Dim sum (点心) is a popular Chinese cuisine comprising a wide sampling of small dishes served successively. Tracing its roots to southern China, dim sum literally means “touch the heart” in the Cantonese dialect. Originally conceived as affordable snacks to complement tea drinking for road travelers and rural laborers, the menu expanded quickly to cater to the palate of patrons from different provincial regions. With the passage of time, dim sum underwent a makeover to become a distinctive form of culinary art, with its presence felt across the globe.

Drawing parallels between dining and investing, there are some interesting observations when juxtaposing the transformation of dim sum with the development of emerging markets (EM) investing.

From Hors D’oeuvres to Entrées

US dollar-denominated bonds issued by developing countries—mostly in Latin America—under the Brady Plan three decades ago marked the first foray into EM debt. At that time, proprietary desks of international banks were the dominant players. Where real money was involved, the allocations to EM were in the context of developed markets (DM) strategies, and therefore highly opportunistic in nature. Indeed, the degree of investor interest was subject to speculative boom-bust episodes, such as Mexico’s Tequila Crisis (1994), the Asian Financial Crisis (1997-1998) and the Russian Default (1998).

Nevertheless, Brady bonds did have a pivotal impact in spawning the JPMorgan family of EM indices, beginning with USD-denominated sovereign securities in the 1990s. Over the next decade, the growth leadership of large EM countries helped forge the notion of EM as an asset class. Importantly, the increase in EM issuance registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) serves to stoke crossover demand, as these bonds are included in select DM benchmarks. Additionally, in recent years, negative yields in DM bonds have induced flows into EM securities even as they become more mainstream.

Consequently, the investor base for EM investments has evolved from short-term “footloose” players to longer-term stakeholders. Although fast money and proprietary desk accounts remain active, they no longer contribute to the bulk of market demand. Instead, a buildup of institutional interest—as evidenced by strategic allocations to EM by central banks and sovereign wealth funds around the world—has strengthened the foundational base of investor demand. The upshot is that broader acceptance has created a virtuous cycle of demand-supply dynamics of EM debt. Consequently, EM indices have witnessed profound changes over the last three decades.

Diversity as a Hallmark

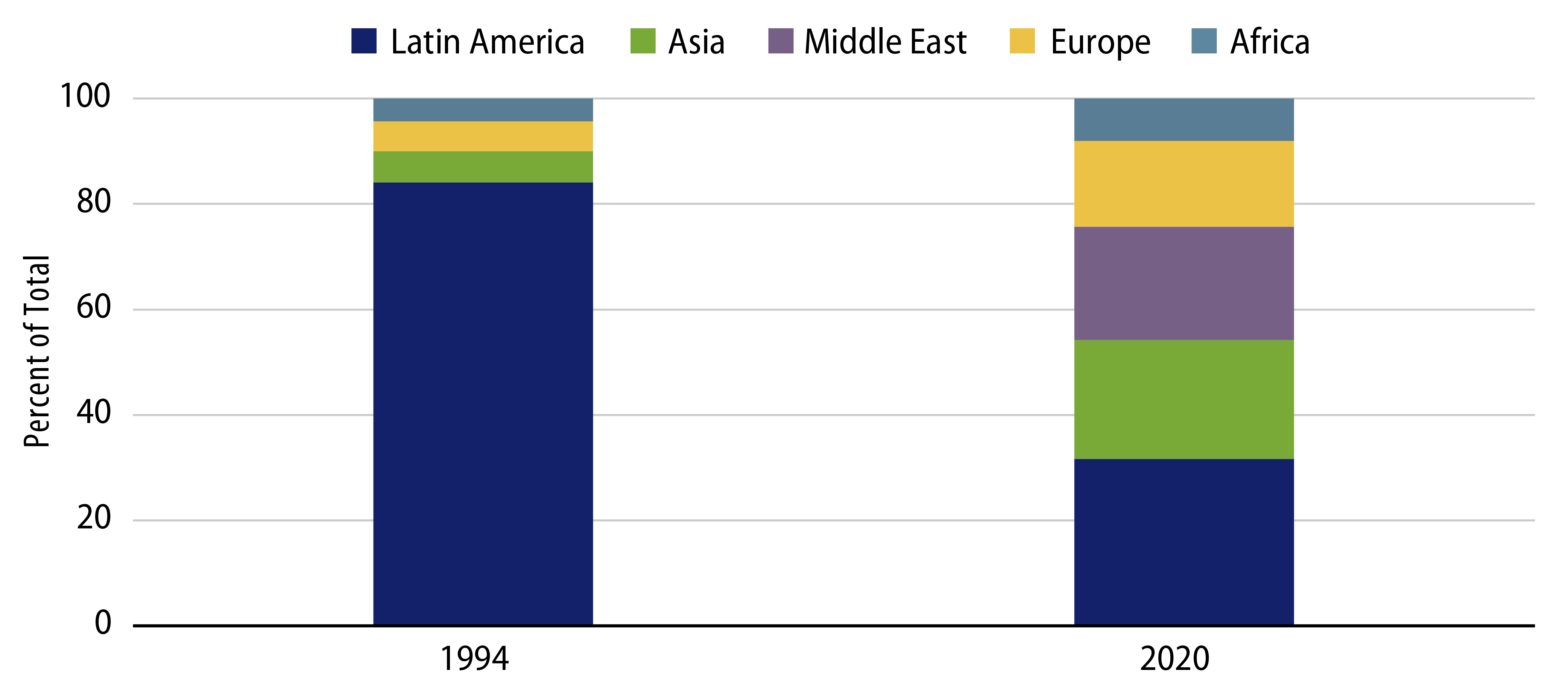

The menu of countries in the Emerging Markets Bond Index Global (EMBIG) currently stands at 74, a contrast to just eight in the precursor Emerging Markets Bond Index (EMBI) in the mid-1990s. Notably, the geographical spread of sovereign issuers has now become more global. Latin America, while historically the most dominant region, has seen its EMBIG weight slashed by more than half, to 31% presently from a high of 85% in mid-1994 (Exhibit 1). Over the same period, the EMBIG share of oil-producing Gulf countries rose from virtually zero to more than one-fifth. It might surprise some that today only two countries in Latin America—Mexico and Brazil—make it into the top-10 league table of market cap.

Historically, market access to international financing was confined to central governments and state-owned enterprises. With the establishment of EM sovereign yield curves, the spectrum of issuers broadened out to include corporates. Their arrival reflects a confluence of factors unique to EM: rapid economic growth, underdeveloped financial infrastructure and funding flexibility needs. Initially led by large investment-grade issuers, investor appetite for yield has galvanized debt issuance by high-yield companies. Over the past 15 years, the share of speculative-grade credits has more than doubled to 37% in the Corporate Emerging Market Bond Index Broad (CEMBI Broad).

As financing needs grew amid economic expansion, product innovation led to the advent of new regional indices. This is perhaps most striking in the development of the JPMorgan Asia Credit Index (JACI), comprising USD-denominated bonds issued by governments, quasi-sovereigns and corporates in 15 countries. Its market cap has grown exponentially to $1.2 trillion currently, from less than $50 billion in 2000. Against a backdrop of excess savings and low rates, Asian credits appeal to yield-hungry high-net-worth investors with familiarity of regional issuers. (This is sometimes referred to as the “home country (region) bias.”) Indeed, private placements of new bond issues which are aimed exclusively at non-US investors have become a common feature in recent years.

Different Strokes for Different Folks

It should have become clear by now that EM debt, as an asset class, is anything but monolithic. To be sure, the array of benchmarks is a well-founded attempt to capture the distinctive attributes of new subsets. Nonetheless, their categorizations may not adequately reflect an ongoing proliferation of new products, and can at times even appear problematic.1

For this reason, Western Asset believes that, while standardized off-the-shelf funds will continue to have their place, customization in EM investing will become increasingly the norm for strategic investors going forward.

For insurance companies, we view USD-denominated EM debt in a post-pandemic world as a “must have” strategic allocation with regard to their income, total return and capital needs.

By extension, for pension funds with liability management needs, a mix-and-match approach to the various EM subsets can help enhance optimization in asset allocation, thereby achieving value and diversification.

For individual investors looking to extract front-end carry, fixed maturity portfolios (FMPs) serve to achieve yield targets without giving up liquidity and diversification. Western Asset’s active management of FMPs focuses on capital preservation and income maintenance, while at the same time seeks to minimize credit and reinvestment risk.

Local currency securities issued by Aaa/AAA rated supranationals provide an innovative way for institutions that are subject to the Solvency II regime to “have their cake and eat it too.” There is a carve-out for select supranational issuers, which are not subject to spread risk charges.

Regarding the incorporation of ESG factors, our research analysts have always adopted a holistic approach, complementing quantitative projections with a contextual understanding of politics, institutions and society. The ability to implement these “stewardship” policies will determine growth trajectories, and hence their long-term creditworthiness.

Some investors are eschewing benchmarks altogether, preferring a total return approach that focuses on rotation of EM subsets in lockstep with market cycles.

À la Carte Instead of a Set Menu

First-time dim sum diners may delight in the staple dishes, and yet be turned off by the more exotic ones. On the other hand, there are those who seek culinary adventures with fusion recipes, having already tried the run-of-the-mill options. Therefore, as a cuisine, dim sum is rarely served as a prescribed set course.

Likewise, for EM, we are not fans of an index-based, wholesale approach to the asset class. Surging inflows to passively managed strategies can lead to an environment where a rising tide lifts all boats. Indeed, this is one of several past trappings of EM investing. Market gains as a result of technical flows into structurally weak countries can lead to an illusion of macro prowess and diminish the incentive for reforms. At worst, such flows represent passive investors’ tacit sponsorship for poor governance.

As the drivers of world growth become more balanced between EM and DM, we view the healthy appetite for EM as a secular trend, especially since it remains systematically under-allocated. Our investment discipline aims to deliver steady risk-adjusted returns over a full business cycle, based on our convictions in fundamental value and diversified strategies. This approach, we believe, should help achieve the desired long-term objective of “touching the heart” of EM debt.

1One such example is the treatment of securities issued by Aaa/AAA rated Temasek, a sovereign wealth fund that is wholly owned by the government of Singapore. The Temasek securities are included in JACI, but excluded from EMBIG and CEMBI Broad.