In a few months the US presidential election will move to the center of attention. Federal Reserve (Fed) officials may welcome the shift in focus, as they and their policies have been under intense scrutiny for longer than has been comfortable. In its ideal world, the Fed will slip out of the harsh glare of the spotlight at a time when the US economy is performing near the Fed’s targets. The unemployment rate is expected to remain around 4%, and inflation is expected to be approaching 2%, although the pace of the Fed’s approach continues to be a subject of debate and uncertainty.

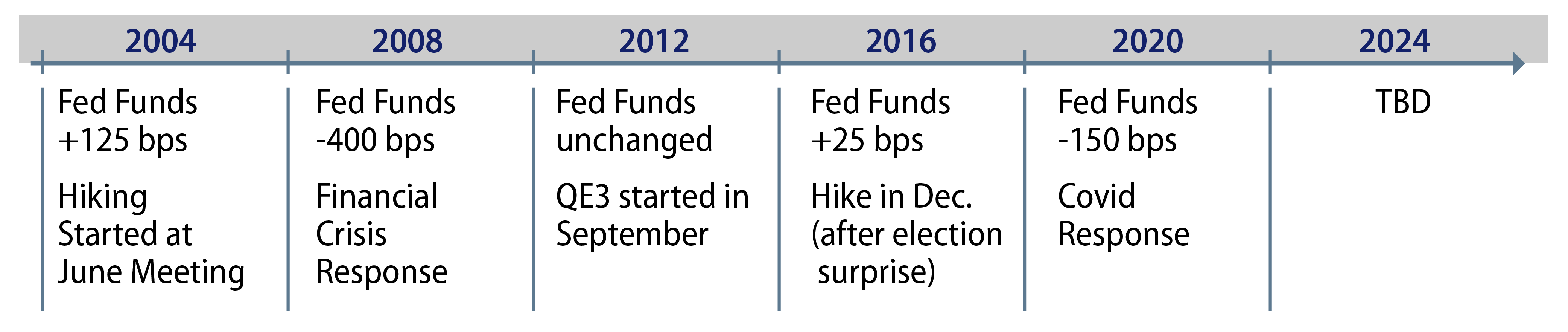

Slipping out of the spotlight does not necessarily mean being inactive, however, as the Fed must continue to set monetary policy in a way it deems most appropriate. Events have a way of requiring the Fed to take action, regardless of the electoral calendar and despite the public profile that Fed officials may prefer. Indeed, the Fed has been active in every election year since 2004. A review of this recent history suggests a few observations about how the Fed is likely to behave in an election year, and what types of events may elicit a monetary policy response before November. Of course, the candidates themselves may also attempt to drag the Fed back into the spotlight.

Observation 1: The Fed will not hesitate to respond to a large shock.

The most significant events in financial markets over the past two decades occurred in election years: the global financial crisis of 2008 and the Covid pandemic of 2020. Obviously, the fact that they occurred in election years had nothing directly to do with the events themselves. The fact that these were election years also had no apparent bearing on the Fed’s responses. The Fed eased policy aggressively throughout 2008 and showed no sign of letting up on either side of the election. To the contrary, at the Fed’s October 2008 meeting, which took place less than two weeks ahead of the November 8 election, the Fed cut interest rates and opened swap lines with many central banks. Over subsequent weeks the Fed initiated programs to purchase asset-backed securities and agency obligations, before lowering interest rates again at its December meeting.

In 2020, the Fed’s response to Covid was no less dramatic. Early in March, the Fed lowered interest rates to zero in two intermeeting moves. It then commenced a very aggressive bond buying program, which reached a peak of $80 billion per day by late March, as well as a slew of programs to support credit markets. The Fed kept up the stimulus throughout the remainder of the year, even as the most acute financial market disruptions passed rather quickly. In August, the Fed announced a new framework that committed policymakers to maintaining an accommodative stance even as the labor market recovered. While this framework would eventually be made irrelevant by the inflation surprises of 2021 and 2022, it’s important to remember that, at the time of its unveiling, which was only a few months before the election, the Fed intended it to signal further accommodation.

The Fed’s actions in 2008 and 2020 leave no room for doubt: if significant policy action is required, the Fed will deliver it, regardless of whether or not it is an election year.

Observation 2: The Fed may respond to a change in fiscal policy expectations after the election, but not before.

Economic policy proposals will not be the most contested part of this year’s election. The candidates’ economic records will be scrutinized, of course, but the differences in policy proposals are small and unlikely to be decisive. This will not resemble, say, the election of 1992, when voter preferences were swayed by the debates on George Bush’s tax increases, Bill Clinton’s health care proposals and Ross Perot’s objections to free trade. At this early stage, it appears the 2024 election is more likely to be decided on social issues, personalities and, perhaps, issues that have only an indirect economic impact, such as immigration and foreign policy.

Still, all elections have consequences, and inevitably there will be some for economic policy. The most immediate has to do with the expiration of individual tax cuts at the end of 2025. (As a reminder, the 2017 corporate tax cut is permanent, but the individual tax cut will sunset next year. This was done to reduce costs within the 10-year budget window.) The party that controls the White House will approach the tax cut expiration in the expected way: A Democrat will seek to end the tax cuts for the top brackets, while a Republican will seek to extend all the tax cuts. As to whether they are successful, control of Congress will obviously matter, as will the proposals for offsets (or lack of offsets) on the spending side.

For the purposes of this note, the question is whether an anticipation of changes in fiscal policies could influence Fed actions this year. The answer, in our view, is clearly not before November, but potentially after. The Fed would be loath to act preemptively on such an issue. Elections are simply too uncertain. Moreover, the Fed typically prefers to avoid debates about the mix of revenues and spending, which it views as primarily political issues rather than economic ones.

After the election the Fed might be more willing to offset changes in fiscal policy. The Fed’s reaction to the 2016 election is informative in this regard. The surprise election of Donald Trump caused a sharp reassessment of fiscal policy expectations. In the weeks following the 2016 election the yield on 10-year US Treasury bonds rose by 0.6%, in part due to anticipation of large tax cuts along with other pro-growth policies. The Fed then hiked at its December meeting, after having been on hold for the previous 12 months. While it was never said explicitly, it seems likely that the Fed decision was, at least in part, intended to offset some of the anticipated stimulus from tax cuts. In a similar fashion, should there be changes in expectations for fiscal policies for 2025 and beyond, the Fed would likely respond in the normal way. But it will almost certainly wait until after the election to do so.

Observation 3: All else equal, the Fed may prefer to initiate policy actions in the summer to avoid any appearance of unduly influencing the election.

This last observation is admittedly more subjective than the others. Fed officials are aware there is an election in November. It’s uncontroversial to assume they prefer avoiding any appearance of undue influence. And while they will strenuously deny charges of meddling in any case, some distance between an action and the election will make such denials more believable. As a result, they may want to avoid starting the cutting cycle at either the September or the November meeting. A start in September risks the appearance of priming the economy in order to help the incumbent, while a start in November risks the appearance of not doing enough to support the economy in order to help the challenger. From this perspective, the summer may be a less controversial time to start a cutting cycle. Of course, any cuts are conditional on inflation continuing to make progress back toward the Fed’s target of 2%, which we think it will.

It is notable that former Fed Chair Alan Greenspan started the 2004 hiking cycle at the June meeting of that year. That hiking cycle then proceeded at a pace of 0.25% every meeting, including the meetings immediately before and after the election. To be sure, the meeting transcripts do not mention the election, nor has Greenspan subsequently said that the timing of the election was a consideration. Nevertheless, Greenspan was famously attuned to the political climate and adept at navigating the various political considerations. A similar calculus to the one described here potentially influenced Greenspan’s decision to act in the summer, rather than in the fall. Should the economy proceed as expected this year, Jerome Powell could do worse than to follow Greenspan’s lead and start the cutting cycle in the summer.

The Candidates

The presidential candidates could attempt to make monetary policy an election issue. Donald Trump was not shy about commenting on monetary policy during the 2016 election season. In May of that year he proclaimed himself to be a “low-interest-rate person.” And then, somewhat confusingly, in September he accused the Fed of keeping rates inappropriately low in order to boost Hillary Clinton’s chances. As President in 2018 he returned to being a low-interest-rate person and was very critical of the Fed’s hikes in that year. It would not be a surprise if Trump were to revisit similar themes in the coming months. That said, it’s not clear whether any such comments from Trump would affect Fed officials. Chair Powell in particular has some practice in deflecting Trump’s criticisms, and he could easily revert to his standoffish talking points from 2018. Accordingly, we don’t expect what the candidates say in the next few months to matter all that much, if at all.

In conclusion, our discussion here may have an implication for the Fed’s willingness to surprise markets in the coming months. On many occasions over the past few years Fed surprises have been a source of volatility for financial markets. In many instances surprising the market was likely the Fed’s intent, as officials saw it as a necessary part of their fight against inflation. Today the inflation threat is much diminished, and so too is the need for the Fed to exert a corrective force on market pricing. Moreover, a lower profile, and therefore fewer surprises, may be especially welcome in an election year. Maintaining a steady and constant forecast works in that direction as well.

At the end of its meeting today the Fed left its forecast for interest rates unchanged at three cuts this year. In his post-meeting press conference Powell repeatedly mentioned not overreacting to “bumps” in the road to lower inflation. Both the unchanged forecast and Powell’s steadiness seem consistent with an underlying desire to make comparatively fewer waves in this election year.