Private-sector payroll jobs were reported as rising by 443,000 jobs in January. Large gains occurred in essentially every industry, accompanied by increases in the workweek. Meanwhile, average hourly wages were reported rising at a 3.7% annualized rate for all workers and at a 3.0% rate for production and nonsupervisory workers (who actually get paid by the hour).

We’ll skim through the details shortly. First, the big issue is how this will affect Fed policy deliberations. If the Fed’s sole criterion for success in its inflation fight is declining jobs and higher unemployment, then today’s report means many more rate hikes to come. However, if the Fed acknowledges that actual payrolls levels are still hugely below pre-Covid trends and so seek only to preempt a wage-price spiral, this could actually be a comforting report.

The latter slant is no doubt wishful thinking, but it could be some part of the reasoning of Mr. Powell and Company. They likely had some advance word on the payroll count when they deliberated earlier this week, and yet the tone of both the FOMC statement and Powell’s press conference remarks softened at least a bit from what we had heard previously.

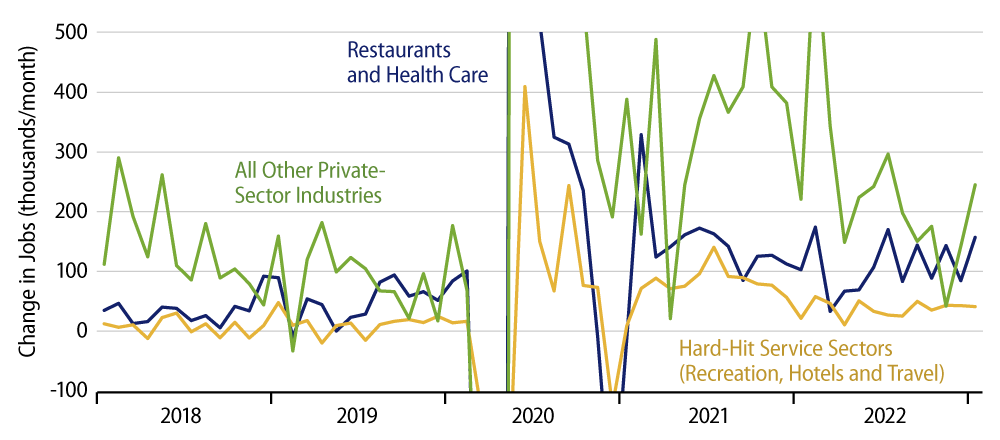

Besides the usual monthly sources of choppiness, today’s data also included benchmark revisions and January seasonality effects. The benchmark revisions added about a million jobs to net gains over the 22 months since March 2021. Revised seasonal adjustments also changed the monthly pattern of job growth, so that some months of 2022 actually now show slower job growth than before, though most months show stronger growth. And even with those upward revisions, private-sector payroll jobs are still more than 3 million below their pre-Covid trends.

Speaking of seasonality, in January, every industry but accounting is shedding workers in the wake of the Christmas holiday and in the face of winter cold. Thus, before seasonal adjustment, private-sector jobs declined by 2,166,000, and government touches morphed this into the aforementioned 446,000 gain. Seasonal effects vary from year to year, so the “signal-to-noise” ratio for the January data is likely low.

Of course, seasonal adjustment “takes” job growth from other months and sprinkles it into January and other seasonally declining months. And it is clear that the general trend of employment has been firmly up since the late-2020 reopening. Our point is merely that if you think the January report indicates a sudden explosion of growth in the economy in January, you are reading too much into the numbers. As you can see in the chart, the January gains occurring outside industries heavily affected by the Covid shutdown look like an outlier against the general trends of the last two years. Still, again, there is clearly no weakness in jobs nor in workweeks that would give the Fed pause.

And having cited possibly technical oddities in the job gains, we should acknowledge that the same possible shortcomings could exist within the hourly wage data. As always, on to next month’s report. Today’s news wasn’t a total washout for those of us hoping for some relief from the Fed, but it came close.