“There is no risk-free path for monetary policy.”

~Jerome Powell, Chair of the US Federal Reserve

Quantitative easing (QE) represents monetary policy whereby a central bank purchases financial assets to stimulate economic activity via lower bond yields and increasing bank reserves. Quantitative tightening (QT) is the opposite of QE: when the economy recovers, a central bank may sell assets or gradually shrink asset holdings by not reinvesting principal repayments, also known as “runoff.”

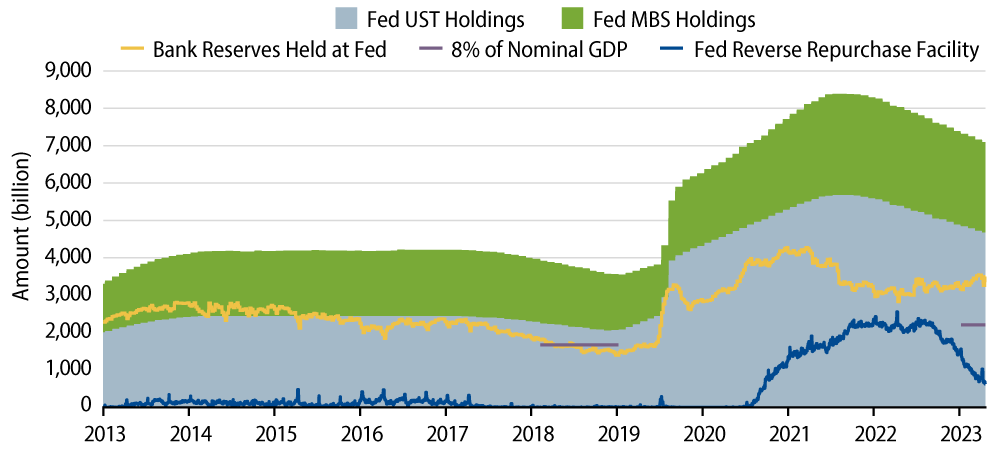

In the US, the Federal Reserve (Fed) asset holdings increased mostly through purchases of US Treasuries (USTs) and agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS) in the wake of the global financial crisis in 2008. Since then, there have been four QE programs, followed by runoff (QT) and reinvestment periods. In 2020, the Fed launched its most sizable QE program in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. After the completion of QE4, the Fed’s holdings of USTs and agency MBS peaked at $9 trillion in May 2022, when purchases ended and runoff began.

On the liability side of the Fed’s balance sheet, bank reserves have also been shrinking with QT. Bank reserves are a key signal in the management of the balance sheet and are closely monitored to ensure smooth financial market liquidity and the implementation of efficient monetary policy.

This came into focus at the December 2023 Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting. The meeting minutes stated that “several participants highlighted the decline in the Overnight Reverse Repo Program (ON RRP) and suggested that it would be appropriate for the Committee to begin to discuss the technical factors that would guide a decision to slow the pace of runoff well before such a decision was reached in order to provide appropriate advance notice to the public.”

More recently, in January 2024, Dallas Fed President Lorie Logan spoke on market monitoring and the implementation of monetary policy. Logan previously managed the Fed’s balance sheet at the New York Fed from 2012 through 2022. According to Logan, “given the rapid decline of the ON RRP. I think it’s appropriate to consider the parameters that will guide a decision to slow the runoff of our assets. In my view, we should slow the pace of runoff as ON RRP balances approach a low level. Normalizing the balance sheet more slowly can actually help get to a more efficient balance sheet in the long run by smoothing redistribution [of reserves] and reducing the likelihood that we’d have to stop prematurely.”

These comments from Logan are relevant, highlighting the Fed’s efforts in proactive communication and represent a notable shift from Chair Powell’s remarks at the December FOMC press appearance when he characterized the reserves as “ample” and said the fed funds rate and balance sheet management were on “independent tracks” with respect to the next phase of Fed policy.

The Fed’s ample reserves framework stipulates slowing down the runoff pace, then stopping the decline in the size of its balance sheet when reserve balances are somewhat above the level consistent with ample reserves, which the Fed estimates around 8% of nominal GDP. Currently, reserve balances sit at $3.5 trillion (13% of nominal GPD) and remain $1.3 trillion above the ample threshold estimates. On the other hand, QT significantly drained the ON RRP facility to $0.6 trillion from more than $2.5 trillion in 2022. Through the ON RRP, the New York Fed trading desk sells securities to banks, primary dealers and money market funds, and simultaneously agrees to repurchase the securities the next day at a set price to gauge short-term liquidity in the banking system. This allows investors to put cash in the facility and earn the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR). In this sense, the rapid decline in ON RRP signals that demand for liquidity in the system is increasing.

Logan indicated that a slower pace of runoff would also address concerns about the distribution of reserves across banks, even as the aggregate level of reserves remains abundant, especially given the current pace of runoff.

The last time the Fed slowed QT, which was after QE3, the formal policy discussion started at the January 2019 FOMC meeting and a plan was released at the March 2019 meeting, initially reducing the monthly UST runoff cap from $30 billion to $15 billion, while keeping the MBS cap at $20 billion. Implementation started in May, then in August the Fed started reinvesting all MBS principal repayments into USTs along with rolling over all UST paydowns at auctions and in September when QT ended. Using 2019 as a template, the Fed could approach current QT efforts in the same way, starting with reducing the UST QT cap from $60 billion to $30 billion, or the Fed could simply reinvest MBS paydowns into USTs, which have been running at $15 billion-$20 billion per months (well below the $35 billion cap).

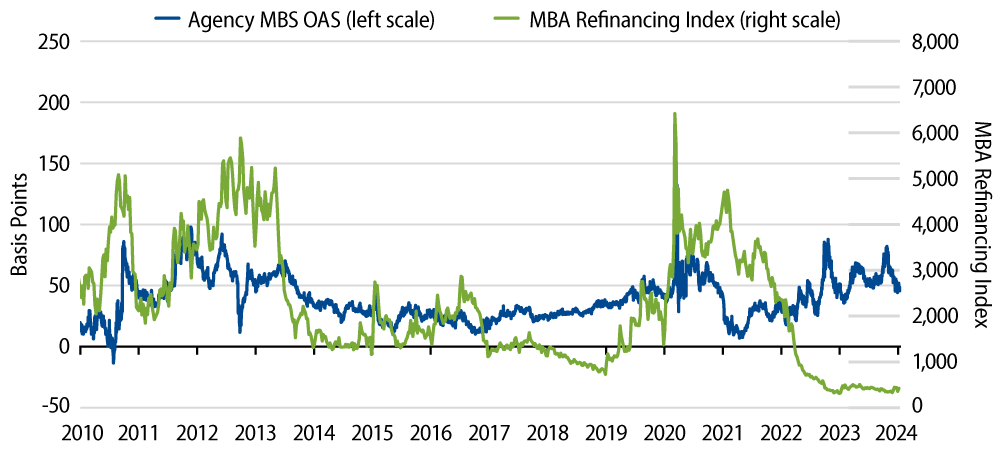

In conclusion, reducing the pace of QT removes a headwind from banks’ deposits growth, improves liquidity and market conditions, and reduces volatility. Our view is that these represent tailwinds for the agency MBS sector. In 2019, agency MBS finished the year with 61 bps of excess returns. Currently, spreads remain elevated in the historical context, while refinancing risk is structurally low, which makes for an attractive opportunity for agency MBS investments.