The De-Dollarization Debate: More Bark Than Bite

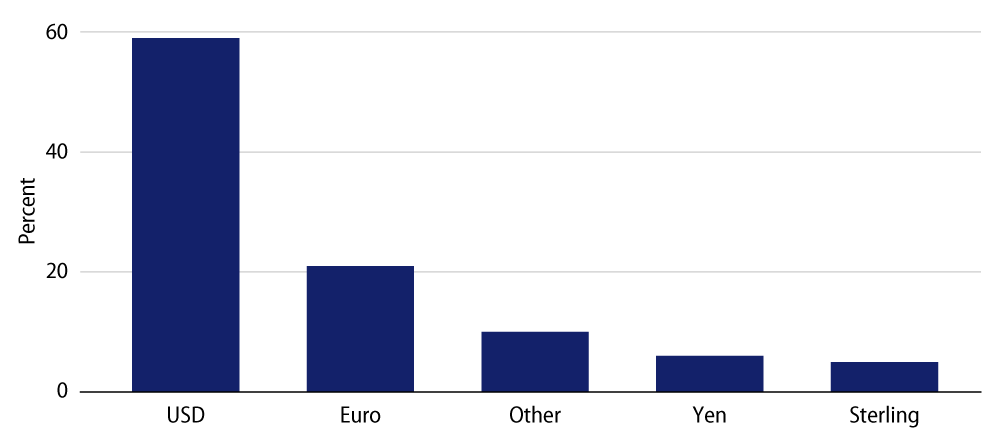

The IMF’s latest global foreign-exchange reserves data shows that the USD’s share has fallen below 60%, extending a two-decade decline from its high of 70% in the late 1990s. Isn’t this proof that de-dollarization is well underway?

Not necessarily. The decline of the USD as the world’s main reserve currency can be explained by the formation of the eurozone (paved by the Maastricht Treaty in 1992), China’s entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001 and de-dollarization initiatives introduced over the years by a number of countries (principally in the emerging world) in an attempt to reduce USD dependency, diversify reserves, evade US sanctions or take a (geo)political stance against “the West.”

It’s important to bear in mind that countries hold reserves for a number of reasons: to protect themselves against economic shocks, to influence the value of their own currency, to cover import costs and to service debt. For these reasons, the key attributes that countries look for in a reserve currency include economic strength and stability, predictable policies, sound governance and financial depth (i.e., deep, liquid, transparent and open capital markets1). The US holds sway in all of these areas (relative to the rest of the world) which explains why de-dollarization or the shift to an alternative reserve currency still has a long way to go.

Network Effects of the US Dollar Are Unmatched

Several countries have recently advocated for the end of the USD in global transactions. Is the USD in jeopardy of losing its status as the world’s preferred currency?

No. Whether we look at the USD’s outsized role in international transactions (i.e., activity in the foreign exchange spot, forward and swap markets based on leg of a transaction), how much of global trade is invoiced in USD (four times the US’ share of world trade), the percentage of cross-border lending activity denominated in USD, the amount of international debt issued in USD or the amount of USD-based volume across the SWIFT network2, the dominant position of the US appears to be solid. This is mainly attributable to the standing of the US as the world’s largest economy, the independence of its legal system and the credibility of the Federal Reserve.

Looking at the USD Through the Lens of History

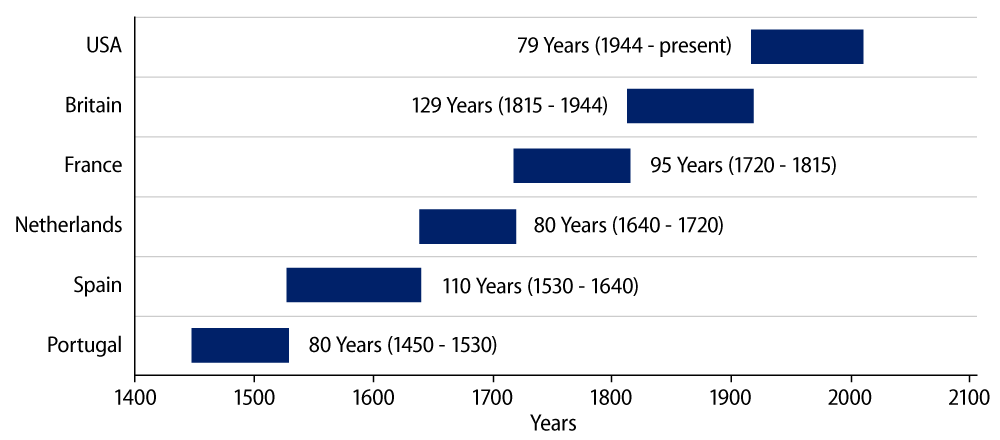

History shows that the transition of each global reserve currency took place after approximately a century and typically occurred during a period of major economic and political upheaval (Exhibit 3). Is the US poised to meet the same fate?

Only time will tell. There’s no question that past empires have collapsed due to an over-reach of power leading to revolution, war and economic ruin. On the US, plenty of ink has been spilled over its waning global leadership. Warnings about the sizable US deficits, high debt levels and political instability may have some merit, but the US has been able to demonstrate remarkable economic and political resiliency since the end of the post-World War era. Academics have attributed this to the country’s military potential, political structure and culture, geographic size and location, and economic and technological resources. But all arrows point back to one other key factor: the role of the USD which allows the US to borrow money easily, manage the impact of financial crises and levy sanctions against adversarial countries. The euro, the Chinese yuan, special drawing rights and even digital currencies have been offered up as possible alternatives to the USD. However, to date all have fallen short of pundits’ expectations, and none of these are viewed as safe-haven assets during periods of global turmoil. In short, it’s very difficult to see the USD losing its “exorbitant privilege” anytime soon3.

ENDNOTES