In the past three months, we have seen extraordinary policy initiatives from both the Federal Reserve (Fed) and the federal government (feds), so much so that in a post here a few weeks ago, we argued that policy had already done as much as it could do and should cease further stimulative activity. In many folks’ minds, the Fed has already done too much, and they believe a bout of substantially higher inflation is coming to the US.

We understand these fears, but we believe they are overstated. We concede that the Fed’s 2020 policy response has served as a much more effective “antidepressant” compared to what it produced in response to the 2007-09 global financial crisis (GFC). Still, as yet, the Fed’s actions have been just that: antidepressant. They have worked to forestall more distressed financial market conditions and the more depressed economy that would otherwise have occurred had the Fed done nothing.

However, the Fed has not worked to provide net stimulus. That is, we judge the depressive effects of the shutdown and related panic to be as large as the effects of the Fed’s actions to date. Therefore, we believe that as long as the depressive effects of the crisis are in place, we will not see inflationary behavior in the economy.

When those depressive effects start to ease, the Fed will have to move to withdraw its “stimulus” from the economy, but that will be a fairly easy project. It need only tamp down the expansive effects that will occur as businesses and households resume more normal operations and begin to work down the precautionary balances they have accumulated during the crisis.

In terms of this buildup in precautionary balances, the current crisis is merely in line with its non-pandemic predecessors. At the outset of the Great Depression and related stock market crash then, businesses and households rushed to accumulate cash. They did the same thing at the outset of the GFC. The urges were similar this time around, even if the driving facts and related economic circumstances were different.

In all these cases, people demand cash and cash balances to hold, NOT to spend. In terms of the quantity equation, the velocity of money fell as fast as or faster than the money stock rose, so that total spending failed to increase, and pressure on the aggregate price level was negative (downward), not positive (upward).

In fact, in the 1930s, the Fed did essentially nothing. In the face of a run on the banking system, it failed to provide any injection of liquidity (its balance sheet failed to expand). The banking system collapsed, the money stock imploded—alongside the plunge in velocity—and so did the economy.

During the GFC, the Fed waited until the crisis was already underway before providing any liquidity, but then it made up for lost time. Its balance sheet expansion then (QE) failed to drive any expansion in the money stock (or in the economy), but it did prevent a bigger implosion than what we actually saw.

My take is that the imposition and enforcement of bank capital requirements during the GFC prevented the QE then from driving any monetary expansion (or inflationary pressure). While banks had more than ample reserves, thanks to QE, they did not have sufficient capital to increase lending or deposits. As a result, there was no pressure then for monetary expansion nor economic expansion.

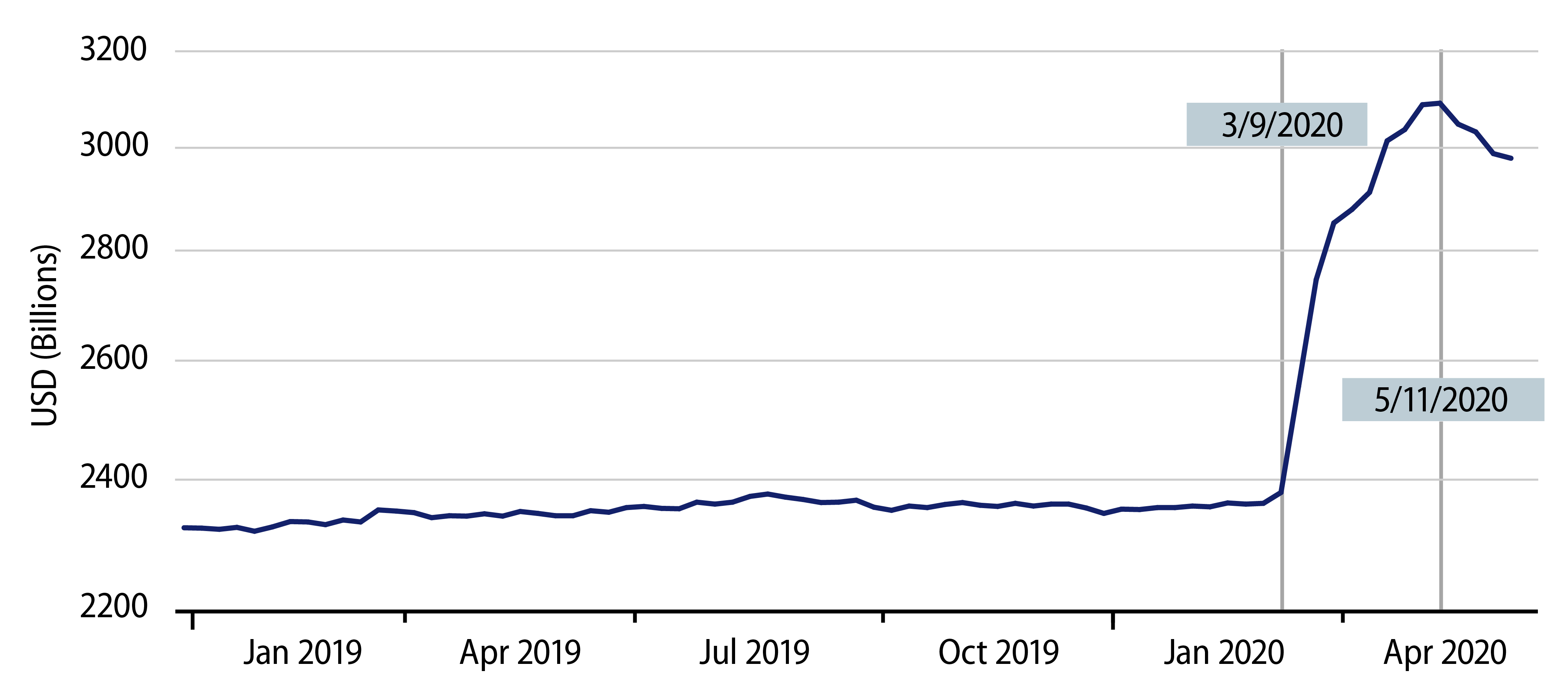

The present Fed policy mix is different in that regard. Capital requirements have been suspended and/or ignored, at least for a while. In turn, the Fed’s $2.9T of liquidity injections since February 26 have driven $0.6T of increases in bank lending and $2.7T of increases in the money stock (M2). Again, the increases in bank lending and money stock are developments we did NOT see in response to QE during the GFC.

However, again, what the present crisis shares with its predecessors is the demand by businesses and households to hold precautionary cash. All of the $0.6T increase in bank lending has gone to businesses, which have also issued a tremendous amount of corporate bonds, as well as borrowing $0.1T directly from the Fed via the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP). Meanwhile, institutional money fund balances have risen by $1.0T since February 24, and these almost surely reflect increased holdings of “cash” by businesses. Of the $2.7T increase in the M2 money stock, much of this is concentrated in deposits types heavily used by businesses, such as saving/sweep accounts (up $1.4T since February 24).

Are businesses going to spend these funds any time soon? The Fed would love it if they did, but they almost certainly won’t. Business expenditures would be on new equipment and new help, and no sign of excessive (any?) growth has been seen there yet.

Meanwhile, the figures mentioned here are actually down from what we saw four weeks ago. Since early May, bank loans to business have declined by $0.11T alongside a similar decline in institutional money funds over that period. Again, my thesis is that businesses built up precautionary funds with which to ride out the COVID crisis. As economic reopening has begun in recent weeks, business angst has declined, and businesses have started to work down their precautionary balances accordingly. Notice they are working down those balances by paying down debt, not by spending the funds (whether the Fed or you want them to spend or not).

What about households? Households have certainly benefited from the CARES Act. As mentioned in our June 5 post, personal saving rates exploded to 33% in April and we have since learned that they held at an also hyper-elevated 23% rate in May. However, according to Fed data, bank lending to consumers has not increased at all since late-February. FRB financial account data show some increase in deposits held by the household sector through the end of March, but more recent data are not yet available, and the “household sector” in question here includes nonprofit organizations and, oddly enough, hedge funds.

While we won’t know for a while how much, if any, of the Fed’s monetary expansion has actually flowed through to consumers/households, let’s grant that there has been some activity there. As yet, there is reason to think households are still holding the funds as precautionary balances. Again, personal saving rates were sky high through April, and household spending was still severely depressed then.

At some point, COVID anxiety will wane, and consumers will attempt to spend cash balances that are no longer wanted. At that point, as the velocity of money will start to rise, the Fed will have to withdraw liquidity and contract the money stock to prevent excessive economic growth and inflation. Various analysts worry that this withdrawal will send interest rates soaring and kill the economy. These claims ignore the very effects that the Fed will be working to counter.

Hoarding of cash assets in late-February and throughout March by businesses and individuals drove private-sector interest rates higher and worked to depress the economy. The Fed’s countering of these pressures did not bring private-sector yields lower; they still haven’t. Rather, they merely blunted their increase. Similarly, the Fed’s actions did not prevent recession.

When these cash hoards are unwound, the effects will be the reverse of what we saw in February/March. They will put downward pressure on private-sector yields and expansive pressure on the economy. The Fed’s countering of those pressures will not bring private yields higher, nor slow the economy. As in February/March, the Fed’s actions will merely blunt the now-reversed pressures exerted by private-sector activity.

The Fed will need to be on its toes. But to paraphrase a former Fed chair, it won’t have to stop the party, merely sober it up a bit.

Is there a limit to what policy can do? Of course there is. When federal debt has risen so high that investors believe the government can no longer successfully service it, demand for federal debt will evaporate. Emerging market governments have long faced this constraint. Thankfully, the US, as a reserve currency provider, has not yet faced this constraint, at least not since the waning days of World War II. Nor have the governments of continental Europe or Japan. That does not mean the constraint does not exist.

The problem we face today is twofold. First, because the past history of debt problems among reserve currency counties is so limited, no one has a clear idea of when debt burdens will become excessive for the US (or Europe or Japan). Second, we won’t know until it is too late. Government debt auctions will continue to go fine until they don’t, at which point renewed fiscal rectitude will be too late and unable to forestall disaster. This is the reason our June 3 post advised the feds to cease further action. When remaining hardships from the COVID crisis are so localized as to be impervious to broad-based policies, and when fiscal deficits have gotten far enough out of historical range, that we are all asking what the limits are, it is time to realize that further action is unnecessary and could prove counterproductive.

Of course, the Fed can always forestall default by buying the debt. The only “limit” to what it can do is regarding the inflationary consequences. Hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic was driven by the German government’s inability to finance both reparation payments and normal government operations. The story was similar throughout Eastern Europe then, as well as in the wake of WWII, and in Zimbabwe more recently.

I’ve argued here that the Fed’s actions to date have merely accommodated precautionary demands for liquid balances by households, businesses and banks, but those demands are limited. If the Fed were to continue to inject liquidity into the system at a breakneck speed, liquidity that actually drove loan growth and money stock growth past any reasonable levels demanded by the private sector, then inflation would quickly ensue, depressed economy or not. We are not there now, and, as suggested in our previous post, if the Fed quits while it is ahead, we won’t get there.

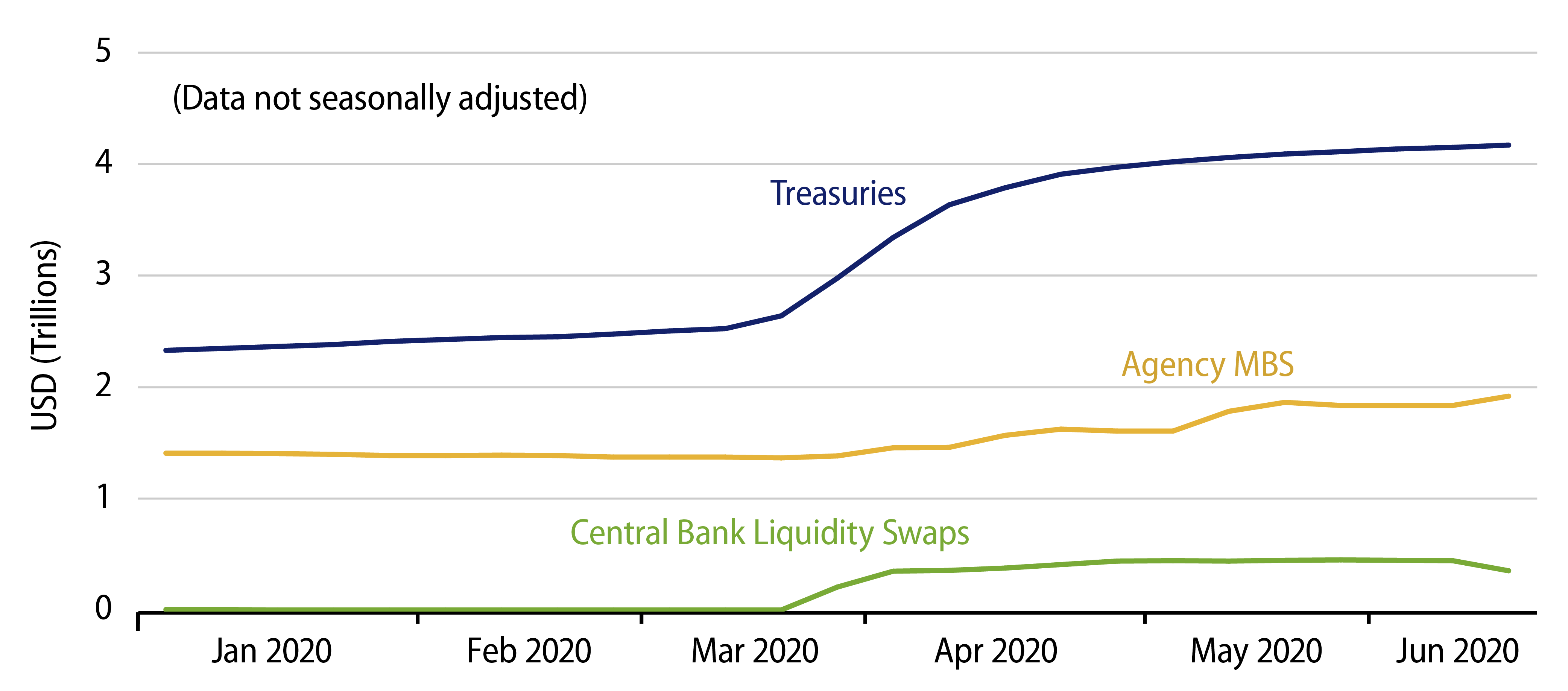

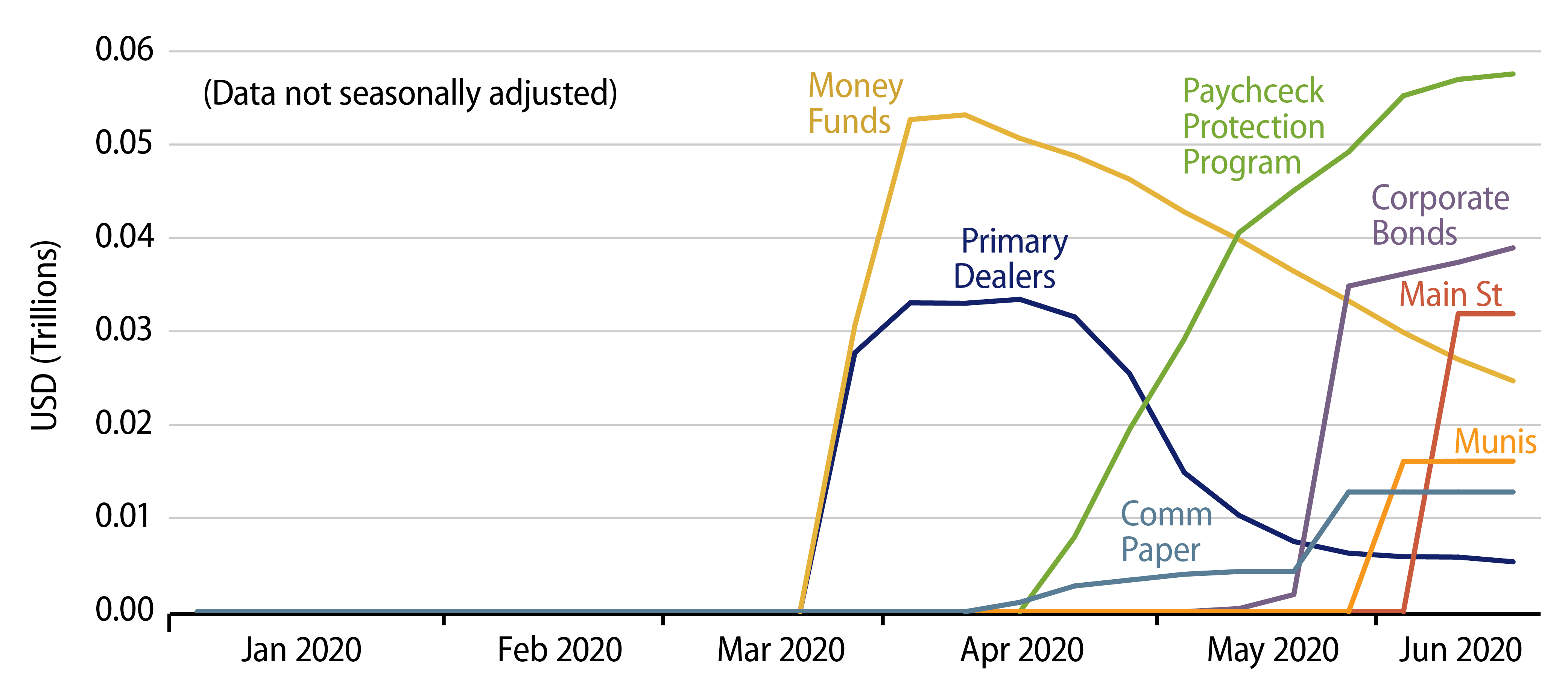

One hopeful sign is that just as businesses and banks have begun to work down the debts and cash hoards they built up during the worst of the crisis, so too the Fed has tapered its purchases of Treasuries and also worked down various “special credit facilities” that ramped up during the worst of the crisis. Exhibit 2 shows the recent slowing in Fed purchases of Treasuries and other securities. Exhibit 3 shows the ramp-up in loans to primary dealers and money funds and their contraction over the last eight weeks. PPP loans may be peaking now.

Granted, all these work-downs by the Fed, as well as those by private business and banks, are incipient, and we have a long ways to go. However, it is important to note that this process has begun. And while nothing is certain at present, it is not unreasonable to think that the unwinding process will continue to completion. A significant, sustained increase in inflation is not inevitable. As for whether the feds will go too far, much of that will depend on the pressures we exert as voters in a democracy. It is our choice.