Private-sector jobs increased by 426,000 in March, on top of a +129,000 revision to the February estimate, as per data released today by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), within the Labor Department. Job gains have been fairly steady, robust and widespread throughout the last year. Recent gains pale alongside the massive increases that occurred in late-2020, but that is only to be expected as various sectors begin to approach full recovery from the ravages of the Covid shutdown/recession/repression.

The 590,000 per month pace of job gains seen over the last six months would have signaled explosive growth in the pre-Covid economy. In the current environment, however, such gains are necessary to continue to bring the economy back from Covid. Even at the recent pace, it will take until mid-2023 to return payroll jobs back to their pre-Covid trend path. Such a four-year recovery path would be relatively long by historical standards.

Of the aforementioned revision to February estimates, essentially all of that (126,000) occurred in retailing. Retail jobs have risen by 2% over the last six months, even while real retail sales have declined. Assuming that both indicators are accurate, it would appear to be the case that retailers have added workers not to accommodate further growth, but rather to return staffing to more normal levels after the bare-bones operating conditions of the last 21 months. That same process is in place in other industries as well.

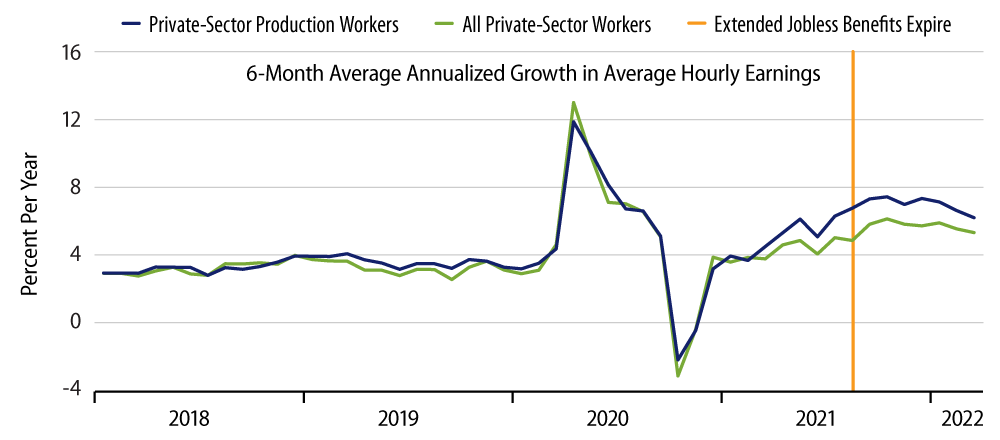

Meanwhile, labor force participation continues its recovery. Extended unemployment benefits largely expired in August of last year. Since last October, labor force participation among prime-age (25-54) workers has increased by 1.9 million, with the labor force participation rate for that cohort rising from 80.7% to 81.5%. Expiration of extended benefits in late-2014 drove a similar rebound in the labor force and employment in 2015.

We focus on prime-age workers here because some analysts have suggested that the drop in participation seen during Covid largely reflected retirement by Baby Boomers that was not likely to be reversed. The fact is, however, that participation rates dropped across the board, and, again, there has been a steady rebound within prime-age cohorts. And, actually, the rebound in participation rates among both younger (under 25) and older (over 54) workers since October has been just as impressive as that for prime-age workers.

Presently, the increased incentives to work are helping the economy to recover from shutdown-induced losses. They are also working to alleviate the tightness of the labor market that Federal Reserve Chair Powell and others assert to be in place. As seen in the accompanying chart, the pace of growth in average hourly wages has been steadily decelerating since shortly after that expiration of benefits.

Job growth conditions are more favorable than we were indicating here just three months ago. Then again, it can be said that the better growth has been driven by increasing labor supply as much as labor demand. There are indications extant that the much-vaunted labor market tightness is easing, even with the robust job gains.