Private-sector payroll jobs grew by +136,000 in June, but that was largely offset by a -86,000 revision to the June payroll level estimate. Average workweeks declined very slightly, so that total hours worked rose slightly less than jobs, and average hourly earnings rose 0.29%.

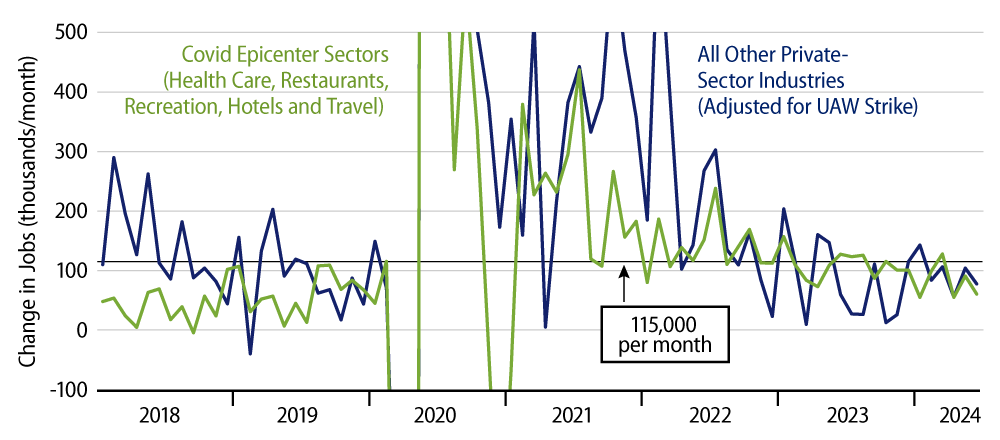

In analyzing the payroll data, we have been splitting the economy up between sectors heavily affected by the Covid shutdown and everybody else. The Covid-affected sectors—we call them the Covid epicenter—were very late in the game in terms of restaffing following the shutdown, and so they have provided a tailwind to job growth in recent years, as they continued to add jobs at a relatively rapid rate in order to get back to pre-Covid staffing levels.

For the rest of the economy, ''normal'' staffing levels looked to have been achieved by the end of 2022, so much so that these sectors saw a noticeable slowing in job growth in late-2023 (see Exhibit 1). That slowdown looked to be reversing early this year, as job growth in these sectors rebounded.

In recent months, we have seen some slowing in job growth in both the Covid epicenter sectors and in the rest of the economy. One sector where this slowdown did not occur was health care, which continued to add jobs in June at a strong clip. Of course, this underscores how much job growth has been slowing elsewhere.

That is, over April, May, and June, total private-sector jobs have risen by only 108,000, 193,000, and 136,000, respectively, even though health care jobs have risen by 59,000, 60,000, and 49,000, respectively. Health care is only 13% of private payrolls, but it has provided 38% of private payroll growth in recent months.

Even with those the health care boosts, you can see in the chart that private-sector job growth has fallen below pre-Covid growth rates lately. No, the labor markets are not in decline. Job growth is still okay lately, but it is not robust.

As for wages, if the June hourly wage gains were sustained, they would result in annual growth of 3.5%, right in line with the unofficial targets for wages that the Fed has suggested. For both the last six and 12 months, wage growth has averaged 3.9% per year. So, wage growth is close to the Fed’s targets, and the June data are at least a hint that there is further deceleration there.

In our last post, we speculated that the modest—in-target—PCE inflation seen in May along with other economic data put a September Fed rate cut in play. We think today’s employment report increases those chances. The Fed has said that it wanted labor markets to cool, but it never said it wanted them actually weak. With job growth having fallen to rates slower than what we saw pre-Covid, with much of that growth centered in health care, and with wages and total hours worked also slowing, we likely are at a point where further softening would connote actual weakness … in which case it might be time for the Fed to start cutting.