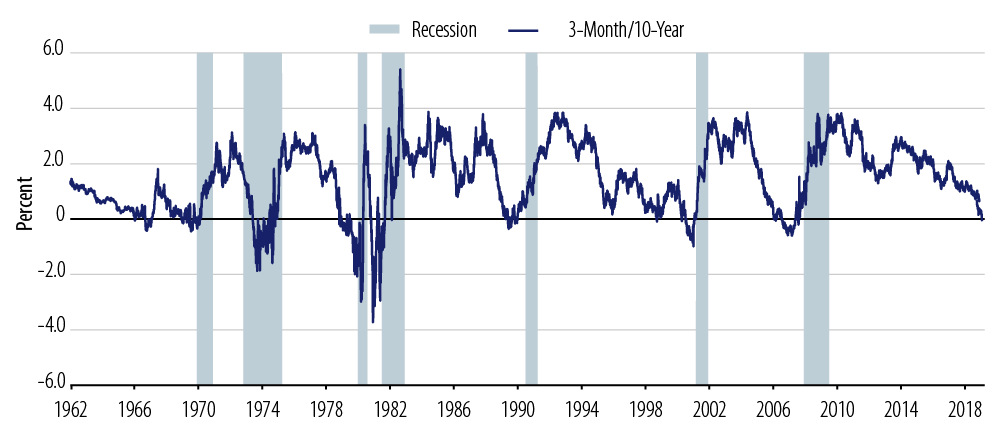

Discussions about an inverted yield curve—and whether it portends a recession—are back in the spotlight. Of particular interest is the spread between 3-month T-bills and 10-year USTs, as this curve went negative on March 23. Because the last six out of seven US recessions have been preceded by an inversion between these two maturities (Exhibit 1), the question now is whether another recession will surface in the next six to 18 months.

Here we examine the powerful predictive history of the 3m/10yr curve and highlight why there are discrepancies between what this curve and other curves tell us. We also describe the differences in the financial landscape since the great financial crisis (GFC) and why this may prompt a different economic outcome this time around.

So why is the shape of the 3m/10yr curve so important? In short, the 3m rate is a proxy for the rate at which financial institutions borrow while the 10yr rate is that at which they can earn/lend/extend credit. If this spread is negative, lending or credit creation shrinks, which leads to nominal growth falling because it diminishes the incentive for financial institutions to lend for longer-term investments that generate growth.

A Tale of Two Curves

Now, if you look at the 5yr/30yr curve as a basis for assessing long-term inflation expectations, which have a high correlation with 30yr bond yields and the commensurate Fed reaction function (high correlation with 5yr UST yields), then the story is a bit different. The 5yr/30yr curve began flattening aggressively in late 3Q17 and continued until its low point of 19 bps in July 2018 before steadily steepening and reaching its current wide level of 67 bps. This steepening occurred at the same time the 3m/10yr was flattening (Exhibit 2). This is true not only in spot space, but also in forward space, suggesting that the Fed may have been preemptive in its dovishness and is engineering a soft landing to prevent a recession.

Changes in the Financial Landscape

A lot has changed in the financial system since the GFC that suggests the message from inverted yield curves is not the same as it’s been in the past. First, the risks of a “bank run” type of funding freeze are much lower since the GFC. Banks are not as dependent on retail funding (customer deposits) as they were prior to the crisis. For this reason, higher short rates may lessen the effect to constrain lending and create tighter financial conditions. Regulatory changes since the GFC also have made bank funding more stable and central banks are there to provide liquidity and curtail any stoppage of funding. This was reinforced last November by Fed Chair Jerome Powell who said, “after 10 years of concentrated effort in the public and private sectors, the system is now much stronger, with greater capacity to function effectively in stressful times.”

Second, credit risk or debt in the system increasingly resides on sovereign balance sheets. Private sector debt levels remain below the levels seen prior to the GFC. Given the health of the consumer and the manageable debt levels in the corporate sector, levels don’t suggest to us that the likelihood of a severe default cycle is now higher than before the crisis. Additionally, we don’t see signs of excesses in the economy that need to be unwound as was the case in previous boom-bust cycles. In fact, GDP is still struggling to return to the pre-GFC trend.

Finally, the financial landscape is now different because central banks in advanced economies are utilizing additional monetary policy tools. There’s also the expectation that central banks will remain accommodative and err on the dovish side, as evidenced by the recent pivots by both the ECB and the Fed. This was explicitly reinforced by Powell in March when he said, “My colleagues and I have one overarching goal: to sustain the economic expansion.”

The Bottom Line

While the 3m/10yr curve historically has been a powerful leading indicator of growth and inflation in the US, we think it deserves closer scrutiny given the changes in the financial backdrop. If that portion of the curve remains inverted for a protracted period then there should be greater cause for concern. But, for now, if growth is resilient and central banks remain supportive then this inversion could just be sounding a false alarm.