Last year, the Fed spent a lot of time and effort arguing that it needed to raise interest rates to get them back to “neutral” levels, to where they were no longer stimulating the economy. While stock market and global growth concerns have put this issue on the back burner, it is sure to resurface again soon. We believe the neutral rate level is a much more elusive concept than the Fed lets on and that the evidence suggests we are already at or above neutral rates.

What does the Fed mean when it says rates are still stimulative? It means rate levels are directly stimulating faster consumer and business spending, right? No, that is not what it means. A decline in interest rates can stimulate private spending, but only for a while. Economists typically estimate the lagged effects of rate declines as lasting from six months to two years. The last Fed rate cut was in 2008, and T-bond yields hit their lows in 2009. The stimulative effects of yields on spending growth ran out eight years ago or more.

Instead, what the Fed means is that rates are below their long-run “equilibrium”—or sustainable—levels. As an economy recovers from a recession or responds to a bout of stimulative policy, rising income and spending levels impart upward pressure on interest rates. The Fed—or any central bank—can counter that pressure and hold yields down only by providing more stimulus: pumping still more money and credit into the system to offset the internal pressures that would otherwise be raising yields.

However, such stimulus imposes ever-increasing strains on an economy. Spending is accelerated faster and faster, creating even more upward pressure on yields, thus requiring still more policy stimulus to prevent rates from rising. In this pressure-cooker environment, internal strains accumulate until the economy explodes, much as actually happened in the US in the 1970s.

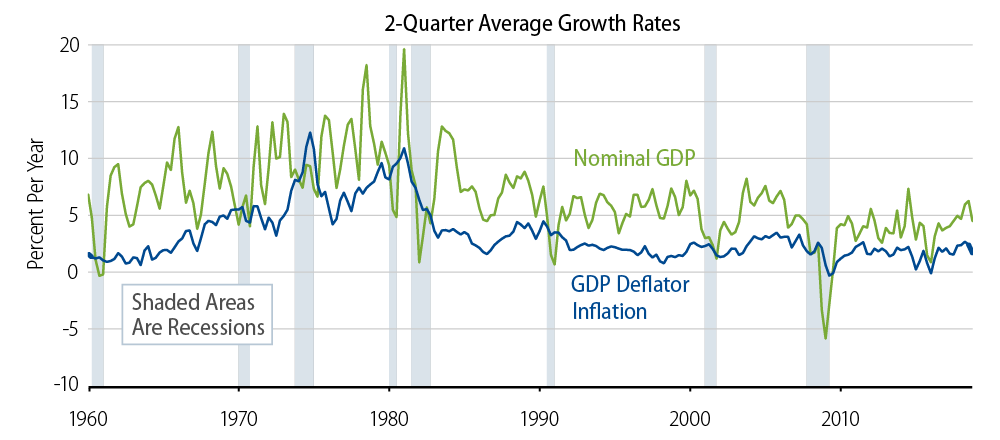

The US economy currently exhibits no sign of such stresses. Bond yields have remained essentially flat despite years of supposedly below-neutral short rates and even four years of hikes in short rates. Bond yields have also held stable despite the fact that the Fed ceased injecting liquidity into the system five years ago. In fact, the Fed has been steadily withdrawing liquidity ever since then. Inflation remains stable despite widespread expectations—even hopes—for an acceleration. Nominal GDP (spending) growth itself has remained stable at a very low 4% to 5% rate throughout the 10 years of this expansion.

If the Fed were really below neutral, all these economic indicators would be showing ever-accelerating growth, and term yields would have started shooting up as soon as liquidity injections ceased. But no!

To repeat, the abiding belief that interest rates are below neutral or below normal is simply at odds with experience. It could well be that short rates have already peaked for this cycle and will be sustained at lower levels in the future.