Are We at a Turning Point for Monetary Policy?

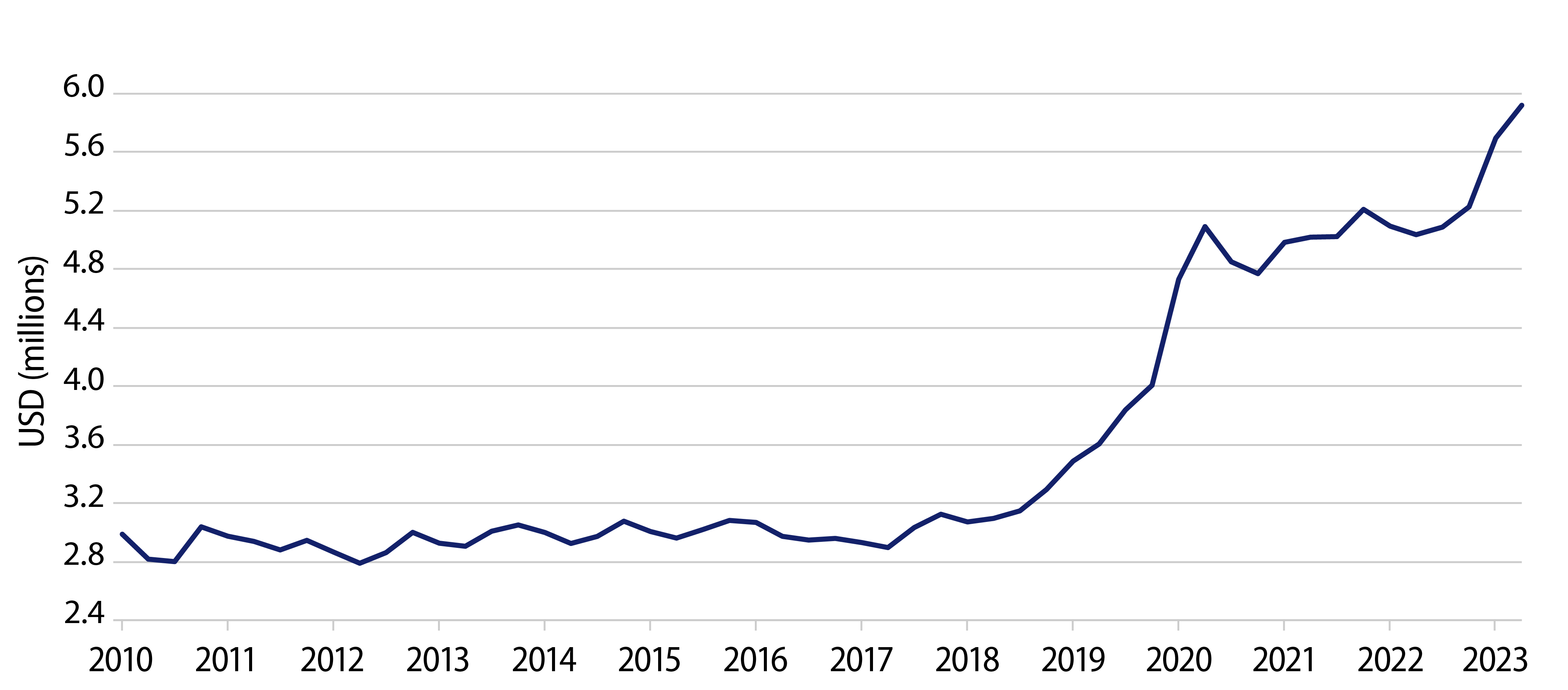

To combat inflation, monetary policy has been on a tightening upswing over the last couple of years. After the fastest and steepest pace of rates hikes in history, an inverted yield curve has done its job by attracting capital into cash (Exhibit 1) and away from investments further out the risk spectrum. If monetary policy is now at a turning point as markets believe, could this be an opportune time to take a step out the risk spectrum and lock in those higher yields?

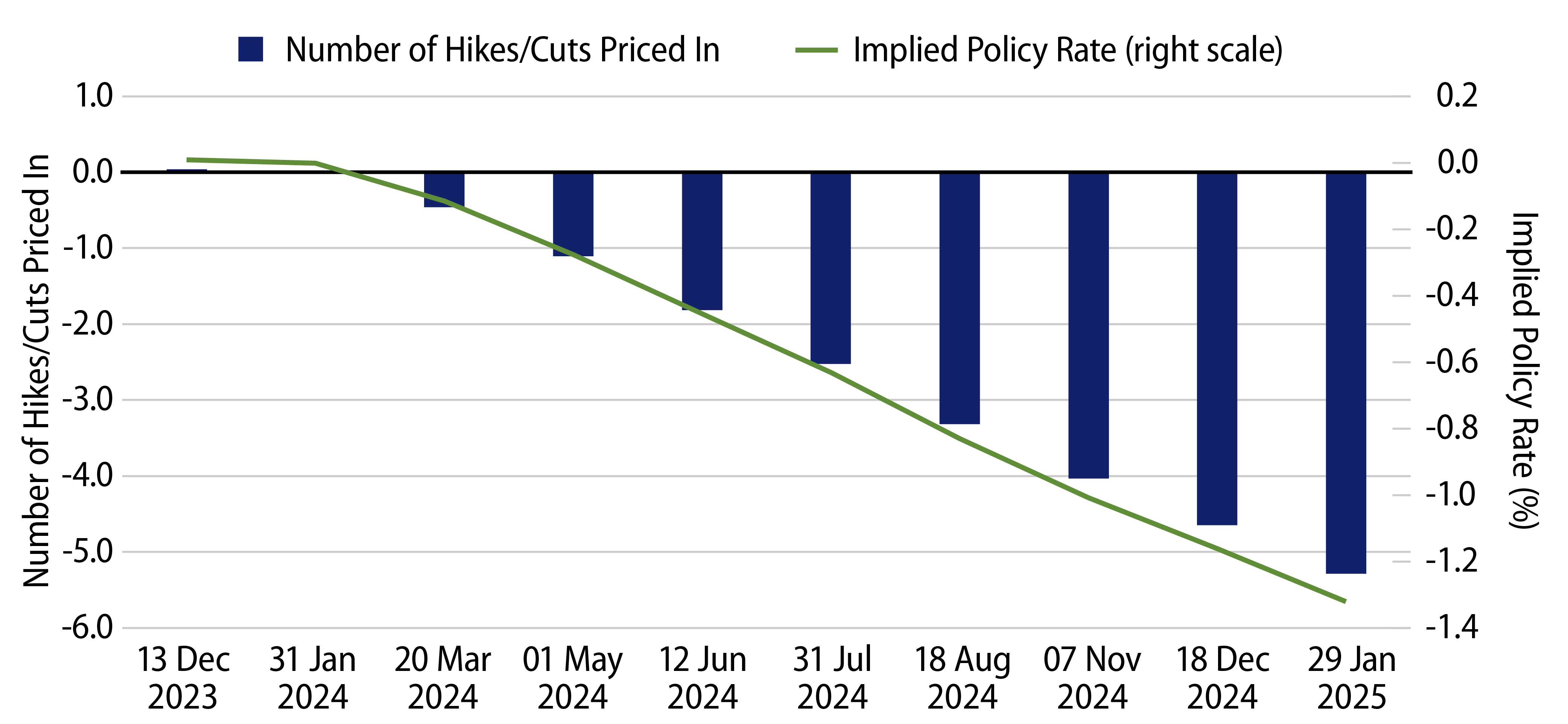

Inflation is on the decline and clearly approaching the Fed’s comfort zone, while at the same time the US economy is projected to cool from Q3’s blistering pace. As a result, over the past few weeks market expectations for Fed policy have shifted from pricing in the chance of another hike in 2023 to now bringing forward expectations of a rate cut in 2024 by a few months (Exhibit 2).

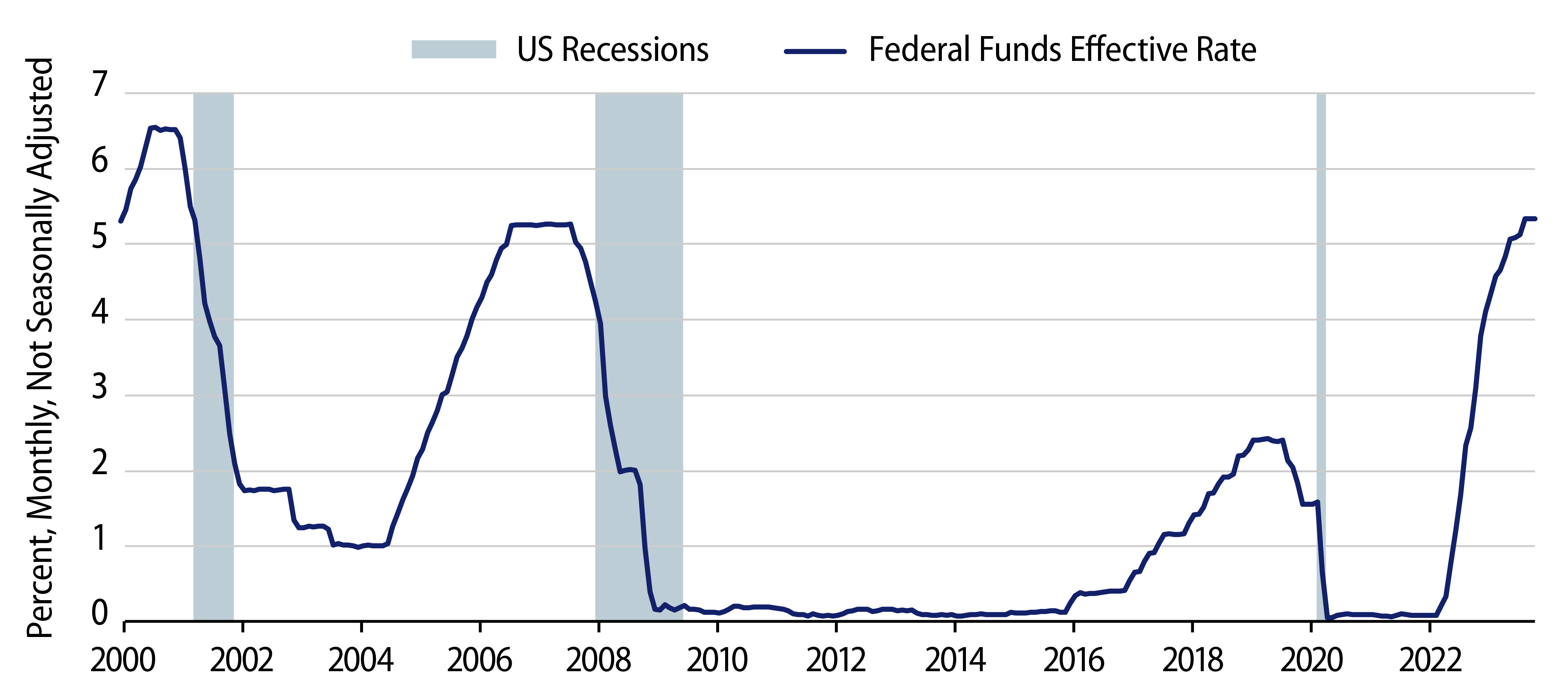

Recent history suggests market expectations may be in in the right vicinity. Monetary policy works with long and variable lags but eventually hiking cycles have almost always led to a recession (the ’94-’95 experience being the lone exception). When looking at the last three rate hike cycles, the average time the Fed has been able to maintain its highest level of policy rates has been around nine months (Exhibit 3). The last fed funds rate hike was in late July 2023 and moving nine months out from then would put us in the spring of 2024. Should market expectations play out and the Fed begin to cut policy rates sometime next year, the attractive ultra-short yields currently enjoyed by money market fund (MMF) investors will begin to dissipate.

Locking in Attractive Yields

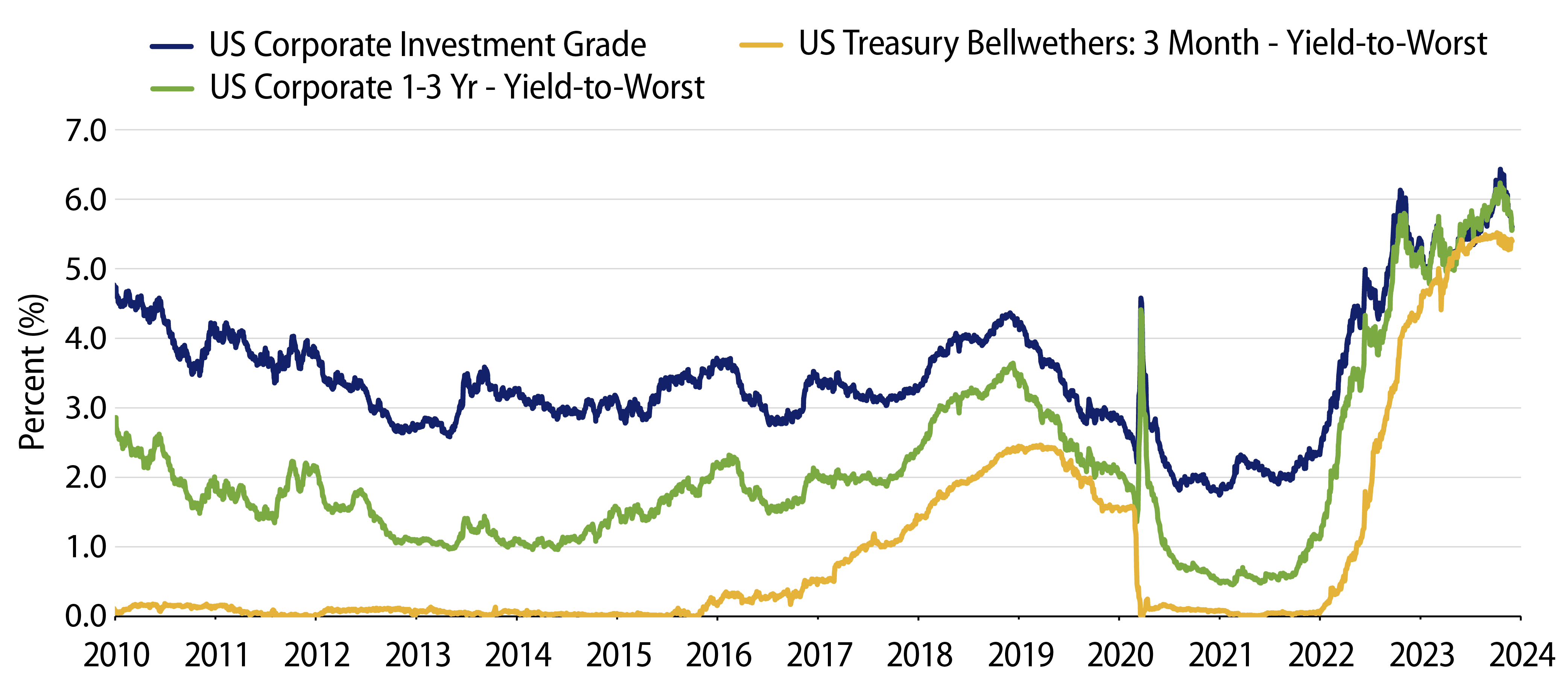

Money market fund yields will fall if and when the Fed cuts again, but investors can lock in attractive yields for at least a little while longer by taking two small steps out the risk spectrum into short-maturity high-quality corporate bonds. When compared to cash the first step out is on the maturity spectrum. Corporate bond yields in general are back to levels not seen since the immediate aftermath of the global financial crisis but the inverted Treasury yield curve has allowed short (1- to 3-year maturity) corporate yields to now rival those of longer-dated bonds (Exhibit 4) with a fraction of the interest-rate risk.

The other step out is from a fundamental credit perspective. While investment-grade corporate bonds do carry more credit risk than money market funds, the overall sector has remained resilient. Balance sheets are solid and coming off a strong starting point as corporate managements in general have remained relatively conservative in Covid’s aftermath given the overabundance of macro crosswinds. Like homeowners who refinanced their mortgages a couple of years back, corporate managements also used the low-rate environment of the Covid era to issue low coupon debt and better term out their debt profiles. The sector has little debt that needs to be refinanced over the next couple of years—in fact, less than 10% of the debt stack of the Bloomberg US Corporate index matures before the end of 2025. Consequently, rising interest expense is not an immediate concern for these investment-grade companies.

From an income-statement perspective, top-line sales have remained positive as firms were able to pass on inflationary pressures to consumers. The widely expected earnings recession of 2023 never materialized. Overall economic growth is expected to decelerate, but we believe that investment-grade companies are well positioned to weather a slowdown.

As the old saying goes, timing is everything. It may be impossible to know the very best moment to move away from cash, but after being painfully repriced over the last two years, fixed-income yields are now attractive up and down the maturity and quality spectrum. As an example of the opportunities available, the Bloomberg US Corporate 1-3 Year Index (corporate bonds with maturities between 1 and 3 years) was yielding 5.57% as of November 30, 2023. This is an additional 17 bps versus the 5.40% currently offered by 3-month Treasury bills—the differential was more than 50 bps in late-November just days before Fed Governor Waller’s “Something Appears to Be Giving” speech on November 28, comments that the market took as a dovish pivot from this widely regarded hawk—and almost 90 bps more than the 4.70% yield on a 2-year Treasury STRIP. The 2-year Treasury STRIP is a rough proxy for annualized returns of the risk-free asset over the next two years (as this STRIP yield incorporates market-implied future rates moves). With monetary policy widely expected to break from its tightening bias, now may be an opportune time to lock in attractive yields without incurring much more risk.