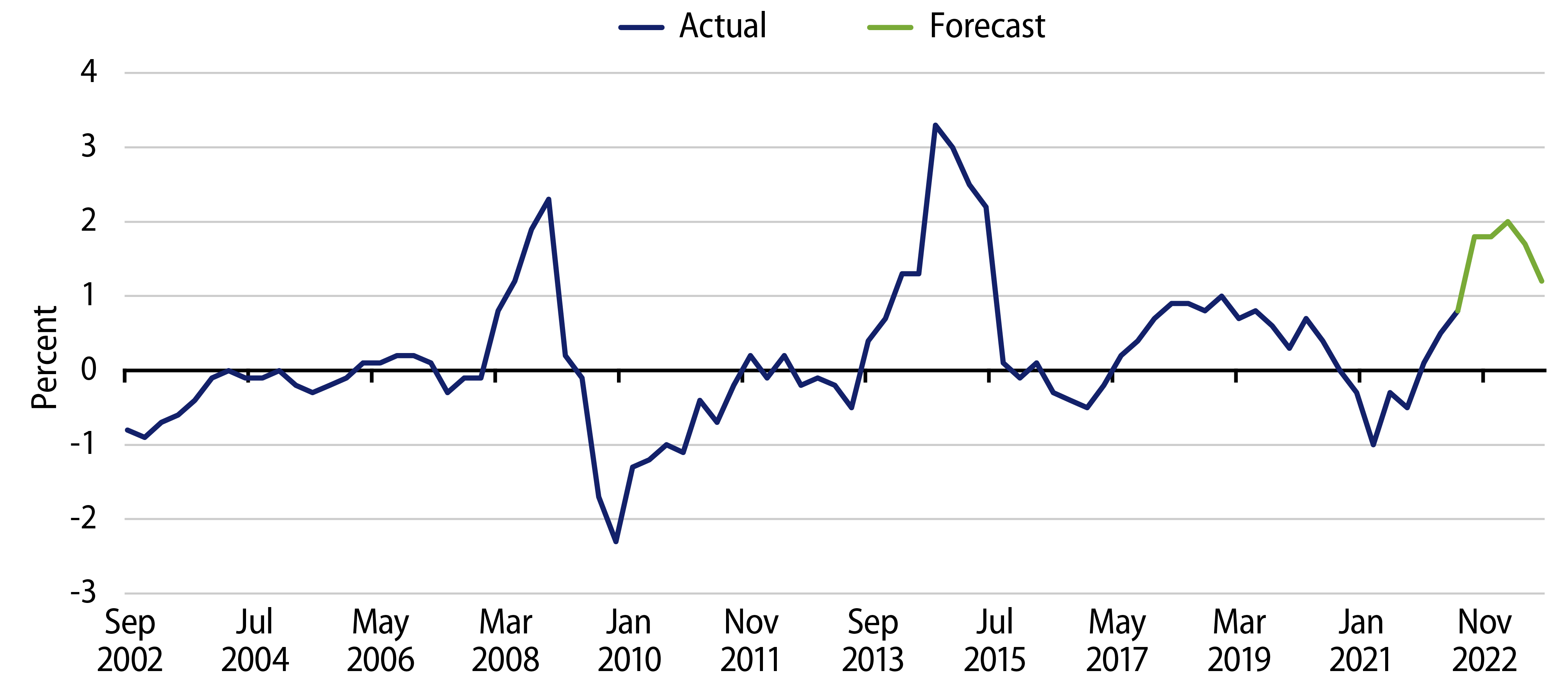

First, from a cyclical perspective, inflationary pressure in Japan remains relatively weak because the economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic has also been relatively slow (Exhibit 3). In fact, Japan’s GDP has not yet reached its pre-pandemic level, unlike most other developed market (DM) economies. Prices are rising broadly in Japan, though, and some forecasters expect that in 2022 inflation will rise above the BoJ’s target annual inflation rate of 2%. Indeed, the BoJ’s latest projected rate of core inflation (excluding fresh food) could reach 1.9% for the year ending March 2023, up from its previous projection of 1.1%. However, the BoJ believes that current price increases are unlikely to be sustained because they are caused primarily by higher costs of energy and raw materials rather than by robust consumer demand. This leaves the BoJ with no option but to keep interest rates low.

Second, from a structural perspective, long-standing difficulties such as the ageing population, inflexible labor markets and increasing public debts have persisted alongside chronic weak inflation. Contrary to some resulting pessimism, the labor supply has increased more than expected because a broader swath of laborers, including foreigners, women and the elderly, have started participating in the labor markets. Obviously, this has been a positive development in light of potential growth, but it has weighed on wages because the increase of the labor supply is compensated with lower wages. Otherwise, structural reform, in particular in the social security system and labor markets, has been very slow. The slow progress in structural reform has prevented resources from being allocated effectively, industrial structures from changing and labor productivity from improving. As a result, corporations have little incentive to increase wages because of low productivity, growth and labor mobility. In addition, chronic weak inflation has persisted over multiple decades. Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s new form of capitalism, the details of which will be unveiled in June, seems to focus on more even distribution of income and investments in people and growth but at the same time emphasizes the downside(s) of a neoliberal approach. In other words, Kishida looks to retain the first and second arrows (bold monetary easing and flexible fiscal spending) of Abenomics but has not yet shown clear directions in terms of the third arrow (structural reform).

Finally, in reality, monetary policies can no longer be implemented independently from fiscal policies given the size of the public debts in Japan, despite its lawful independence from the government. The YCC framework the BoJ has successfully developed will be critical in order to keep the nominal interest rates lower than the nominal GDP growth rate to ensure fiscal sustainability with reasonably small costs. The government and the BoJ jointly made the accord in 2013 to strengthen its policy coordination in order to overcome deflation and achieve sustainable economic growth with price stability. We need to remember that this accord remains effective.

So, what might prompt the BoJ to change? At a minimum, inflation higher than 2% needs to be observed over several months before the BoJ will make a change. How likely is that? The current market expectation is that inflation will exceed 2% this year but decline below 2% next year. Still, higher inflation rates overseas were first considered transitory whereas actual developments in inflation turned out to be much stronger and enduring. How could Japan be an exception? Indeed, in April, headline CPI in the Tokyo region increased 2.5% year-over-year (YoY), up from 1.3% YoY in March. In addition, YCC is pro-cyclical in that higher inflation expectations lead to lower real interest rates given the capped nominal rates. The lower real interest rates with the possibly extended BoJ balance sheet may boost growth, cheapen the yen and increase the inflation expectations. This pro-cyclical process would work well when overseas inflation is strong.

We should not rule out the possibility that inflation over 2% will persist for a while. This could be the last opportunity that the BoJ would have to achieve its 2% inflation target before the end of Kuroda’s tenure in April 2023. The BoJ might make some changes in policy if the inflation target is somehow met. However, any changes the BoJ makes would likely be marginal, because the Japanese economy still needs reasonably low interest rates for the many aforementioned reasons.

Last, the recent depreciation in the yen seems to have already priced in the expected interest rate differentials between Japan and the US because the aggressive rate hikes are fully priced in the US markets (Exhibit 2). However, the structural weakness may well weigh on the yen if the current account falls into a persistent deficit from higher energy and food prices due to the war by Russia. At this moment, we expect that the yen is unlikely to rebound sharply in a consistent manner in the near future.