Since the outbreak of COVID-19, the UK economy has been subject to the same drivers as have other major economies, with restrictions initially leading into a significant drop in economic activity. More recently, powerful reopening forces saw demand recover and inflation surge.

The Bank of England (BoE) loosened monetary policy rapidly as the pandemic took hold and fiscal policy also provided strong support. As the recovery progressed, the central bank has sought to counteract significantly above-target inflation by normalizing monetary policy at a relatively rapid pace.

Here we provide additional detail on the current economic outlook for the UK and our thoughts on the expected future path of monetary policy.

A Recap

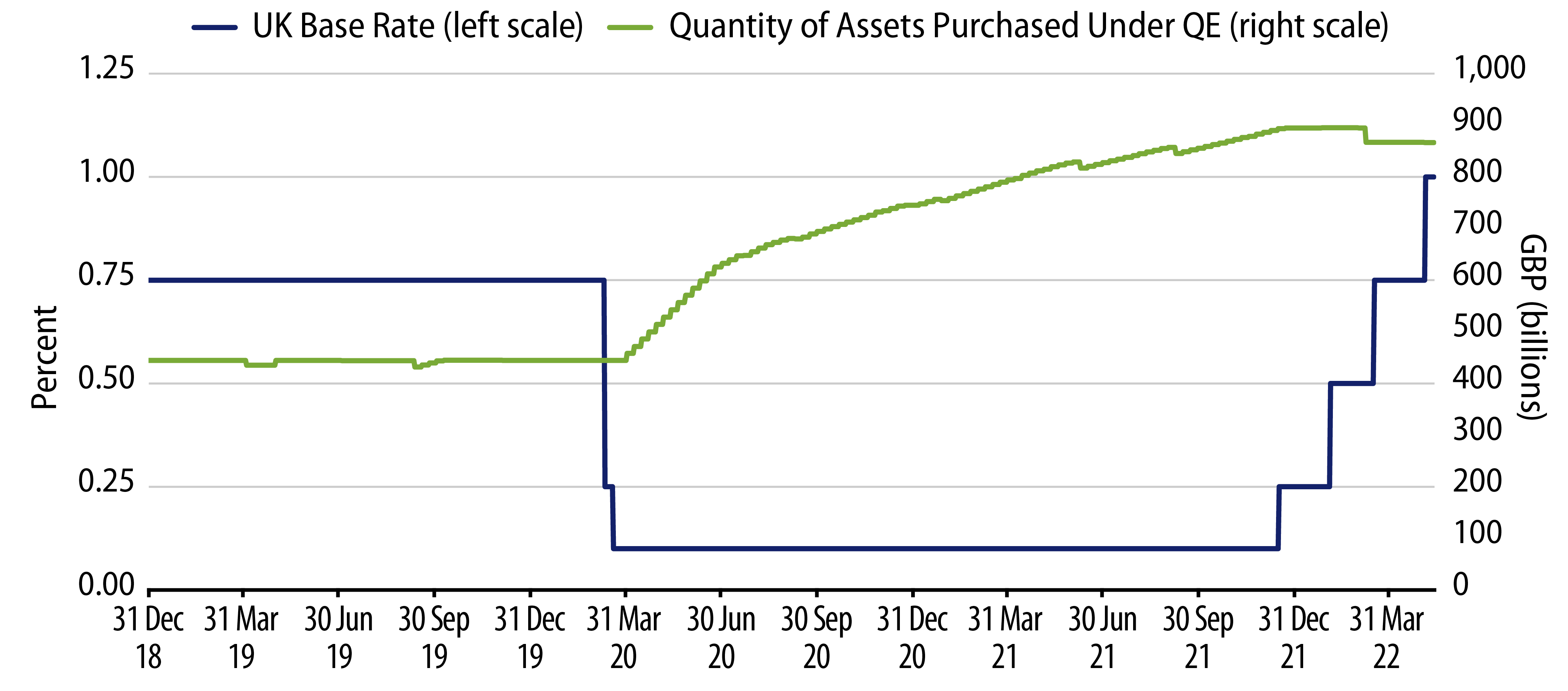

The pandemic’s impact on the UK was severe. In 2020, the economy contracted by 9.3%—the largest decline among G-7 countries. The BoE cut its policy rate aggressively in March 2020 and increased the size of its quantitative easing (QE) programme (Exhibit 1) to combat the economic impact of the pandemic.

The UK government also implemented extraordinary fiscal support including the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme, which provided grants to employers so that they could retain and continue to pay employees.

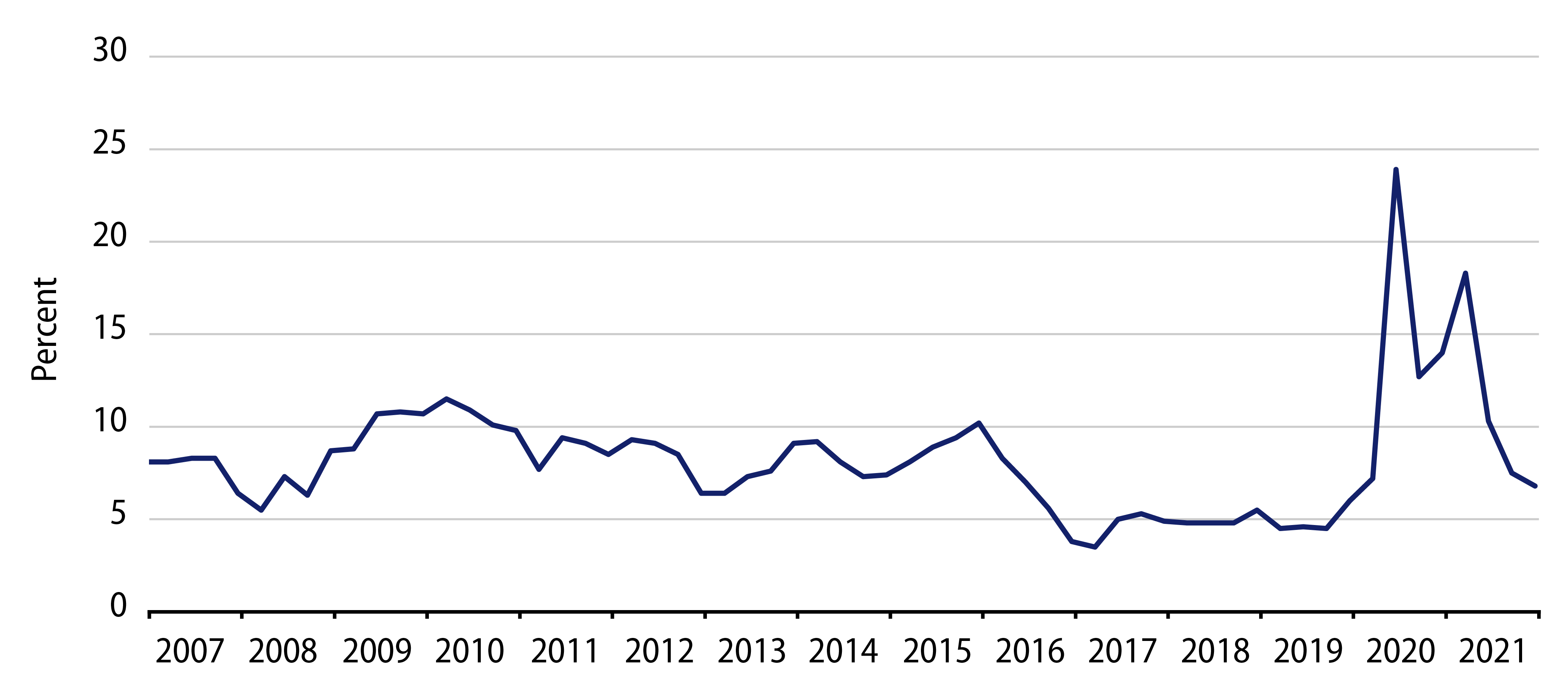

Elevated household savings (Exhibit 2) were a key factor behind the strong recovery. For those under continued employment or furlough, savings built markedly because typical spending fell materially (e.g., on travel or hospitality). As restrictions were loosened and eventually removed, strong pent-up demand combined with robust personal finances to drive a sharp rebound in spending.

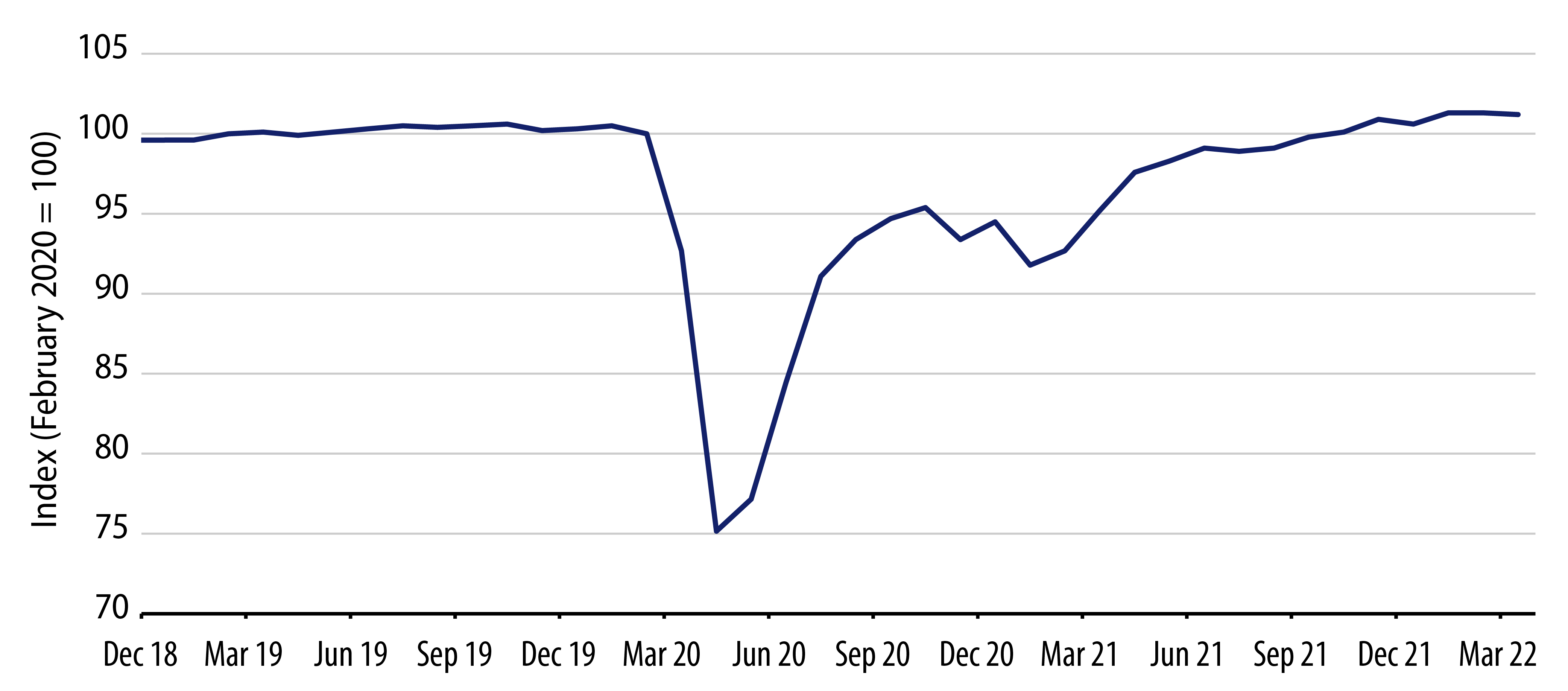

By the fourth quarter of 2021, GDP had largely returned to its pre-pandemic level (see Exhibit 3—growth in 2021 was 7.3%, the highest among the G-7); inflation was continuing to rise (Exhibit 4), and the labour market remained tight. At that point, the BoE’s Asset Purchase Programme was ending and the BoE began to normalize monetary policy rates, citing the risk of second-round effects whereby higher inflation expectations could become embedded and feed into higher wage growth. Since then, further hikes have taken the base rate to 1%, above its pre-pandemic level (Exhibit 1).

Where We Stand

Inflation has continued to surprise to the upside, reaching 9% year-over-year (YoY) in April, and the labour market has tightened further. On this basis, the market’s pricing for the BoE to raise its base rate above 2% by the end of this year has some logic. However, we don’t believe this properly accounts for a shift in the economic outlook, nor recent guidance from the BoE.

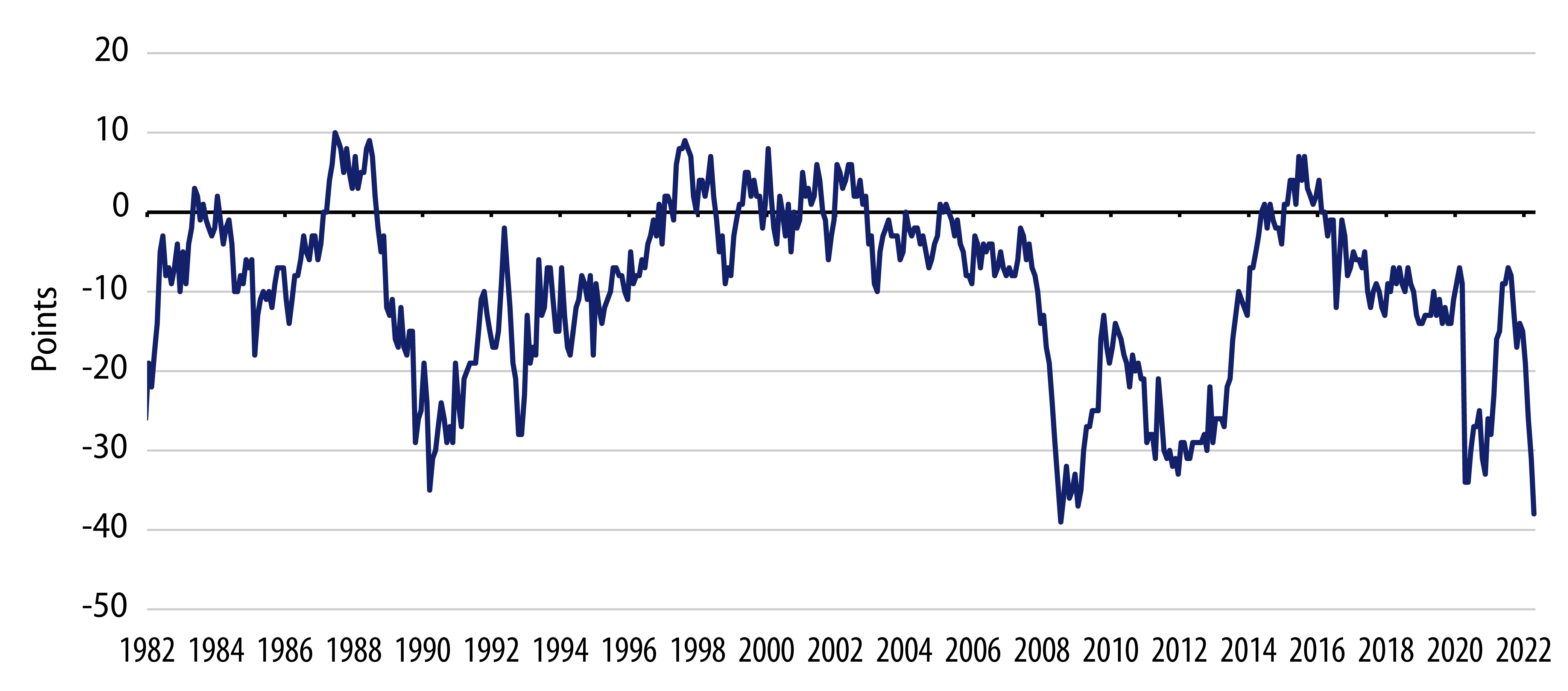

In April, household energy prices jumped significantly due to an increase of the regulator’s price cap. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine further exacerbated price pressures. At the same time, national insurance tax contributions increased. With such an acute squeeze in real disposable incomes, higher interest rates and elevated uncertainty, it is unsurprising that consumer confidence surveys have shown sharp declines (Exhibit 5). Evidence of a cooling economy has been seen in lower retail sales and a surprise economic contraction in March.

At its recent monetary policy meeting, the BoE expressed concern over declining real disposable incomes and their dampening pressure on prices and consumption, revising growth projections downwards.

The Likely Path Forward

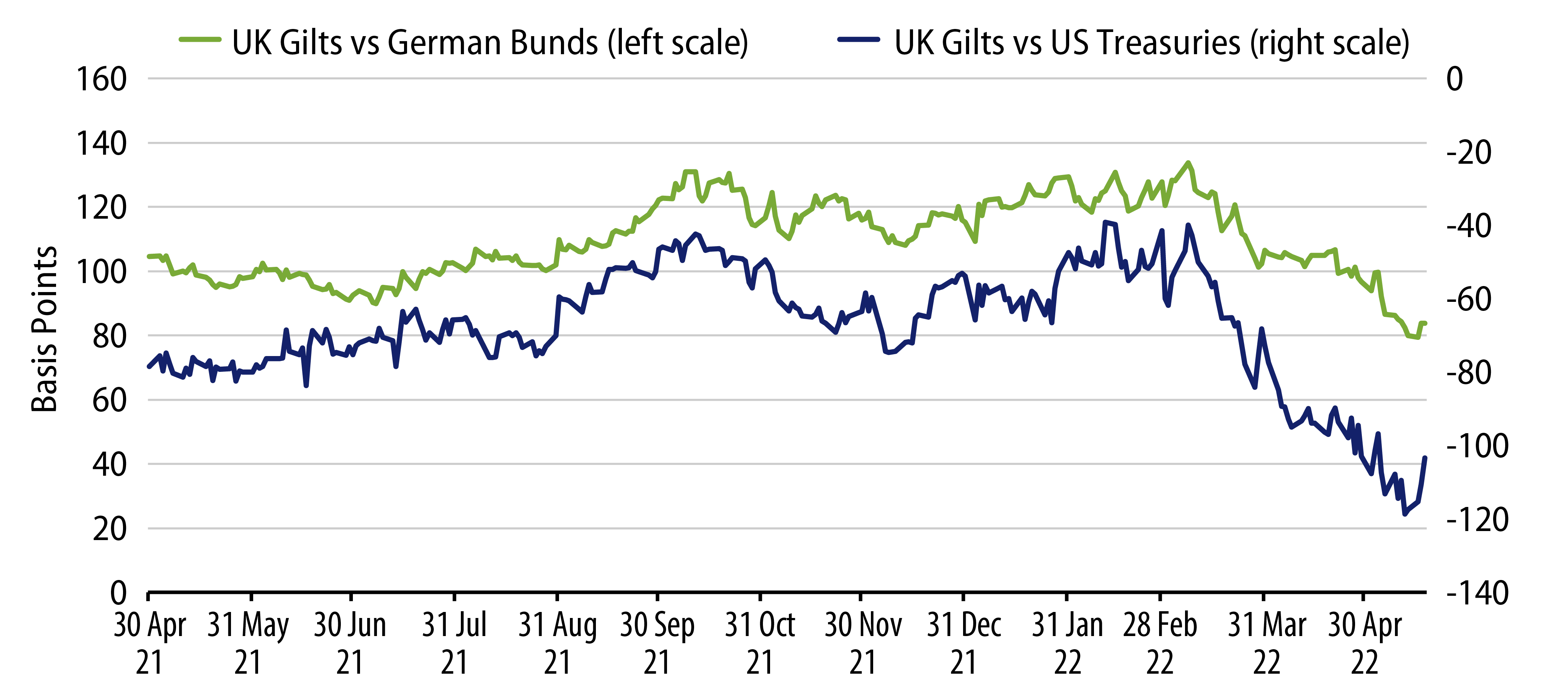

In the second half of last year, global portfolios were underweight UK duration, as we expected a strong rebound in growth and believed that this would allow the BoE to begin to normalize monetary policy. This indeed led to an underperformance of gilts (Exhibit 6). During the first quarter of this year we took the opposite view, namely that the market was pricing in too much tightening given the real disposable income squeeze described, and we initiated an overweight to UK duration. Since then, gilts have outperformed strongly.

The market continues to price more BoE rate hikes than we expect, but we recognize that this is to some extent conditional on the degree of normalization from other major central banks, including the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank. We believe that market-implied rate hikes in both the US and eurozone are also excessive, and feel that pressure on real disposable incomes and spending could come into greater focus in these regions as it has done in the UK, potentially leading to a further recalibration lower of growth and market rate expectations globally.