Last week the US again increased tariffs on certain Chinese imports. This was the third round of tariffs on Chinese imports in the last 18 months, following announcements in 2018 of 20% tariffs on Chinese washing machines and solar panels, and 10% tariffs on $200 billion of select imports. The prospect of higher tariffs has once again raised concerns about their impact on inflation.

Given that the initial round of Chinese tariffs is now over a year old, the 2018 experience can inform an assessment of the likely impacts of the new tariffs. The straightforward conclusions are that the new tariffs will likely raise consumer prices, but the effects are unlikely to be persistent. The tariffs will also likely weigh on demand, but will have almost no impact on Fed policy. Taken together this suggests the inflationary impacts of tariffs are not particularly worrisome.

These conclusions are based on four simple observations from an analysis of how prices and quantities of “major appliances” responded to the 2018 tariffs on washing machines:

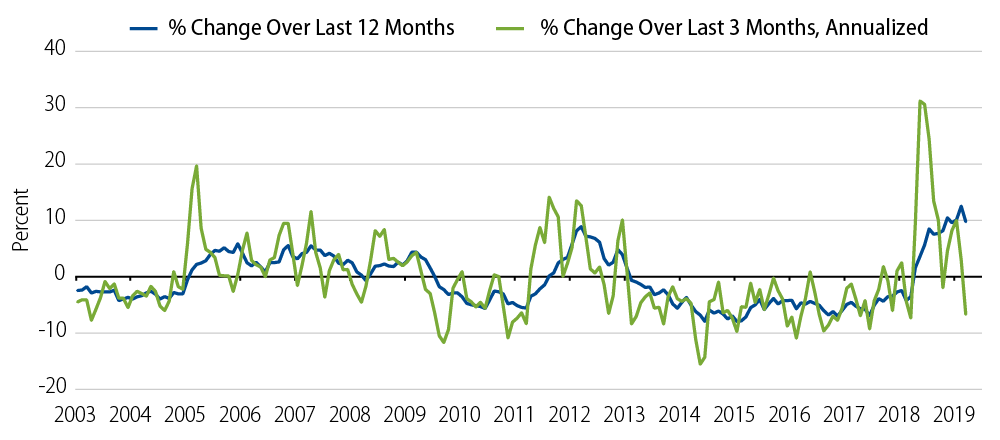

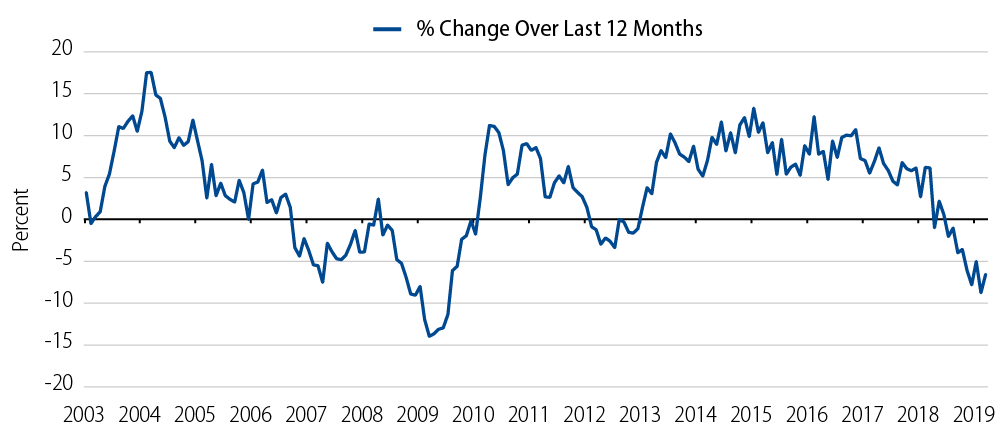

- Tariffs caused consumer prices to rise, with the effects appearing quickly after tariffs were imposed. Washing machine tariffs were announced in January 2018. After 12 months, the prices of major appliances in the Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) index had increased by 12%, with over two-thirds of that increase happening in the first six months following the announcement. Also of note is that the pass-through of tariffs to consumer prices is reasonably high, especially considering that washing machines are only part of that particular PCE category. This is consistent with recent academic research that analyzes price increases at a more granular level and concluded tariff pass-through was almost 100%.

- The tariff impact was short-lived, as inflation quickly fell back to pre-tariff levels. Following the sharp increase post tariffs, subsequent price increases have been modest. In fact, prices declined outright in March 2019 (the last month of available data), and in doing so returned to the pre-tariff pattern, which saw six straight years of price declines. The lack of follow-through on price inflation should not be all that surprising, as the tariff increases have not been repeated and tariffs have weighed on demand, which we turn to next.

If the assessment above is correct insofar as what it implies for the new tariffs and inflation, there is unlikely to be much, if any, direct impact on the bond market. The bond market will correctly look through any transient increase in inflation and focus on the lack of persistent effects. Any softening of demand may actually weigh on bond yields, and at least would prevent an increase. The more important considerations for the bond market will be any indirect impacts of tariffs, which could stem from changes in financial conditions or changes to the global growth outlook.