Headline retail sales declined by 0.3% in May, with a -0.4% revision to the April estimate. More widely watched is the control sales measure, which excludes motor vehicle, service station, building material and restaurant sales, both for the high volatility of these sectors and for the fact that they are patronized by businesses as much as by consumers. This control measure saw essentially no change in May sales (the figure was actually down 0.05%), with its April estimated level revised by -0.9%.

And we’ll add that both these measures declined in “real” terms, that is, adjusted for price increases. Of the 12 major store types for which the Census Bureau reports monthly sales data, 11 of them look to have seen declines in real terms in May, the only exception being grocery stores, where real sales had dropped substantially in the preceding three months.

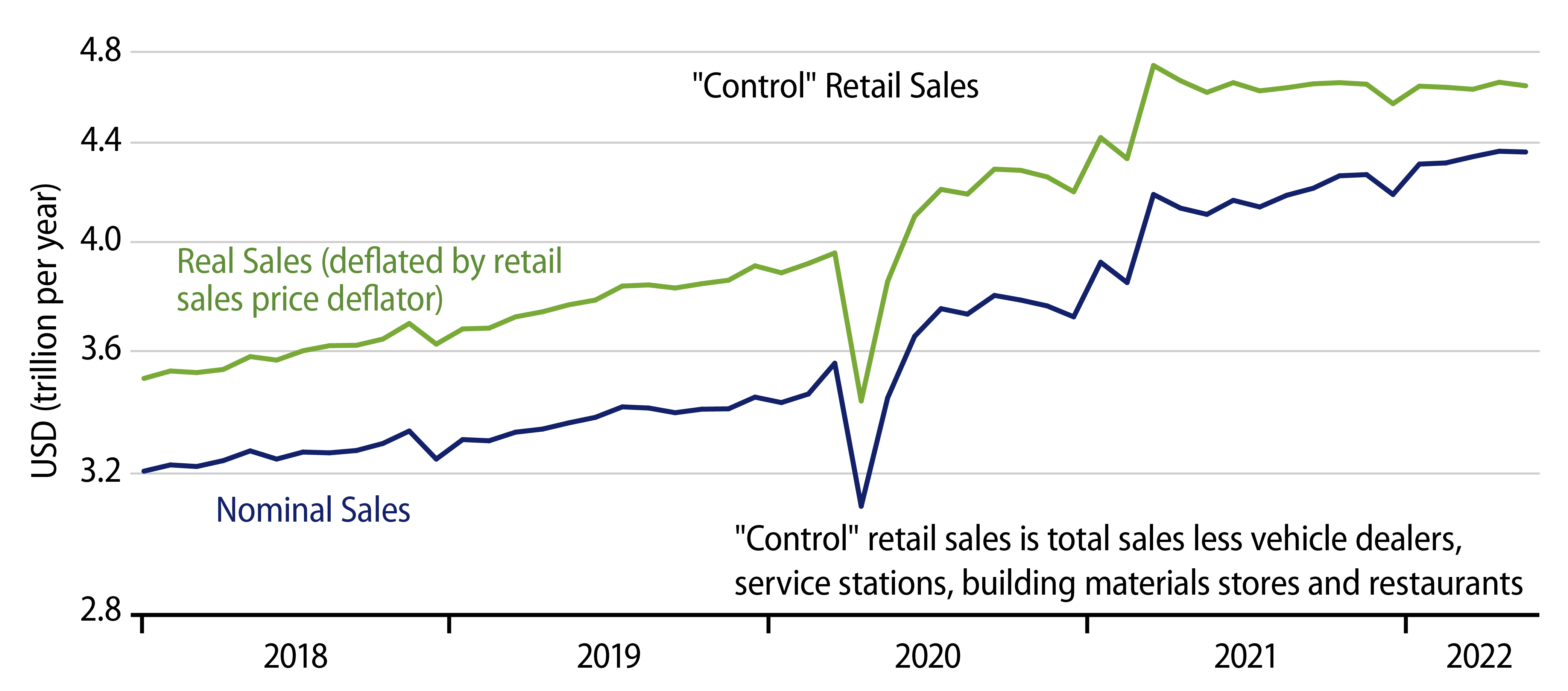

So, did today’s retail sales news show the initial effects of Federal Reserve (Fed) rate hikes on consumer activity? Not really. Rather, our take is that today’s news is merely a continuation of the flat-to-declining trend for real retail sales sustained for the last 14 months. A month ago, while market response was generally gushing with respect to the sales gains announced for April, our take was that those gains did not really move the needle in the face of the net declines of the previous 12 months.

Well, with today’s news, more than half of the already insubstantial sales gains for April were revised away, and, again, real sales generally declined further in May. As you can see in the accompanying chart, with respect to real sales, today’s news is clearly of a piece with what we have been seeing since March 2021.

Of course, the general declines in real retail sales--thus in real consumer spending on merchandise--have been offset by relatively good gains in consumer spending on services, as various service sectors continue to reopen from Covid restrictions. We’ve already asserted that the flat-to-down trends for retail sales do not appear to be due to Fed policy moves. Along those lines, services spending is not very interest-sensitive and so is not going to be an “early responder” to interest rate moves.

Rather, when and as the Fed’s moves start to bite, we are likely to see it first in homebuilding activity and, possibly, business investment, whence it will spread to job growth and then to services consumption. We may indeed see goods consumption (and retail sales) weaken further, but, again, such effects are not in evidence as yet.

Finally, as discussed in last week’s post, we had been looking for declining goods demand and rising goods supply to soften goods-sector pricing, and there was little evidence of that within the May CPI report, after March and April inflation reports had been more encouraging on that score. We would expect the continuing softness in real merchandise sales to exert downward pressure on prices there in months to come.